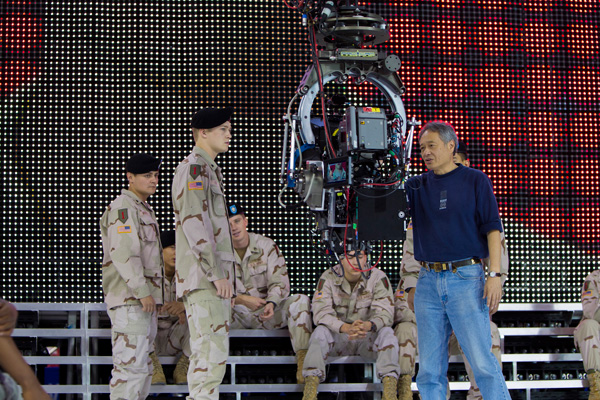

Director Ang Lee employed extreme cinematic techniques to tell the story of a soldier who returns to the USA psychologically and emotionally damaged by his time in Iraq. ‘Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk’ was shot at 120 fps in stereo 3D with high dynamic range and an extended colour gamut.

Audiences who watch the film in its native format find the result startling and uncompromising. Lacking the reassuring, artistic distance that 24fps film creates, viewers don’t look through a window into the world of the story – they are pushed into the action, bullet casings flying past their faces.

This was Ang Lee’s vision, but to make it work Sony Pictures hired Ben Gervais for experimental technical and creative support. Ben has worked as a camera assistant, broadcast engineer and post-production technician, experience that has led to his career today as a workflow consultant. On ‘Billy Lynn’ he is credited as Technical Supervisor, and worked alongside the production team at the studio.

Native Stereo at 120 fps

“We decided to shoot at 120 because that would give us the flexibility to output the range of standard formats that would be shown in theatres – we could generate 60 fps because it’s exactly half the frame rate, and 24 fps because it’s one fifth the original number of frames,” he said. Ang was also concerned that the story’s high-paced action war scenes would suffer motion stutter, causing headaches and eyestrain for viewers. Likewise, his approach was to increase the frame rate.

“Furthermore, Ang likes to push the limits of conventional cinema, and wondered how the film at 120 fps would actually look on screen. No one had ever seen footage like this before,” Ben said. “Using Christie Mirage digital projectors, and media servers from 7thSense Design, we tried it – when the lights came up after we saw it the first time, we all just sat there, stunned. We knew we had to show this to audiences because it’s remarkably different to what people are used to seeing.”

Consequently, they planned to not only shoot in native stereo at 120 fps, but to make that frame rate a key deliverable for the small number of theatres would be set up to show it. In turn, this meant they had to find a practical pipeline and workflow for post production.

Seeing How it Feels

To take advantage of that sense of immediacy in the images, Ang wanted a very realistic look that would immerse people in Billy’s experience. Ben said, “He and DoP John Toll went for a flatter, more natural look on set, because the light didn’t have to be so dramatic or contrasted.

“We used realism as a guide, knowing that the high frame rate means you see much more than you would normally see in a movie. Ang wanted to make the audience feel, as well as see, what it was really like,” he said. “’What does the heat of Iraq feel like, when it is so damn hot that the light is oppressive?’ That is something most people never experience.”

The creative vision was one thing - realising it technically was another. 120 fps with 3D in HDR, on two Sony F65 cameras, produced five times the amount of data of a standard film. Adding stereo 4K increased it to 10 times more data than conventional productions.

Ang insisted that the DI be completed in 4K 120P stereo. At that point, Ben checked with every vendor to find a system capable of playing back real-time 120 fps 4K stereo. The FilmLight Baselight X was identified as the only platform that would allow them to readily and accurately view what they had shot, and monitor how the movie was progressing during production and post.

Getting into Gear

NVIDIA GPUs were incorporated across most production stages including on-set dailies, colour, finishing and projection of 120 fps screenings. For example, during the stereo correction and visual effects stages, which were completed in The Foundry’s NUKE using the Ocula Stereo plugins, the 3D transformations and compositing were accelerated by the NVIDIA GPUs. In the conform, HDR grade and final colour grade on Baselight, the GPUs accelerated the grading, stereo correction and dual 120 fps 4K review through Christie Mirage 4K25 120 fps projectors.

Due the extreme nature of the data, a configuration with customized Colorfront software and NVIDIA GPUs had to be designed for on-set dailies to make sure they could move files as fast as possible. Taking these measures accelerated debayering, scaling, grading and colourspace conversion to transform the native colors of the camera on a regular computer monitor.

As well as needing extra power, the post team needed to perform special tasks in the conform that few other systems apart from the Baselight X could handle correctly. “For example, we frequently had to deal with frame blending because we were experimenting with running at different frame rates in the same scene," Ben said. "We were using external software to do this but it needed 50 frame handles to carry out processing. How were we going to take a completely conformed movie and expand every shot with 50 handles? Fortunately, Baselight's Timeline Sort tool could do this.”

The system's flexibility combined with power, even on the core, fundamental steps, meant the team could manipulate the Baselight to do the precise tasks they wanted it to do. Equally important, much of the viewing was also done through Baselight in their DI lab in New York.

“With a 120 frame, 4K movie in stereo, we were managing 300 to 400 terabytes of data – it’s not quick to render, it’s not quick to move over the network, it’s not quick to do anything. So, moving the playback functionality into Baselight meant that, aside from very brief caching time, we had pretty much instantaneous feedback, which made DI on the 120 frame version possible.”

Grading the Deliverables

During production three Baselight systems were used to play back dailies. These systems were packaged up and shipped out to the set in Morocco, which stands in for Iraq in the battle scenes, and then shipped back to New York for the final post, not least because of the huge amount of data accumulated – over 100TB for the final conform. It was at this point that the Baselight X was added to the project.

Colourist Adam Inglis worked on the movie for three to four weeks to set the looks for the full 120fps 4K 3D version. Adam’s colleague Marcy Robinson then joined him to finish the colour on that version and grade all the other deliverables – apart from the additional grading for Dolby Vision HDR, which was handled by Doug Delaney.

Adam said the ambition driving the project was intimidating, “The format was so integral to the look of the film that we had to grade in the full specifications - 3D, 4K and 120fps - despite the technical difficulties that came with that. The fact that I’ve been grading on Baselight since the very early days of DI - when 2D, 2K 24fps media was a challenge - made me feel more confident. There wouldn’t have been another grading system I would rather have had on such a demanding job,” Adam said.

“I only had a week with DP John Toll to define the look of the film before he had to leave for another project, and though we initially planned to just set looks for each scene and by the end of that week we had a grade on the entire film.”

Versioning

Because the production’s in-house VFX artists rendered into the Baselight directly, the team would progress through a lot of versions very quickly - as soon as the artists generated a new version, Ben’s team would have it. As technical supervisor, he wrote a significant amount of custom code to keep track of versions, EDLs and other material. “I thought keeping track was going to be very tricky,” he said.

“Then I thought, what if we put a Baselight wildcard in an EDL? I was pretty sure it was going to break the system, but we did a test and it worked. It would match all the versions of a particular VFX shot, and then ask us which one we wanted to use. Functionality like this can really simplify what you are trying to do and save time.

“Baselight X can play back both eyes at 4K 120Hz and at the same time allow creative multi-layer grading plus 3D geometry correction. Having an interactive grading system like Baselight X running at those very high, native frame rates for real-time uncompressed playback gave us a smooth creative experience. www.filmlight.ltd.uk

Words: Adriene Hurst

Images: Mary Cybulski/Sony Pictures Releasing