‘John Carter of Mars’ is the largest creature project Double Negative has ever undertaken, requiring two and a half years of work. Updating the facility’s pipeline to meet the demand resulted in an exciting new Creature FX division.

| Double Negativestarted working on JCM during pre-production in May 2009. Principle photography began in January 2010 and after a six month shoot, their team began on post production, continuing from June 2010 all the way through to December 2011, under VFX Supervisor Peter Chiang.

The artists created nearly all the movie’s creatures plus a selection of environments, all of which needed to coordinate with the work of Cinesite, the facility responsible for the majority of the project’s CG sets, and the live action. The Utah desert, wide open, barren country under dazzling bright sunlight, was the shoot location chosen to represent the Martian landscape. |

|

|

|

| Touching Down on Mars The Double Negative team’s work began with extensive on set data capture including HDRI using a Spheron Spherocam HDR, and photographic stills for texture and photogrammetry. “We had witness cameras to aid tracking and used a Leica HDS6200 for laser scanning. We also shot helicopter plates and photographs for image based modelling to recreate the terrain and geology for certain locations,” said Peter. “Our team and Cinesite’s shared a lot of geometry and textures, and all the on set data was compiled into a database for easy access.” The team’s detailed on-set data capture would not only be required for accurate tracking and placement of their creatures into the live action. They were also asked to create some of the especially creature-heavy environments in the film - the White Ape arena, internal views of the Thark’s city and exteriors for the Temple of Iss. |

|

|

|

| Peter explained that Andrew always wanted to use as much of the real environment as possible. “The set extensions enhanced what was already present in the locations’ structure and geology. He wanted to evoke a past civilisation and that we were seeing the remnants of much grander scale. Concept artist Ryan Church and production designer Nathan Crowley had produced a library of beautiful images covering all the major sets. The location scouts were actually done after we joined the project, so we developed the looks further as we went along.

Finished Image In the pipeline, Maya was used as the foundation for all modelling, and for rigging and animating the creatures, with numerous proprietary plug-ins and pipeline tools built around it. All the costume and fur dynamics were handled through a combination of Maya and Houdini. |

|

|

|

| By the time Double Negative joined the film, Legacy had spent a year designing the creatures with director Andrew Stanton, and could provide Double Negative with ZBrush models to help start building their CG creatures. As well as the high level of believability the director expected, what made the creatures for this movie challenging is the amount of screen time they have, numbers of them within the frame, closeness to camera, and the range of actions in their performances. They also required complex interactions with practical and CG sets, and with CG and real characters.

Martian Tribe |

|

|

|

| Co-Animation Supervisor Steve Aplin described creating a back story for the Tharks as a tribe. “We began in pre-production by creating a number of vignettes about how Thark day to day life might look if a nature documentary camera crew were to come across the Tharks by accident and wanted to observe their behaviour,” he said. “We looked at documentary footage of African tribes, such as the Dassanech and Massai, as well as more brutal cultural reference depicted in Viking films. Andrew was always pushing the energy of these characters, and how quickly they could transition from stoic, Clint Eastwood type personalities to ruthless, deadly machines in a split second.

Although similar to people, the Tharks are very tall, have two sets of arms, no nose and external bones curving around their faces. Nevertheless, they were always regarded as characters that needed to deliver a specific performance. The animation team, led by Steve and his co-animation supervisor Eamonn Butler, worked hard with Andrew to convey this feeling. Early studies established a lot of the character traits and this led the requirements for the look development. Skin Deep |

|

|

|

| These creatures’ textures were incredibly detailed. The artists began with high resolution images, separating them out into different layers and adding bespoke painting to give unique detail to each individual Thark. Texturing was done with a combination of Bodypaint, Photoshop and Mari. The harsh desert light made it harder to balance the specular values of the skin and differentiate this from the moisture and sweat on the Tharks while keeping them dry and sun blasted.

