Double Negative created all of the visual effects for ‘Inception’, roughly 500 shots in the final film. According to VFX Supervisor Paul Franklin, nearly all of them required tight collaboration between the special effects and visual effects teams.From Digital Media World Magazine

|

|

|

Paul had already worked with Director Chris Nolan on two of the Batman films, ‘Batman Begins’ and ‘The Dark Knight’. “Chris always demands absolute photorealism in effects. In this case, the characters as dreamers manipulate the world around them in order to carry out the ‘dream heist’ they are committed to setting up. Making unreal events feel as real as our dreams feel was very challenging.” Dreamtime To produce a protracted sequence in which a van holding all of the film’s main characters tumbles slowly from a bridge into a river in super slow motion, the special effects supervisor Chris Corbould and his team rigged real vans and fired them through the crash barrier off the Commodore Heim Bridge at Long Beach near LA, an old bridge built in the 1940s that Paul described as looking like “the Eiffel Tower turned on its side and painted green”. These falling vehicles were shot with a Photo-Sonic 4ER, a film camera that loads standard film but can shoot at frame rates up to 1200fps, and a Phantom digital camera, able to shoot up to 4000fps. “They typically shot at 360 to 700fps, which meant time could be slowed down to a crawl, giving the impression of a van suspended without gravity. This was important to show the variable rates of time from one part of the dream to another.” “In preproduction, we had experimented with how far we could slow down footage shot at different frame rates,” Paul said. “Tests shot with normal and high-speed cameras were taken into Shake. We found that shots of clearly defined shapes against clear backgrounds worked well. The software locked onto the shapes and let us slow the frame rate right down. But when the original shot contained motion blur, the results retained the blur, which usually had to be painted out.” Crossing Layers Paul said, “We had three shots like this. When we tried to retime the footage the layers simply fell apart, and we wound up having to mostly re-build them in CG by projecting the vehicle onto geometry and adding layers and layers of CG rain and splashes. So, we were often figuring out how to proceed as we went along, and had to break some rules.” Penrose Steps |

|

|

| In previs, Double Negative worked out exactly where to place the camera and the exact dimensions of the set. They gave these to the Art Department, who built the set to precisely match their measurements. They also liaised with the camera department and refined the camera placement and the type of crane to use to capture the set at the correct angle. Accuracy was critical. They decided on a 50ft Super Techno crane which, when fully extended, left only about an inch clearance under the ceiling of the building.

