MPC Creative’s Mike Wigart and Dan Marsh tell what creating imagery

for VR viewing means for production and post teams, and describe their

approaches on two very different projects.

From ‘Goosebumps’ to Dream Cars, MPC Creative Makes It Virtually Real

MPC Creative, MPC’s content production arm in LA, has recently produced two diverse and exciting VR projects, based on live action photography, CG, or combinations of both. Here, Executive Producer Mike Wigart and Creative Director Dan Marsh describe what creating imagery for VR viewing means for a visual effects team, and explain their approaches from production through post.

The first project is a VR experience that travelled to theatres with the recent adventure movie ‘Goosebumps’, and the second is an all-CG VR experience produced alongside a short film, made for Faraday Future vehicle design company and launched at CES 2016. As well as camera set-ups for live action shoots, through experience the team has found that the light, 3D modelling and cameras, compositng and the grade all have to be handled in unexpected ways.

The New Frontier

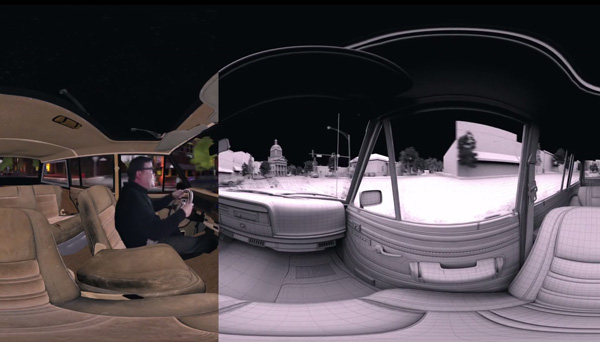

MPC’s worldwide teams joined forces with ‘Goosebumps’ movie director Rob Letterman to bring the children’s book series ‘Goosebumps’ to the screen – but not only for the film’s visual effects and title sequence. The in-theatre ‘Goosebumps’ VR Adventure experience was the special project of MPC Creative, who produced the entire project from the live-action shoot through VFX and the final grade. They also created a custom mobile app for the experience roll-out into cinemas, which runs on the Gear VR and works with special motion chairs designed by D-Box.

The team held a very specific kind of live action shoot with Rob Letterman and actor Jack Black. “VR shoots are a new frontier,” said Mike Wigart. “It was exciting for us because we were dealing with a lot of completely new techniques and could use our VFX expertise to test methods - ahead of rolling cameras.”

In the ‘Goosebumps’ movie, which Sony Pictures released in the US just before Halloween 2015, a group of kids try to save their town from the monsters of R L Stine, character and author of the books. MPC created a VR experience based on an action scene from the movie, for use with Samsung Gear VR headsets in coordination with motion chairs, custom-designed by motion systems developer D-Box. The complete, immersive ‘Goosebumps’ VR Adventure was then shown in theatres across the country over four weeks, with a very positive reception among the fans.

View the sequence as a Facebook 360° video here.

Perfect Candidate

MPC Executive Producer-VR Tim Dillon said ‘Goosebumps’ was a perfect candidate for adapting to the VR experience. “VR is intimate and immersive that transports the viewer into the space and story,” he said. “In this case, the VR Adventure places a member of the audience into a car, riding side-by-side with Jack Black at the wheel, playing R L Stine while he races through town with a giant praying mantis chasing him down. The result is a theme park-style adventure ride.”

To get there, MPC had to ensure that the realism of the piece remained intact without constraining Jack Black’s performance, the main attraction for ‘Goosebumps’ fans and what makes it fun and distinctive. Therefore, Jack and Rob Letterman needed to have the flexibility to improvise, even within such a technical production, and the handling of the shoot was critical.

Mike Wigart said, “Because the story called for our point-of-view to be fixed alongside Jack while he remains seated behind the wheel, we determined that we could shoot him as a single element or ‘slice’ of the 360-degree surrounding environment. This eliminated the need to shoot on a stereo VR rig. We then had to decide which camera set-up would give us the correct interocular distance in such tight proximity to the subject.

“Michael Mansouri at Radiant Images generously opened his doors for a camera test. We tried using a RED stereo pair on a beam splitter, but it proved to be too cumbersome. So we took a pair of Codex Action Cams, which were small enough to allow us to separate them by roughly the same distance as a pair of human eyes, and flip them to portrait mode for full body coverage.”

Environmental Lights

The way the lighting was handled was also interesting, both in terms of Jack’s performance and the resulting footage. Knowing that Jack would be the only live-action element composited into a fully CG environment, it was important that the on-set lighting mimicked the environment lighting as closely as possible.