Eye to Eye “The Thark actors were always shot with the correct eye line either on stilts, on boxes or decking or walking around with a backpack with a Thark head at the correct height for the character. We also had to prevent the very tall Tharks from overwhelming the hero John Carter and reducing his impact in scenes. Fortunately, Andrew’s eye for composition and staging helped with effective layouts for the shots.” |

|

|

|

| Once they had viewed a rough cut of the film they were able to determine the level of detail we needed for the Tharks close up. The lighting started with the HDRI but they soon found additional tweaks were needed to emphasise the geometry and highlight narrative aspects in the shot. Lighting and rendering relied on a proprietary system built around both Maya and Pixar's RenderMan.

Performance Ready “Andrew was very clear from the get-go that the Tharks had to stand next to the live action actors and be inseparable in their level of realism - they had to be able to hold their own. He also wanted a very tangible connection between the digital and live action worlds, which is why he was keen to have the Thark actors on set, acting with the live action actors with their eyes at the same height as their digital replacements.” |

|

|

|

| Layered Crowd When the Tharks appear in the film’s huge crowd scenes, a three-layer approach was required, based on an animation library consisting of more than 800 unique pieces of animation supervised by animator Stephen Enticott. The first layer consisted of two or three hero rows of Tharks closest to camera. Their performance was hand animated, giving Andrew the flexibility to direct the foreground action. The next layer was for mid ground action, which the animators hand-placed using the library cycles, while composing the shot to draw the viewer’s eye around the frame as the director needed. The final, third layer covers all distant Tharks and involved the greatest numbers, under the banner of Crowd Simulation supervised by Eugénie von Tunzelmann, FX Supervisor and crowd specialist. “She and her team used the animation library to populate vast areas of the background via a proprietary particle instancing tool through Houdini,” Steve explained. “They could digitally airbrush an area with particles, replaced with animation at render time, and blended different pre-animated sections of motion together to maintain richness and complexity in the backgrounds.” |

|

|

|

| “We shot several motion capture sessions with performers we had auditioned for various Thark attributes. Some had specific attitudes we keyed into, some were physically similar in build, and some were more athletic. A good combination of the three was actually discovered in one of our lead animators Thomas Ward. When applied to a Thark, his motions were solid fit and great starting points for many of our cycles.

Facial Performance |

|

|

|

| Steve noted that the centre of the Tharks' faces were an issue from the start. “The nose on a human face is such a visual anchor. Without one, we asked the question - what do we feel the underlying anatomical structure would be, and how can we accentuate it to achieve the feel of a nose being there? We came up with a series of muscles and tendons which we could fire quickly before key mouth shapes were dialled in, as well as tying the eyes and mouth together via the nasal labial folds to avoid a dead area in the space between.

“In addition, the nostrils on the Tharks were actually on top of their heads, so we ensured that they performed in conjunction with the rest of the face to reflect what regular nostrils would do. It's a small detail that most people won't even notice, but it would take away from the performance if they weren't there. Finally, we layered facial skin simulations on top of everything to tie all the relative areas of the face together, and give the skin additional secondary jiggle that really paid off in those extreme close ups.” |

|

|

|

| The Tharks each have two pairs of arms as well, posing a different kind of challenge. While Andrew didn't want the arms to act independently as if the Tharks had two brains working toward different ideas, 'twinning' the actions gave an automated feel to the performance. “We chose the upper set of arms as the primary action tools, and worked in the secondary lower set to support them. At times his meant introducing a partial twinning, offset enough to not be distracting.

New Creature FX Team Creature FX at Double Negative is a relatively new discipline within the realm of creature work. It was developed during John Carter to bridge the gap between the mesh centric world of rigging, and lighting and rendering. Creature FX supervisor Richard Clark explained that traditionally, creature TDs and riggers focus on making the mesh represent as much of the anatomical detail as possible and can animate, deform and drive the mesh in many ways. “While this approach has benefits, the artists can never use a mesh matching the level of detail seen in a ZBrush sculpt,” he said. |

|

|

|

|

|

| “Sculptors and lighting artists have the opposite problem, as their disciplines are not animation centric. They can achieve almost limitless levels of detail, but virtually have no way to breath life into that detail. To get the best of both worlds we have developed a new discipline that plays on the strengths of each one. Creature FX artists are essentially creature TDs, but work with lighting and renders to turn those amazing details into something that moves and compliments the character animation work.”

