Glassworks in Barcelona created two beautiful animations telling powerful stories-inside-a-story to support the film ‘A Monster Calls’. The animations are based on fantastic tales the young protagonist Conor O’Malley invents and illustrates, while his own real-life drama unfolds around him.

In the novel that the film is based on, the tales are essential to understanding the conflicts Conor experiences, and therefore the animations are also designed as a core part of the film. To varying degrees, depending on what is happening, they also mix reality with fantasy, producing a fascinating convergence that reveals his true thoughts.

Defining a Style

Glassworks created the animations from scratch. The creative direction came from another Spanish company, Headless Productions, also in Barcelona, whose animation director Adrian Garcia had worked with Glasswork’s head of 3D and leader of this project, Javier Verdugo, on earlier projects. Although Headless Productions had created storyboards, defined major themes and assembled various background materials, the project had yet to get underway when Adrian and Javier started collaborating.

From that time forward, the whole project remained organic and continued to develop and evolve right until the last stages. New versions of the animatics appeared regularly.

Javier said, “Defining the style, both in terms of a look and as a production technique, was tricky. In fact, early on Adrian was interested in setting up a style that would show the scenes being drawn onto the screen, as if Conor and his mother are still creating them. In the end, achieving that proved impractical, but we did achieve a progressive style that evolves from the beginning of the first tale to the end of the second one. We start with a basically 2D watercolour look and progress to a more truly 3D appearance and process, as the story and reality draw closer together in Conor’s imagination.”

This stylistic addition to the storytelling was quite successful for them. Important references the director Juan Antonio Bayona chose for the production were ‘The Tale of the Three Brothers’ animation from Harry Potter, and various classic, old-time 2D animated films.

Mixed Pipeline

Recognising that pleasing modern audiences would require adopting an essentially 3D approach to these animations, creating a 2D-inspired style was nevertheless very attractive to Javier and Adrian. Both of them had always admired classic 2D animation, and liked creating projects enhanced with dense, fine details drawn or painted over the characters and environments, and an artist’s finish, similar to living paintings.

The project pipeline for achieving this look and style was not simple to define. “When I’m leading a production team, I prefer to focus on the final images instead of imposing a particular software across a whole production team,” said Javier. “Glassworks’ artists were variously using Maya, Softimage and Cinema 4D depending on what they were used to, using several different renderers appropriate to those tools. Our team was generally only about 20 to 25 artists, except at the point when we were turning out a lot of 3D effects and needed a few more 3D specialists.”

The ability to mix different software within one pipeline is a trend Javier likes, due at least partly to developments like the Alembic interchange file format for CG assets, now used for visual effects and animation. The applications themselves are also more compatible, or can be bridged with scripting, for example.

Frame by Frame, Layer by Layer

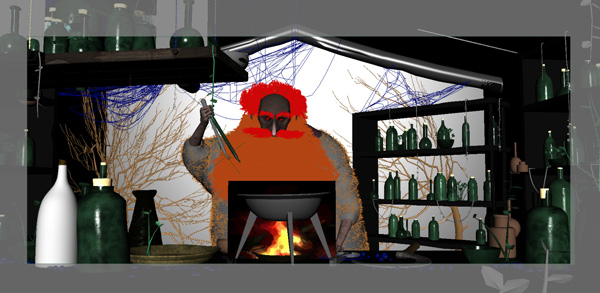

The animated characters for Conor’s stories were designed to give a simple, slightly stylized impression so that viewers might feel inclined to invent the story alongside Conor. But they are more involved than they look. For example, the rigging is fairly complex. The horse breaks into a full gallop and the horsemen engage in fighting manoeuvres. The faceless models represent heroes and villains instead of specific characters, but are built with character FX such as cloth and hair simulations.

Trying to balance their evolving, painted look with the need to portray Conor’s reality was approached with intensive layering for each character and across the backgrounds. The frames were created by outputting the layers as renders, painting or sketching the tiny, distinctive details on top, frame-by-frame, and then compositing all elements together at the end.

This practice affected the different teams at different points in production. “Compositing also had to evolve with the animation style. At the beginning of the first tale, the look and approach was closer to 2D painting. By the end, the compositing was mainly done in Nuke in order to handle the range of layers containing 3D effects, unusual lights, 3D models including the Monster, and even the inclusion of Conor as a live action element shot on green screen,” Javier said. “At those moments it was harder to integrate those elements and we needed the heavier compositor.”

Meeting the Monster

They obtained the 3D model and the rig for the Monster from El Ranchito visual effects company in Madrid, which included its complex textures. This model was created by MPC, the team that animated most of the Monster in the live action part of the movie.

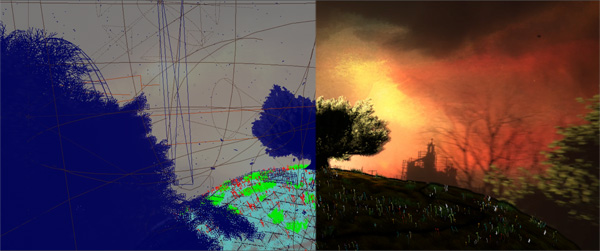

The introduction of the Monster into the action called for a more 3D approach across the frames, especially in the second story when we see genuine 3D effects and simulations – destruction, explosions, 3D lighting effects, stormy skies and more fire. The environments were bigger with more complicated combinations of element types.

Actual production of both stories lasted about 18 months. Through the period Glassworks were responsible for producing 2-week reviews in the form of breakdown clips that demonstrate the work to the production, including the director and producers. This created extra work, of course, but enforced an awareness of pacing and organization. For example the extensive layers were all shown, both for backgrounds and characters. You can see these in the compilation below.

Also, each story was to give the appearance of unfolding as a single shot. At times they did need to create multiple cameras to move the story along but the pieces of animation were carefully cut together to form invisible transitions in between. Glassworks delivered the animations as edited stories to the production editorial, who would then rework the cut slightly to fit their own edit, occasionally requesting extra shots from the team. www.glassworksbarcelona.com

Words: Adriene Hurst

Images: Courtesy of Glassworks Barcelona