“We worked with lighting technicians at Performance Resource Group to establish a stage lighting scenario involving three LED panels positioned front, left and just above the car,” said Mike. “We had created a previs sequence of the environment, which we projected through these panels to cast accurate source lighting and shadows on Jack. This also gave him a means of keeping track of the scene passing around him, and remaining aware of where he was in the story.”

While viewers would be expecting the town to look just like the town in the movie, re-creating it for a VR experience was not simply a matter of borrowing CG sets from the MPC Film team in Vancouver. The Praying Mantis scene from the film had been shot on location and the VFX artists had extended the sets on a shot-by-shot basis according to the camera work. But VR production doesn’t necessarily proceed as ‘shots’. The full 360° view has to be available at all times.

Nowhere to Hide

Mike said, “There aren’t many places to hide in VR. We used all the data we could get from the shoot and reconstructed an environment that could be visible in all directions for the duration of the piece. You not only see the environment at all times but also the characters, which was especially evident in animating the Mantis. As he’s constantly in the shot, we had to keyframe him the entire time.

We started by animating the car through the environment to determine a speed that was exciting but wouldn’t make you nauseous. Once we had the car’s path, we animated the Mantis action around the car, taking cues from Jack’s performance to help guide the viewer’s POV. It was a fair amount of work, but we benefited tremendously from having solid set data and the scene from the film itself as a great reference to target.”

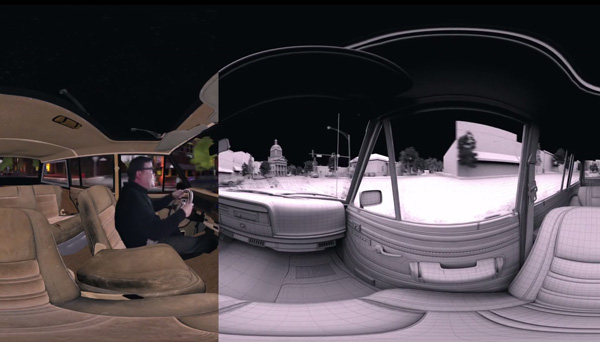

The need to composite a live action element into a 360-degree, stereo CG environment was another challenge. While a CG character like the Mantis had the advantage of being lit with an animated HDR to help sit him in the environment, for Jack, utilizing the LED panels to light him on set went a long way in this respect. “But we also captured him with two kinds of flight sensors and created a mesh that we ran through the lit environment. This gave our compositors a diffuse render to multiply into their Jack composite, which was all part of that final 10% integration that can make or break a shot - or the entire VR experience,” said Mike.

“There are no lenses to match in this case, as the experience is rendered through a 360-degree camera. Our Codex cameras shot on a Kowa 5mm, an aspherical lens with short minimum object distance that reduces distortion, but Jack's element was essentially a card placed in 3D space.”

In Motion with D-Box

The chair movement was a crucial part of the overall experience and D-Box was a creative partner on the project. The Team Lead of Motion Design at D-Box Jessy Auclair was on set with the production to witness how the shoot unfolded. Once they had a select, he custom-programmed the chair movements to their temporary animations. Mike said, “The director Rob Letterman definitely wanted to push the limits of the chair action, so Jessy turned it right up to 11. The motion code is initiated by the waveform in the audio track, so we had to be smart in our sound design to include some cues up front that the chair would recognize.”

From there, so that the chair and headset worked together, an auxiliary extension ran from the D-Box into an audio splitter with one end in the Samsung Gear VR headset and the other connected to the headphones.

As a true, full production operation, MPC Creative worked hand-in-hand with the Sony Marketing team to ensure a smooth roll out. Mike said, “We were in charge of the procurement of all equipment, we created a custom app that would run the content and we set up, loaded and QC’d the content in each Samsung phone that went out into the field. This was no small undertaking – it was far from the sexiest part of the job, but something I’m extremely proud of. Aside from a few hiccups the first day of the roll out, over 30 VR headsets and D-Box chairs operated in the field without a hitch. It felt miraculous.”

Faraday Future’s FFZERO1 Electric Dream Car

MPC Creative also produced a short film plus a VR experience of a very different type for a different audience at CES 2016. These productions highlight the performance of Faraday Future’s vehicle design platform with hints of the innovations consumers can expect from their product line in the marketplace. MPC’s work earned Faraday Future recognition for some of the hottest tech product debuts at the show.

First, the CES film is about a concept car, the FFZERO1 high-performance electric dream car, developed as the inspiration for Faraday Future’s consumer-based cars. Dan Marsh, creative director of MPC Creative who directed the FF projects, said, “Faraday Future as a brand aims for a direct connection between technology and transportation.