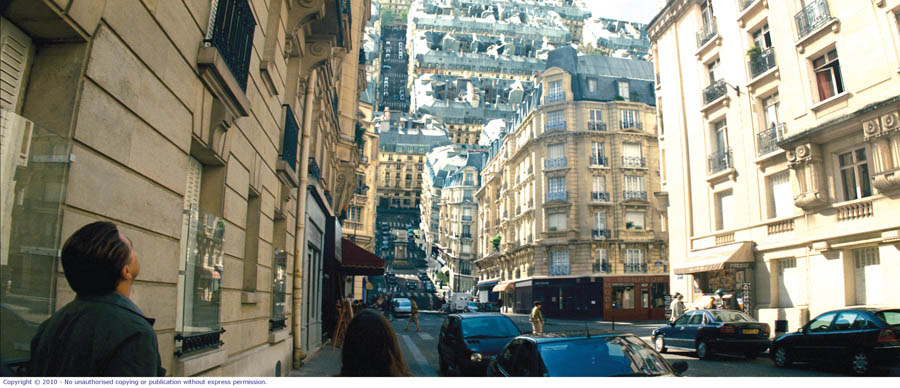

“Without having done a full laser survey and comprehensive previs, I really don’t think we could have achieved these shots. We knew just how it would look by simulating the lenses as well. Thus, previs became useful for such shots. We also used a similar approach for VFX shot layout – what now is called post-vis – that allowed Chris to approach shots differently after the shoot. He might say, ‘We need a shot that does THIS, but our footage looks like THAT. It hasn’t been shot for it all. What can we put together?’” Cubic Paris “Before shooting ‘Batman Begins’, we had spent time on the streets of Chicago, looking at drawbridges across the Chicago River. When these bridges fold up, they lift the entire road surface with the sidewalk, street lamps and furniture all plugged into the bridge deck. If you are standing at the opposite end of the street, the whole road appears to be folding over. ‘What if,’ we asked ourselves, ‘it continued folding right overhead, hinging a second time into a giant cube?’” Paul said. Nowhere To Hide They had to make sure that, once they had the sequence in post, they would have every detail they would need to build the folded streets to match Wally Pfister’s sharp, clear, high-contrast photography. “Everything happened in bright daylight as well, unlike Batman – we had nowhere to hide in terms of detail, no shadows even. We had to reach a level photo-realism we’d barely touched before.” Before the shoot, the Double Negative crew spent two or three weeks on location with Lidar VFX Services, a company from Seattle, to document to area, photographing and taking survey measurements and Lidar scans of about four blocks of the city. “We simply didn’t know at that stage exactly what Chris would want to do. We wanted enough documentation for a total reconstruction for unexpected bridging shots, for example, that may not have been recorded on film. Texture Mapping Face to Face “Chris Corbould’s team built a huge mirrored door 8ft by 16 ft that swung on a giant hinge to load into position and produce reflections of the actors to work with. But, of course, that was only one mirror. We could never have managed two – it was that big and heavy to get into place. Also, in the scheme of things, it wasn’t even as big as we really needed. A mirror of about 20ft by 40ft would have been required to cover the scene, but the one we had already weighed 800 lbs and took several men to push into place.” “It also reflected everything, not just Cobb and Ariadne but also the camera crew and equipment, visible in all of our plates. We ended up having to rotoscope the actors completely off the backgrounds and replace everything in the reflections around them with a CG riverside environment. Then we created all the reflections between the mirrors, as raytraced reflections of a detailed model of the bridge. “In fact, even Cobb and Ariadne are mostly CG doubles because we didn’t have clean reflections of them in the mirrors. Fortunately, they were mostly out of focus so the point where live action changes to CG doubles is invisible. With each reflection, as well, you lose about a half a stop of exposure, causing them to recede into darkness. We had to cheat it a little to still show a recognizable bridge when they shattered the mirror. |

