Cinesite sets loose a swarm of animated CG zombies into a photoreal Philadelphia cityscape in ‘World War Z’, wreaking havoc in the streets.

WORLD WAR Z: Between Two Worlds |

|

Part 2 of Digital Media World's two-part feature on the VFX of 'World War Z' |

|

Cinesite VFX supervisor Matt Johnson was one of the first people involved in preproduction on ‘World War Z’ in April 2011, from preproduction throughout the shoot period. The story begins in Philadelphia, but the only photography actually captured there was undertaken by Matt and visual effects photographer Aviv Yaron during a comprehensive photo shoot. The action seen in Philadelphia was in fact shot in Glasgow, Scotland. However, because discussions in pre-production had indicated the darker, moody 1970s thrillers as reference for the film’s looks, Cinesite’s work needed a naturalistic feel to fit into that style, matching the DP’s handheld camera work. Therefore, an intensely real approach to the environment became a major focus for the Cinesite team. |

|

Street Canyons“We put a huge effort into absolutely invisibly turning Glasgow into Philadelphia,” Matt said. “Glasgow actually works very well for the first two stories, immediately surrounding the actors during the shoot. Historically the two cities’ architectural styles have a lot in common, as their trade and finance developed in around the same era. But above street level, the differences are more obvious. We needed to create those steel and glass ‘canyons’ that Philadelphia’s more recent architecture has created in its streets.” When Matt and Aviv arrived in Philadelphia after the shoot in Glasgow, Matt had to think ahead to post production and devise a way of capturing shots that could be used to blend the locations together. He researched which buildings in Philadelphia were the most distinctive, such as Comcast Tower, Union station and so on and incorporated these into their Glasgow-Philly mash-up. Views down the very tall canyon-like streets, showing cars stretching into the distance, were carefully balanced - above a certain height, even when close to camera, the buildings were digital. “Our primary goal was to give the environment in each completed shot the same look as photography, not a CG render, in order to avoid attracting any undue attention away from the zombies and people. For the street level traffic jam, we found a good supply of American cars, taxis and ambulances in Glasgow, which we replicated and extended along the streets, plus digital people to fill out the ranks,” said Matt. |

|

|

Doing It for Real“A lot depended on the thoroughness of our reference shoot. We went up on roofs and shot at all levels, across, sides and textures. Much earlier on we had considered a 3D build-out, but once we got to Philadelphia I decided that as long as we were there, at the target location, we might as well capture everything in-camera and go for the ‘real’ approach, only relying on digital assets for the gaps, back-ups and blending.” Tracking and match moving was an essential aspect of virtually every shot Cinesite worked on. Their decision to use real photography for environments demanded a precise fit in order to place it convincingly into the plate. “It’s one of those thankless tasks that never get noticed - until it’s been done wrong, of course, and then everyone sees it,” Matt remarked. Thomas Dyg, environments supervisor, agreed that match moving and tracking the shots were critical for his team. “Not only did we need a precise line-up of photography to the live action but we had to carry the accuracy from the foreground into the background, using the full depth of the image,” he said. “In situations where you are tracking a character, for example, into the foreground that you want the audience to watch, you focus all tracking effort at that depth, but here we were working very precisely straight through the images.” |

|

|

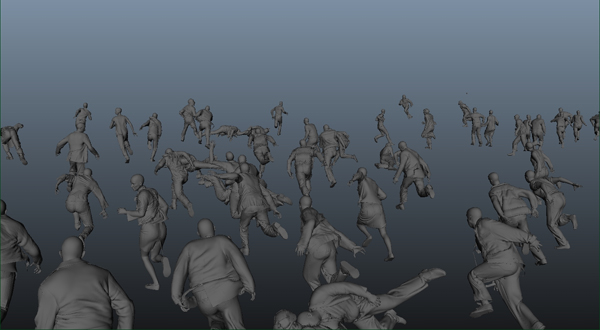

Photo MappingPerfect photorealism based on the photography became their guiding light. Thomas explained, “We could base our two main environments, Philadelphia and New Jersey, on Matt and Aviv’s reference photos. The photos were all mapped onto simple geometry allowing them to rotate and reposition the buildings, within reason, to accommodate various camera angles while keeping the photorealism of the image itself. “This was a huge benefit. While many environmental projects can be stylised to an extent in an effort to follow a story and the director’s ideas, this time the look had to be realistic to the level of a documentary. You could say we were creating unreal events – zombie attacks – happening in a real world.” For example, in a sequence shot at a large square in Glasgow where a major confrontation occurs between zombies, traffic and people, the surrounding buildings the audience sees are images of actual, recognizable buildings and elements from Philadelphia, composited into the plates to replace their Glasgow counterparts. Thomas also said that traditionally, environment teams deconstruct photography and then re-build scenes with new textures, for example, or custom shaders and lighting rigs. “Instead, we could use the photographs virtually as they were, and spend our time on art direction and accuracy that would support the VFX, animation and CG teams’ zombie work,” he said. A New ZombieIt would certainly be true that the crowds and actions of both humans and zombies are what so overwhelm the audience in nearly every sequence, starting in Philadelphia. As the street action gains momentum, the director did not want the audience to be aware that they were watching a ‘zombie movie’, but to remain unsure of what was causing the commotion – a riot perhaps, or civil unrest. The four progressive phases of zombie infection came into play at this point, as described by VFX supervisor Jessica Norman at MPC whose team defined the range of looks and behaviours [see Part 1 of this article]. Matt explained, “In Philadelphia the zombies were still in ‘phase one’, with a minimum level of physical deterioration. It gives viewers an awareness that the normal population were being chased by a different and dangerous group, and that feeling comes as much from their animation as their look. While the typical creatures of past zombie films slowly and relentlessly lumber along, these zombies have to be more immediately threatening and inescapable, rapidly advancing over large distances. Entirely new moves were called for, non-human, fast and lethal. |