“The film shows a clean, simple future for cars, not only for the engineering but in the way people will use cars. We tried to make the film personal and the car feel natural in the landscape.” The Faraday Future car is engineered for the racetrack, in the very near future, but looks beautiful in its environment. Therefore, the performance is fierce but not aggressive, focussed instead on energy and ambition.

“To make the film, we shot a stand-in vehicle to achieve realistic driving performance and camera work,” said Dan. “We filmed in Malibu and at a performance racetrack, then married those locations together with some matte painting and CG to create a unique place that feels like an aspirational Nürburgring of sorts. “

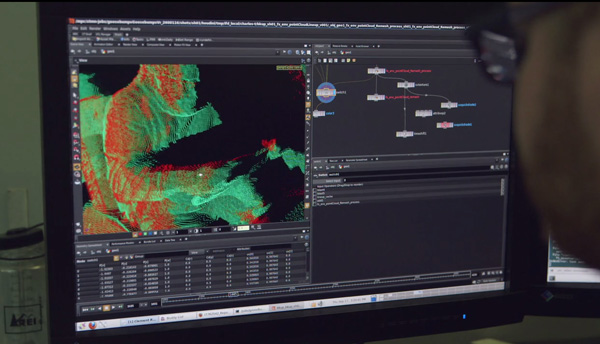

On the Track

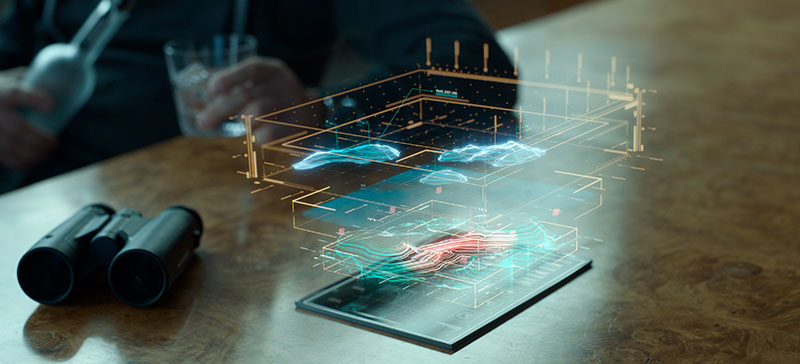

To accurately build their concept car, MPC’s artists visited Faraday Future to look at scale models and get material samples to replicate. For the stage shoot and interior shots, they had a foam model of the car seat and a steering wheel. They also had the race car data, and data for visualizing the battery platform. The modellers bridged the gaps to bring it all together, but stay on target with the look. Meanwhile, the look development artists worked with Dan and the designers, animators and riggers to allow for a transition at the end into a CG animated break-apart sequence at the end.

Dan described the shoot, which was comprised of three days divided between the race track, Malibu hills and the stage, and was carried out like a real driver’s shoot. “We shot our stand-in vehicle on the track and at Malibu using a pursuit vehicle with an arm, just as traditional driving footage would be handled. We chose a vehicle that could match the performance, but be replaced by the wider, longer FF race car,” he said.

“We had a secondary camera vehicle for POV and simulated car mounts, such as the shots viewed from the race car's wheel and the rear tail fin and launched a drone in the Malibu hills to get the aerial shots. Principal photography was captured in ARRIRAW on the ALEXA. We also used a spherical fisheye lens to capture reflection/lighting plates that would match the environment we were driving in.”

Photography at Malibu involved a few separate sections of road that they closed off for performance driving. They captured car-to-car high speed footage, as well as the drone and POV photography and VFX lighting plates.

Day for Dawn

As the film unfolds we watch the pre-sunrise progress to dawn. However, the actual shooting schedules required that many shots were handled from morning into afternoon, which meant that light was continuously changing. “Because we knew we'd be replacing the car, we always followed a ‘day-for-dawn’ style of shoot,” Dan said. “This meant looking at when and where we could see the sun, favouring certain angles and avoiding others. We painted shadows out of some shots to help, but as the car was CG, we had to light it anyway.”

“To ensure the integration of the CG was believable, we actually did the grading at the end. Creating a stylized grade like this can make matching CG incredibly difficult. So, we decided to match the CG lighting to the practical photography first, but the compositors could look through a pre-grade as they worked to give them an estimation of where the grade would end up. This let us match the CG car to the plate, decide which shots needed pre-grade lighting tweaks, and then finalize a grade at the end as if it were working with all of the practical photography.”