|

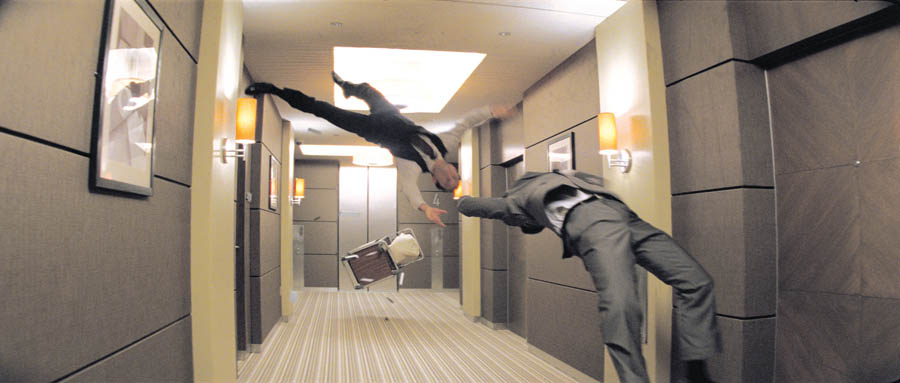

| Fragmented Physics Render times were especially heavy, on average about the heaviest they’ve done at Double Negative, due to the level of detail. Also, Chris wanted all effects completed at a minimum of 4K resolution, and some were done at 6 or 7K. They also made special IMAX versions of about 25 shots. The explosions in Paris were another special effects/visual effects collaboration. Chris Corbould worked out how to stage ‘fake’ explosions along the street with compressed nitrogen cannons firing debris up into the air, such as fruit made of foam, paper and other lightweight objects. These were shot with high-speed cameras that Paul’s team used to create a floating look, as if hanging in mid-air. “Ariadne, in her panic, had lost control of the physics in her dream,” explained Paul. “The laws of nature break down and everything fragments. It wasn’t to look as though a bomb had gone off, just a disintegration of physics letting everything fly apart.” The high-speed footage was effective but they couldn’t fill the entire street with practical objects nor sustain them for very long without CG. More important, they couldn’t have involved more substantial objects like bottles, cans and cobblestones from the street, in the same way. Gravity Revolution “The crew worked out how to attach the camera inside the set, moving back and forth on a dolly, which gives the fighting great dynamism and was inspired partly by Stanley Kubrick’s work on ‘2001’ for which rotating sets were also built,” said Paul. “The difference here was the dynamism created by the movement of the camera and its use in a high action scene. “However, when the scene changes to full zero-gravity, visual effects were needed to augment the practical effects. For this we built a vertical version of the corridor, that is, on its end, and lowered the actors down into it on wires with the camera down at the bottom pointing up at them.” The actors mostly hid their own wires, but the stunt rigs were very evident as they bounced around and needed some challenging rig removal due to the fast-paced action. Any visible wires needed very precise roto’ing to paint out and restore the background. Fighting Fit Paul thinks that capturing this scene as live action gives it an immediacy and a kind of ‘messiness’ that would have been missing from a CG recreation, though it may have been just as exciting. It might be compared to the elegant, highly stylized fighting in ‘The Matrix’. Living in Limbo The design of the city arose partly from Chris’ and Paul’s own interest in early 20th century modernist architecture. Though the buildings do not exist in reality, they are inspired by such architects as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropias. “Limbo City, in one respect, represents the history of modern architecture. Starting on the outskirts, you have early 1920s modernism and Bauhaus influenced designs, Russian constructivism and the International Style. But as you walk through it, you pass through all the different stages of architecture until you reach the centre with colossal towering buildings, still inspired by Le Corbusier but taken to an extreme degree, a thousand feet high, for example. “In the dream, so much time has passed since Cobb and Mal built the city that it’s now crumbling back into the sea and serves as an indicator of Cobb’s subconscious mind and mental state. Chris didn’t want the buildings to simply appear derelict. He wanted them to be monumental, with aspects of natural land forms like glaciers or cliffs.” Sculptural Approach Refining this software took a few months of iteration to produce the models, and resulted in a city with a complex geometric architectural layout that, seen from a distance, had an organic quality, looking like a series of eroding cliffs. To finish, they added collapsing buildings, not falling the way real buildings do when demolished but the way icebergs break off the face of a glacier, pulled by weight and affected by air resistance. The team spent lots of time looking at demolished buildings, collapsed, damaged, derelict housing projects to give it an eerie, apocalyptic feeling as well. |