Flexing Muscles dnBeouf also drove mesh deformations such as muscle flexing on the rig, tendon deformation, dynamic wrinkles, skin sliding and compression data for skin colour changes. Richard said, “This gave us near real-time feedback for key framing to the performance. The result was viewed in the render to asses it with impact of lighting. Once approved a mesh cache was delivered to the lighting team to render for the final.” |

|

|

|

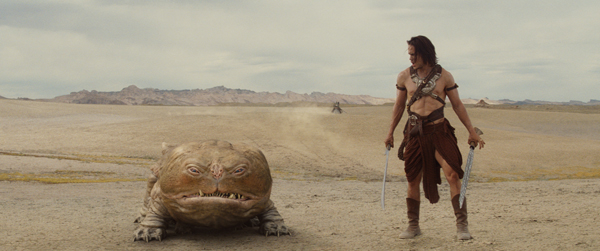

| Man’s Best Friend Woola, John Carter’s loyal companion and protector, was possibly the most fun creature, similar to a dog combining a fairly grotesque design with endearing performances. Mysteriously, although his build is fat and stubby, he is able to move at heroic speeds over most terrains. Steve agreed that he doesn’t have the most instantly appealing face. “We started out by making his movement pretty cartoony and extreme, but in one of the first sequences we animated we found that by having Woola do less and appear more vacant and attentive to Carter’s every move, he became far more lovable. The lead animator for Woola, Craig Bardsley, focused his team on reference of bull dogs, pugs and boxers for locomotion and character traits. They spent a lot of time exploring how a creature of 400lbs could move at speeds up to 200mph, yet stop on a dime. By displacing his weight in number of creative ways they managed to avoid letting him feel like a Tex Avery cartoon. |

|

|

|

| “For the head animation, Andrew always reminded us that you should be able to gain a performance for him by keying off something as simple as a sock puppet. If you could make a sock puppet emote, Woola would be similarly effective. Such behaviour as the way a dog tilts its head while trying to understand its owner’s words really embellished Woola’s character. His tongue was also fun to animate, based on a dog’s tongue. Effects artists were able to add a separate layer of jiggle motion over the top of the key frame animation to really amp up the fleshy feel of the tongue motion, especially on the thinner edges surrounding it.”

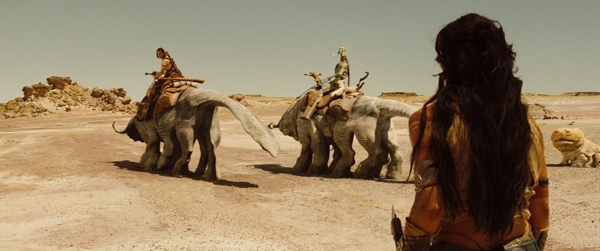

Desert Transport |

|

|

|

| On set, the actors rode on motorized Thoat rigs that created saddle motion derived from the animation cycles. Steve said, “Once the Thoat team had animated various walks, canters and gallops and recorded the degrees of rotation and levels of translation of the CG saddle on them, special effects supervisor Chris Corbold and his team used these to build and drive the movement of the live action saddles on set, giving the actors the correct motion for the animators to use later on the CG Thoats superimposed underneath.

Because no motion capture was recorded on set, the Tharks were actually more forgiving because we could adjust their motion more easily to fit them to the Thoats. Ape Interaction |

|

|

|

|

Andrew's concept department had already heavily designed the Apes before production began, which needed only slight alteration during the animation test phase to accommodate a more expressive range of motion. Their lead animator Ben Forster had his team looking at silverback gorillas in particular for natural motion to key from. As they were at least ten times bigger than the average real ape, additional weight passes were added and their ferocity was cranked up to the next level. Steve said, “We struck a careful balance between the speed the Apes had to move about the arena and maintaining the sense of extreme weight. They are also blind and seek Carter out by their sense of smell, so this had to be worked into their performance as well, in a way that the viewer would immediately understand.” |