Speed was handled photographically. As Dan explained, certain techniques can help sell speed, but nothing circumvents the fact that the car needs to be in motion. They had a top-notch driver in the car as well as the driver and operators in the pursuit vehicle, and kept it as safe as they do on any other set - but pushed it to the limit.

Every shot in the project taken from the live-action photography retains its real camera move. Whenever possible, the stand-in car was match-moved in shots and replaced with the CG race car and when necessary, they animated on top of that to tie the story together. If literally replacing the car was too difficult for extreme close-up shots, they started with a clean plate and used the car footage as reference for the race car animation.

Mood Edit

In the first few seconds the view cuts from only a few millimetres away from the car to an aerial view of the track, to the driver’s device. The editing is quick and dramatic throughout the film but does not feel rushed, and the car is fast but the feeling is not frantic.

“Unusually for me, this was actually the least collaborative part of the project. The brief was so abstract that I just had a feeling for it in my head, so I tried a different process for this film. I created a mood edit with photography and footage, and then talked to the storyboard artist to fill in gaps. We used previs for the full-CG sections at the end to tell that story in the mood edit. Our shooting boards ended up as a mixture of that mood edit, scout photography and storyboards, and the edit turned out remarkably close to that mood edit.

Faraday Future FFZERO1 VR Experience

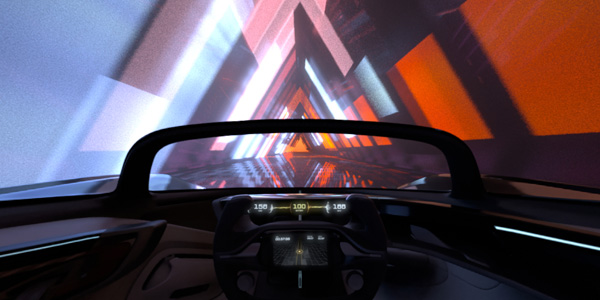

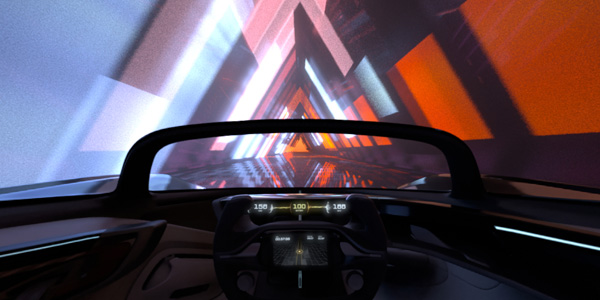

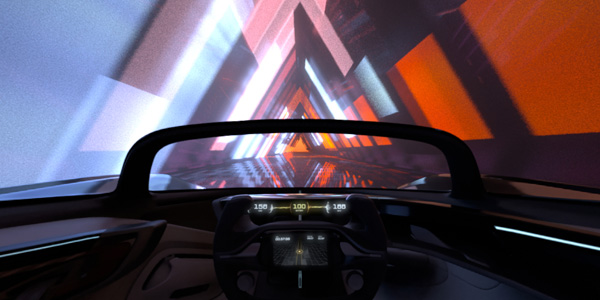

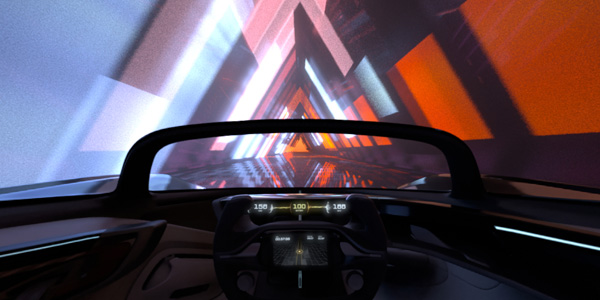

MPC Creative also produced a Faraday Future VR experience that puts the viewer in the driver’s seat, set to take the FFZERO1 on a fantasy drive through a series of abstract environments. These environments have an architectural, sculptural design and give the audience a spiritual journey as opposed to a road trip. Using Samsung’s Gear VR, attendees at CES sat in a position similar to the angled seating of the race car for their 360 tour.

“Faraday Future wanted to put viewers in the driver’s seat, but more than that they wanted to create a compelling experience that points to some of the new ideas they are focusing on,” said Director Dan Marsh at MPC Creative, who directed both the film and the VR experience. “We've seen and made a lot of car driving experiences, but without a compelling narrative the piece can be in danger of being VR for the sake of it.

“In this case, we visualised something for Faraday Future that you couldn't see otherwise. We conceived an architectural framework for the experience. Participants travel through a racetrack of sorts, but each stage takes you through a unique space. But we're also travelling fast so, like the film, we're teasing the possibilities.”