|

| Limbo Square Deeper into Limbo City where the damage is less pronounced, confined mostly to broken windows, we encounter Cobb pointing out specific buildings on Limbo Square, encompassing diverse architectural styles and different houses he and Mal had lived in, based on various sources. Mal’s childhood home is based on a real house located near Paris, which was photographed and made into a digital model. Others were modelled from buildings Double Negative sourced themselves. But how could they be presented without looking like a mismatched collection of buildings in a theme park? They shot plates of a large reflecting pool at the Department of Water and Power in LA and used it to position the building as though they were floating in the water around this pool. They started with the real pool but had to replace most of the water digitally and made it much larger to accommodate all the buildings. The 3D artists spent a huge amount of time detailing, adding damage and dereliction and, above all, photorealistic lighting. Paul reflected on the project. “The most exciting part for me about working on this film was the chance to work with a director like Chris. He’s very demanding and remains in total control of his films as writer, director, producer – in short, an auteur. But he is also very collaborative, listens to everyone’s ideas and uses any idea that is genuinely good. In consequence, the team members have a creative investment in the film, and do their best work.” Massive Miniature The set in Calgary represented a portion of the fortress at full scale. Ian went on location to carry out a photographic survey, and take measurements and lighting reference. “It was solidly made of timber, finished to closely resemble concrete and with real icicles. Our miniature represented about 60 percent of the real building, the set showed about five per cent. Any full establishing shots of it were provided as matte paintings from Double Negative.” Shared Previs An important reason for this consistency across the production is time. As they developed and planned the shot – angles, approaches and so on – with Paul’s team in the animation phase of the collapse, his crew could meanwhile keep building. By the time Double Negative’s final previs was approved, New Deal could be preparing pieces of their model for assembly without concern about deviating from the plans. Working everything out digitally first before committing to materials also keeps them close to the Art Department. Another compromise came with the venue for the explosion. They would ideally have staged it with more space but the budget didn’t cover relocating the model. So they kept it in the back lot of their premises. Also, the scale and amount of the fortress and mountainside they built was dictated partly by space, and partly by how much they needed to produce the right look and interaction for the collapse. Everything else in the shot could be extended with digital matte paintings by Double Negative. Paul shot lots of mountain reference, as Ian did, so both teams’ rocks, for example, matched. The model breaks apart onto their model mountain, but surrounding it is green screen to give Double Negative some scope to extend the shot out. But everything involving the break up and fall down the mountain was achieved in miniature. They aimed to maximise the available model to create the best effect. The y shot everything with Vista Vision film cameras, which have a larger format than a regular 35mm camera and will hold up for enlargements filling the IMAX screen. However, the highest frame rate of these cameras is 72fps. Miniatures are typically shot at a higher rate to be able to slow the footage. This limitation was one more factor in choosing the 1/6 scale for the miniature. “New Deal takes a lot of care to make their shoot match first unit expectations,” Ian explained. “We need to ensure that the miniature performs as shown in the previs. Therefore, much of the destruction was not a result of the pyrotechnics and explosives but of mechanical effects built into the model. These were tested extensively as well. In this case Chris Nolan had a precise vision of the collapse. The tower at the front should collapse first, followed by the buildings at the back. It was also meant to be a controlled demolition in the story – characters are seen planting bombs along the bottom, causing a fall from the bottom up, and from the front to the back. Choreography |

|

| The building could thus be collapsed with out explosives. Even better, we could have another go should things not look quite right the first time – which is exactly what we did. Although we did have to make two sets of outer skins for the buildings, the steel internal structures could be re-used.” The collapse comprised about 200 small events – explosions, cable releases, dropping elevators – all choreographed and timed out with electronic timers to 0.001 second. While the real event, coordinated together took 5 1/2 seconds, on screen it lasted about three times that long. Retiming gave it the correct gravity but also, as the back buildings follow the front, an explosion and lighting was timed to go off behind the building as it fell. The previs was critical to working out, frame by frame, where explosions and events should be placed and how to time them. They needed the two takes but parts of each were useful, due to careful planning. Timing Boxes Lighting was a genuine concern. Paul advised them that most of the live action was being shot three-quarter back-lit. To plan the best position for their model, they also used a 3D model of their back lot where the shot would take place, complete with sunlight angles at different times. Based on best information, they positioned the miniature and scheduled the shoot. However, on the day, the live action shoot in Canada was shot right after a snow storm under suffused light. By great good fortune, the LA afternoon New Deal had planned their own shoot for also turned up overcast. “I was worried, but actually my cool-headed Producer David Sanger assured me it would work out. Otherwise,” Ian admitted, “I’m not sure how we would have proceeded.” Complexity |

|

| Words: Adriene Hurst Images courtesy of Warner Bros Pictures |

| Featured in Digital Media World. Subscribe to the print edition of the magazine and receive the full story with all the images delivered to you.Only$79 per year. PDF version only $29 per yearsubscribe |