|

Dance of Death“In pre-production, experimental-style dancers were engaged and succeeded in giving us truly bizarre, other-worldly performances. They worked at length with the production to refine moves such as convulsions and flinging limbs. These were captured and used both as actual motion capture and as video reference for the animators, so that we could enhance our Massive crowd simulations with incidental hand-animated actions and hero characters. “The simulations we were generating for the crowd scenes could comprise combinations of both zombie and human characters, in which the zombies were given some subtle visual clues like darker colouring to set them slightly apart. A matchmoving survey team travelled with Aviv and me on the photo shoots, accurately tracking ground planes and environmental obstacles to allow the simulation crowds to run realistically through each scene.” The way in which the zombies attack and bite became a particular focus both for Cinesite’s animation and CG teams. It was important to get the look and moves right because their bite was their means of taking down and infecting their victims – and surviving. When seeking reference, the animators looked first at football and rugby tackles but noted that an unavoidable reflex makes people facing impact throw up their arms for protection, something a voracious, inhuman zombie would not do. |

|

FearlessRealising that zombies need to launch themselves teeth first into an attack, they found that the best reference were videos of some Israeli attack dogs that run and leap fearlessly, fangs bared. But they still had to transfer this action to the human-based zombie animation. “Because it wasn’t feasible to expect any live performer to do this, we had to turn to CG. This meant starting with shots of real stunt actors and then carrying out complete, full frame take-overs with a digital double for a few frames,” said Matt. “This wasn’t only a texturing, shading and lighting challenge but also involved cloth and hair simulations. Since zombies have so much in common with people, viewers would quickly notice any inaccuracies during the multiple swaps between digital and real characters that some of these sequences needed. A cloth or hair sim might require numerous passes to work with a character’s violent animations because hair and cloth had to look very realistic but not obscure the critical part of the action that was telling the story.” In some of the more violent zombie attack scenes out in the streets, digital human characters had to be built as well, to run up in front of crashing vehicles, for example. Digital takeovers were often done with rotomation – that is, rotomating the live action performance up to the point of handover to a digital double - to blend the two performances. Work on faces, such as partial replacements of zombie characteristics applied as digital makeup to enhance the actors’ looks, were especially demanding. The eyes, jawline and other details would be rotomated to project back onto the digital work for a perfect alignment. Lighting and RenderingCG Supervisor Anthony Zwartouw explained the influence of lighting and rendering on the effects in this film, and the efforts Cinesite made to upgrade their techniques. “Over the two year period we worked on the show, the pipeline team were making continuous improvements to the skin, hair and cloth shaders we used for the hero digital doubles and crowd characters,” he said. |

|

|

|

“Although Cinesite uses Renderman as its primary rendering package, the software is heavily modified to integrate it into the pipeline. For example, all Cinesite's shaders are written from scratch by our own shader writing team. The lighting pipeline team - Alex Wilkie, Joe Gaffney and Ole Gulbrandsen - and I decided early on to try to simplify our shaders to make them more efficient and intuitive for artists. We identified parameters that should be connected and merged them, which resulted in far leaner, easier to use shaders yielding better results in less time.” Energy ConservationThey also developed co-shaders enabling the artist to plug in only the attributes that are specifically needed, rather than including all of them at once, which their previous monolithic shaders had required. Furthermore, the shaders were redesigned to mimic the real world more faithfully by adopting the principle of energy conservation. “As light – that is, energy - travels from its source and hits a surface,” Anthony explained, “it's either absorbed, scattered as in diffuse or subsurface scenarios, or reflected. The sum of the reflected, scattered and the absorbed energy should equal the initial energy from the source. “In previous shaders, it was possible to have an unrealistic situation where a material is reflecting, scattering and absorbing more energy than the light source is emitting, essentially creating energy out of thin air. A key benefit of this is the time the lighting TDs time can save when balancing shaders, producing more realistic results faster. The conservation of energy also led to more realistic behaviour in arbitrary lighting situations.” |