In contrast to the film, the Faraday Future VR Experience pulls the POV entirely inside the car. Dan said, “To get started, we storyboarded out a sequence, and paired that with visual reference of environments. We were starting from a blank canvas but grounded ourselves with some early inspiration and mood boards that Faraday Future shared with us. We used that to fuel a broader search and when we found forms we liked, we paired those with lighting materials or scales to communicate our ideas with the client.

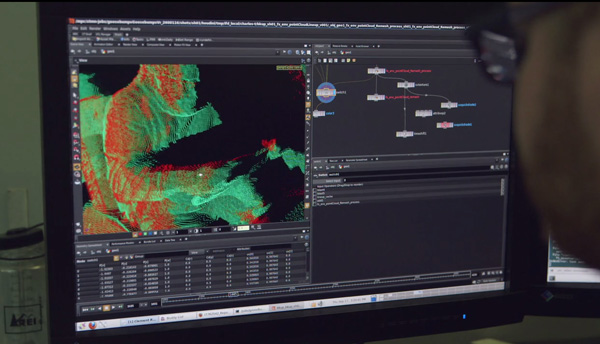

“When that was approved, we began mapping out the course the car would travel, the scale of each ‘room’ in the journey and how fast we wanted to be going. To do this, we built a 360-degree Playblast tool in Maya - which creates a preview of the animation that runs in real time and outputs much faster than a render - and played that through a live feed into an Oculus headset so that we could get a sense of scale of the different rooms and make adjustments. We could then logically set up each room into different scenes and determine which tools were right for the job. From there, the environments were modelled, textured and lit little by little.”

The Drive

Thus, while the creation process was fairly standard in many respects, the design had to be tailored to the headset experience and, just as in live-action 360° footage, nothing could be hidden out of frame. The drive was mapped out first in a 2D overhead view. From this, the team built a ‘track’ base in real world dimensions and could then make tweaks to the speed of the car and scale of the rooms to give a flow to the piece. On this point, their goal was based less in pure reality than in the sensational.

“For example, because establishing a sense of speed depended entirely on the environment in which we were travelling, we could use the scale of the spaces and their design, such as vertical structures near or far from the viewer, to give nice visual cues for slow or fast movement. In VR with just a headset, you have sight and sound but no other physical senses tied to the piece - it’s a little like being in an elevator.”

The project was delivered as an app packaged into phones for the exhibition visitors to use, which works similarly to many others displaying 360 content. The video is rendered as a lat-long image, distorted in the way a map of the globe gets flattened out into a 2D map, so that certain parts are stretched and squished. When the viewers put on their headsets, this image is effectively corrected once it is wrapped back into a sphere that surrounds them.

Interestingly, Dan noted, “Though in the end we delivered the entire app installed on devices, the visual deliverable is in fact a high-res h.264 compressed video file. Unfortunately, the current specs of the Gear VR only allows for smooth playback up to resolutions of 4K, but that doesn't mean 4K in the viewers’ eyes. It means that the whole spherical image is 4K wide by 2K tall. So the viewer is actually only seeing a small window of that 4K image, and obviously that will improve rapidly over time. www.moving-picture.com

MPC Creative’s Mike Wigart and Dan Marsh tell what creating imagery

for VR viewing means for production and post teams, and describe their

approaches on two very different projects.

From ‘Goosebumps’ to Dream Cars, MPC Creative Makes It Virtually Real

MPC Creative, MPC’s content production arm in LA, has recently produced two diverse and exciting VR projects, based on live action photography, CG, or combinations of both. Here, Executive Producer Mike Wigart and Creative Director Dan Marsh describe what creating imagery for VR viewing means for a visual effects team, and explain their approaches from production through post.

The first project is a VR experience that travelled to theatres with the recent adventure movie ‘Goosebumps’, and the second is an all-CG VR experience produced alongside a short film, made for Faraday Future vehicle design company and launched at CES 2016. As well as camera set-ups for live action shoots, through experience the team has found that the light, 3D modelling and cameras, compositng and the grade all have to be handled in unexpected ways.

The New Frontier

MPC’s worldwide teams joined forces with ‘Goosebumps’ movie director Rob Letterman to bring the children’s book series ‘Goosebumps’ to the screen – but not only for the film’s visual effects and title sequence. The in-theatre ‘Goosebumps’ VR Adventure experience was the special project of MPC Creative, who produced the entire project from the live-action shoot through VFX and the final grade. They also created a custom mobile app for the experience roll-out into cinemas, which runs on the Gear VR and works with special motion chairs designed by D-Box.

The team held a very specific kind of live action shoot with Rob Letterman and actor Jack Black. “VR shoots are a new frontier,” said Mike Wigart. “It was exciting for us because we were dealing with a lot of completely new techniques and could use our VFX expertise to test methods - ahead of rolling cameras.”

In the ‘Goosebumps’ movie, which Sony Pictures released in the US just before Halloween 2015, a group of kids try to save their town from the monsters of R L Stine, character and author of the books. MPC created a VR experience based on an action scene from the movie, for use with Samsung Gear VR headsets in coordination with motion chairs, custom-designed by motion systems developer D-Box. The complete, immersive ‘Goosebumps’ VR Adventure was then shown in theatres across the country over four weeks, with a very positive reception among the fans.

View the sequence as a Facebook 360° video here.

Perfect Candidate

MPC Executive Producer-VR Tim Dillon said ‘Goosebumps’ was a perfect candidate for adapting to the VR experience. “VR is intimate and immersive that transports the viewer into the space and story,” he said. “In this case, the VR Adventure places a member of the audience into a car, riding side-by-side with Jack Black at the wheel, playing R L Stine while he races through town with a giant praying mantis chasing him down. The result is a theme park-style adventure ride.”

To get there, MPC had to ensure that the realism of the piece remained intact without constraining Jack Black’s performance, the main attraction for ‘Goosebumps’ fans and what makes it fun and distinctive. Therefore, Jack and Rob Letterman needed to have the flexibility to improvise, even within such a technical production, and the handling of the shoot was critical.

Mike Wigart said, “Because the story called for our point-of-view to be fixed alongside Jack while he remains seated behind the wheel, we determined that we could shoot him as a single element or ‘slice’ of the 360-degree surrounding environment. This eliminated the need to shoot on a stereo VR rig. We then had to decide which camera set-up would give us the correct interocular distance in such tight proximity to the subject.

“Michael Mansouri at Radiant Images generously opened his doors for a camera test. We tried using a RED stereo pair on a beam splitter, but it proved to be too cumbersome. So we took a pair of Codex Action Cams, which were small enough to allow us to separate them by roughly the same distance as a pair of human eyes, and flip them to portrait mode for full body coverage.”

Environmental Lights

The way the lighting was handled was also interesting, both in terms of Jack’s performance and the resulting footage. Knowing that Jack would be the only live-action element composited into a fully CG environment, it was important that the on-set lighting mimicked the environment lighting as closely as possible.

“We worked with lighting technicians at Performance Resource Group to establish a stage lighting scenario involving three LED panels positioned front, left and just above the car,” said Mike. “We had created a previs sequence of the environment, which we projected through these panels to cast accurate source lighting and shadows on Jack. This also gave him a means of keeping track of the scene passing around him, and remaining aware of where he was in the story.”

While viewers would be expecting the town to look just like the town in the movie, re-creating it for a VR experience was not simply a matter of borrowing CG sets from the MPC Film team in Vancouver. The Praying Mantis scene from the film had been shot on location and the VFX artists had extended the sets on a shot-by-shot basis according to the camera work. But VR production doesn’t necessarily proceed as ‘shots’. The full 360° view has to be available at all times.

Nowhere to Hide

Mike said, “There aren’t many places to hide in VR. We used all the data we could get from the shoot and reconstructed an environment that could be visible in all directions for the duration of the piece. You not only see the environment at all times but also the characters, which was especially evident in animating the Mantis. As he’s constantly in the shot, we had to keyframe him the entire time.

We started by animating the car through the environment to determine a speed that was exciting but wouldn’t make you nauseous. Once we had the car’s path, we animated the Mantis action around the car, taking cues from Jack’s performance to help guide the viewer’s POV. It was a fair amount of work, but we benefited tremendously from having solid set data and the scene from the film itself as a great reference to target.”

The need to composite a live action element into a 360-degree, stereo CG environment was another challenge. While a CG character like the Mantis had the advantage of being lit with an animated HDR to help sit him in the environment, for Jack, utilizing the LED panels to light him on set went a long way in this respect. “But we also captured him with two kinds of flight sensors and created a mesh that we ran through the lit environment. This gave our compositors a diffuse render to multiply into their Jack composite, which was all part of that final 10% integration that can make or break a shot - or the entire VR experience,” said Mike.

“There are no lenses to match in this case, as the experience is rendered through a 360-degree camera. Our Codex cameras shot on a Kowa 5mm, an aspherical lens with short minimum object distance that reduces distortion, but Jack's element was essentially a card placed in 3D space.”