|

|

Fully RaytracedMeanwhile, because the production extended over such a long period, not only was Cinesite making significant upgrades to the lighting pipeline for other shows such as ‘Skyfall’, led by CG supervisor Axel Akesson, but numerous updates were also emerging for RenderMan’s software. “The biggest step was adopting a fully raytraced pipeline,” Anthony said. “The updated versions of RenderMan included a far more efficient and faster raytracer than before. In light of this, we in turn embraced an almost fully raytraced pipeline that allowed artists to create more realistic images with accurate multiple bounce reflection and diffusion. “Up until then, a lot of the passes such as indirect diffuse, subsurface scattering and ambient spherical harmonics were all calculated as pre-pass point caches. The caches were complicated, time consuming to set up and often didn’t yield accurate results. A main quality slider control was adopted, which could be set between 0 and 1 to adjust the raytrace sampling in all areas, from shadows to reflections. It also culls certain computationally heavy features once the slider passes a certain point.” The accumulation of these updates has led to a more intuitive environment for the team to light in. “An artist can import an asset, add lights and achieve a far more realistic result straight away, without setting up cumbersome point cache pre-passes,” said Anthony. |

|

|

Invented CityscapeA critical sequence takes place atop a housing project tenement building as the family of lead character Gerry Lane, pursued by violent zombies, rush desperately up a stairwell to meet a rescue helicopter that will airlift them out of the city to safety. “The action was shot on a 360° green set – a potential nightmare of a VFX scenario with only a small set piece serving as the surface of the roof the actors stood on, completely surrounded by green screen. Every angle of every view you see, except the rescue helicopter craned in overhead, was digitally created,” Matt said. Photo opportunities to capture actual housing projects like this one were non-existent but, maintaining their aim to avoid disruption of the environment into the story, the team again chose to invent this cityscape entirely from real elements. Consequently, after completing their shoot in Philadelphia, Matt and Aviv flew to New York, shooting with the intention of gathering enough imagery to create the whole rooftop rescue sequence ‘for real’ – textures in particular. Instead of recreating them in CG, they used the 3D re-projection capabilities now available in Nuke. By working in this way, 3D CG could be reserved for smaller objects but the bulk of the environmental work could still rely on photography. “The building the family stand on is based on buildings shot in Harlem, New York, while the immediately adjacent ones are from the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In the distance, to keep our scene grounded in reality, we travelled to New Jersey and found a high rooftop that gave us an effective view. From there, Aviv captured 360° or 180° panoramas using a rotating camera with a digitally tiling head,” Matt said. |

|

|

Over the edge“As you can imagine, he and I spent a lot of time on the rooftops of America, shooting complete buildings at different heights to get the flat, side-on views for textures. In the end we had real, photographic components for the full environment, foreground through to the distant background, represented by the images from Harlem, Manhattan and New Jersey.” A key reason these environments had to be as realistic as they were is that the action is not completely confined to the rooftop. The zombies shot in camera were joined by CG zombies, a number of which frantically run out of the stairwell and drop off the edge, attracting viewers’ eyes out into the environment. One key shot is angled up, looking at zombies falling from the top of the building down towards the camera on the ground. This is an entirely digital shot, featuring a CG building façade, helicopter and animated digital zombies. Safe HarbourTowards the end of the film we see a flotilla of ships from the air, heading for a harbour. Matt shot the plates for the sequence from a helicopter flying off the coast of Cornwall. There was only one live action ship in these plates, a Royal Naval Reserve ship called the ‘Argus’ as it travelled from one port to Falmouth Harbour to be shot with actors on board as a part of the movie. Once the Argus was moored in Falmouth Harbour, the action on deck of about 100 real actors needed to be augmented with another 200 digital people. The existing harbour environment in the background had to be painted out, replaced and enhanced with numerous aircraft. In particular Cinesite’s team created a CG helicopter that landed and took off from the ship, a manoeuvre that would have been too dangerous to achieve with live action due to the numbers of actors on set. |

|

|

To build up a military encampment, created from a plate shot at Lulworth Cove and seen in one long shot as the camera passes overhead, still more military vehicles were needed, of course, plus many other environmental and CG refinements. Thomas Dyg described the work here. “The environment and CG teams combined forces again. The 3D artists built some simple models for the buildings and vehicles, and textured and lit them in a generic way with lighting projections and shadows. Then our matte painters gave them a weathered look and more detail,” he said. “The camera passed over the buildings vehicles and people, then a small forest and then the cove itself, constantly changing perspective. Creating a scene like this, only seen once in this long shot in which the camera progressively changes its point of view, is very different to handling the city and rooftop environments seen from multiple angles in multiple shots over time.” |

|

Stories Inside StoriesFor the very wide shots showing aerial views of Philadelphia, the team removed the real traffic from the streets and motorways and replaced the cars with CG vehicles stuck in a massive city-wide gridlock, adding smoke and explosions overhead. One such shot included not only the traffic jam but also hundreds of thousands of desperate people walking along the motorway in a mass exodus of humans. Matt commented, “I wanted to create pockets of action to fill these shots with their own drama, and humanise the mass of people walking down motorways or across the bridge among CG cars while explosions, fires and smoke rise over their heads. The audience could consider that while this movie follows the story of Brad’s family, meanwhile hundreds of other ‘movies’ are unfolding in every direction. Shots like this were what made ‘World War Z’ such a satisfying project. So much needed to be digital, but remain in the background and enhance the story invisibly.” http://www.cinesite.com |

|

Words: Adriene Hurst |