In Motion with D-Box

The chair movement was a crucial part of the overall experience and D-Box was a creative partner on the project. The Team Lead of Motion Design at D-Box Jessy Auclair was on set with the production to witness how the shoot unfolded. Once they had a select, he custom-programmed the chair movements to their temporary animations. Mike said, “The director Rob Letterman definitely wanted to push the limits of the chair action, so Jessy turned it right up to 11. The motion code is initiated by the waveform in the audio track, so we had to be smart in our sound design to include some cues up front that the chair would recognize.”

From there, so that the chair and headset worked together, an auxiliary extension ran from the D-Box into an audio splitter with one end in the Samsung Gear VR headset and the other connected to the headphones.

As a true, full production operation, MPC Creative worked hand-in-hand with the Sony Marketing team to ensure a smooth roll out. Mike said, “We were in charge of the procurement of all equipment, we created a custom app that would run the content and we set up, loaded and QC’d the content in each Samsung phone that went out into the field. This was no small undertaking – it was far from the sexiest part of the job, but something I’m extremely proud of. Aside from a few hiccups the first day of the roll out, over 30 VR headsets and D-Box chairs operated in the field without a hitch. It felt miraculous.”

Faraday Future’s FFZERO1 Electric Dream Car

MPC Creative also produced a short film plus a VR experience of a very different type for a different audience at CES 2016. These productions highlight the performance of Faraday Future’s vehicle design platform with hints of the innovations consumers can expect from their product line in the marketplace. MPC’s work earned Faraday Future recognition for some of the hottest tech product debuts at the show.

First, the CES film is about a concept car, the FFZERO1 high-performance electric dream car, developed as the inspiration for Faraday Future’s consumer-based cars. Dan Marsh, creative director of MPC Creative who directed the FF projects, said, “Faraday Future as a brand aims for a direct connection between technology and transportation.

“The film shows a clean, simple future for cars, not only for the engineering but in the way people will use cars. We tried to make the film personal and the car feel natural in the landscape.” The Faraday Future car is engineered for the racetrack, in the very near future, but looks beautiful in its environment. Therefore, the performance is fierce but not aggressive, focussed instead on energy and ambition.

{media load=media,id=134,width=675,align=left,display=inline}

“To make the film, we shot a stand-in vehicle to achieve realistic driving performance and camera work,” said Dan. “We filmed in Malibu and at a performance racetrack, then married those locations together with some matte painting and CG to create a unique place that feels like an aspirational Nürburgring of sorts. “

On the Track

To accurately build their concept car, MPC’s artists visited Faraday Future to look at scale models and get material samples to replicate. For the stage shoot and interior shots, they had a foam model of the car seat and a steering wheel. They also had the race car data, and data for visualizing the battery platform. The modellers bridged the gaps to bring it all together, but stay on target with the look. Meanwhile, the look development artists worked with Dan and the designers, animators and riggers to allow for a transition at the end into a CG animated break-apart sequence at the end.

Dan described the shoot, which was comprised of three days divided between the race track, Malibu hills and the stage, and was carried out like a real driver’s shoot. “We shot our stand-in vehicle on the track and at Malibu using a pursuit vehicle with an arm, just as traditional driving footage would be handled. We chose a vehicle that could match the performance, but be replaced by the wider, longer FF race car,” he said.

“We had a secondary camera vehicle for POV and simulated car mounts, such as the shots viewed from the race car's wheel and the rear tail fin and launched a drone in the Malibu hills to get the aerial shots. Principal photography was captured in ARRIRAW on the ALEXA. We also used a spherical fisheye lens to capture reflection/lighting plates that would match the environment we were driving in.”

Photography at Malibu involved a few separate sections of road that they closed off for performance driving. They captured car-to-car high speed footage, as well as the drone and POV photography and VFX lighting plates.

Day for Dawn

As the film unfolds we watch the pre-sunrise progress to dawn. However, the actual shooting schedules required that many shots were handled from morning into afternoon, which meant that light was continuously changing. “Because we knew we'd be replacing the car, we always followed a ‘day-for-dawn’ style of shoot,” Dan said. “This meant looking at when and where we could see the sun, favouring certain angles and avoiding others. We painted shadows out of some shots to help, but as the car was CG, we had to light it anyway.”

“To ensure the integration of the CG was believable, we actually did the grading at the end. Creating a stylized grade like this can make matching CG incredibly difficult. So, we decided to match the CG lighting to the practical photography first, but the compositors could look through a pre-grade as they worked to give them an estimation of where the grade would end up. This let us match the CG car to the plate, decide which shots needed pre-grade lighting tweaks, and then finalize a grade at the end as if it were working with all of the practical photography.”

Speed was handled photographically. As Dan explained, certain techniques can help sell speed, but nothing circumvents the fact that the car needs to be in motion. They had a top-notch driver in the car as well as the driver and operators in the pursuit vehicle, and kept it as safe as they do on any other set - but pushed it to the limit.

Every shot in the project taken from the live-action photography retains its real camera move. Whenever possible, the stand-in car was match-moved in shots and replaced with the CG race car and when necessary, they animated on top of that to tie the story together. If literally replacing the car was too difficult for extreme close-up shots, they started with a clean plate and used the car footage as reference for the race car animation.

Mood Edit

In the first few seconds the view cuts from only a few millimetres away from the car to an aerial view of the track, to the driver’s device. The editing is quick and dramatic throughout the film but does not feel rushed, and the car is fast but the feeling is not frantic.

“Unusually for me, this was actually the least collaborative part of the project. The brief was so abstract that I just had a feeling for it in my head, so I tried a different process for this film. I created a mood edit with photography and footage, and then talked to the storyboard artist to fill in gaps. We used previs for the full-CG sections at the end to tell that story in the mood edit. Our shooting boards ended up as a mixture of that mood edit, scout photography and storyboards, and the edit turned out remarkably close to that mood edit.

Faraday Future FFZERO1 VR Experience

MPC Creative also produced a Faraday Future VR experience that puts the viewer in the driver’s seat, set to take the FFZERO1 on a fantasy drive through a series of abstract environments. These environments have an architectural, sculptural design and give the audience a spiritual journey as opposed to a road trip. Using Samsung’s Gear VR, attendees at CES sat in a position similar to the angled seating of the race car for their 360 tour.

“Faraday Future wanted to put viewers in the driver’s seat, but more than that they wanted to create a compelling experience that points to some of the new ideas they are focusing on,” said Director Dan Marsh at MPC Creative, who directed both the film and the VR experience. “We've seen and made a lot of car driving experiences, but without a compelling narrative the piece can be in danger of being VR for the sake of it.

“In this case, we visualised something for Faraday Future that you couldn't see otherwise. We conceived an architectural framework for the experience. Participants travel through a racetrack of sorts, but each stage takes you through a unique space. But we're also travelling fast so, like the film, we're teasing the possibilities.”

{media load=media,id=135,width=675,align=left,display=inline}

In contrast to the film, the Faraday Future VR Experience pulls the POV entirely inside the car. Dan said, “To get started, we storyboarded out a sequence, and paired that with visual reference of environments. We were starting from a blank canvas but grounded ourselves with some early inspiration and mood boards that Faraday Future shared with us. We used that to fuel a broader search and when we found forms we liked, we paired those with lighting materials or scales to communicate our ideas with the client.

“When that was approved, we began mapping out the course the car would travel, the scale of each ‘room’ in the journey and how fast we wanted to be going. To do this, we built a 360-degree Playblast tool in Maya - which creates a preview of the animation that runs in real time and outputs much faster than a render - and played that through a live feed into an Oculus headset so that we could get a sense of scale of the different rooms and make adjustments. We could then logically set up each room into different scenes and determine which tools were right for the job. From there, the environments were modelled, textured and lit little by little.”

The Drive

Thus, while the creation process was fairly standard in many respects, the design had to be tailored to the headset experience and, just as in live-action 360° footage, nothing could be hidden out of frame. The drive was mapped out first in a 2D overhead view. From this, the team built a ‘track’ base in real world dimensions and could then make tweaks to the speed of the car and scale of the rooms to give a flow to the piece. On this point, their goal was based less in pure reality than in the sensational.

“For example, because establishing a sense of speed depended entirely on the environment in which we were travelling, we could use the scale of the spaces and their design, such as vertical structures near or far from the viewer, to give nice visual cues for slow or fast movement. In VR with just a headset, you have sight and sound but no other physical senses tied to the piece - it’s a little like being in an elevator.”

The project was delivered as an app packaged into phones for the exhibition visitors to use, which works similarly to many others displaying 360 content. The video is rendered as a lat-long image, distorted in the way a map of the globe gets flattened out into a 2D map, so that certain parts are stretched and squished. When the viewers put on their headsets, this image is effectively corrected once it is wrapped back into a sphere that surrounds them.

Interestingly, Dan noted, “Though in the end we delivered the entire app installed on devices, the visual deliverable is in fact a high-res h.264 compressed video file. Unfortunately, the current specs of the Gear VR only allows for smooth playback up to resolutions of 4K, but that doesn't mean 4K in the viewers’ eyes. It means that the whole spherical image is 4K wide by 2K tall. So the viewer is actually only seeing a small window of that 4K image, and obviously that will improve rapidly over time. www.moving-picture.com