Josh Van Zuylen is a digital artist and designer specializing in environmental work. He currently works at Zero Latency, a developer of multiplayer virtual reality experiences in Melbourne, Australia, and his experience ranges from IOS to AAA console games and VR worlds. Since studying for his diploma in Game Art at the Academy of Interactive Entertainment, Josh remains fascinated by dystopian science fiction culture, inspired by the work of Mike Pondsmith, Syd Mead and David Snyder.

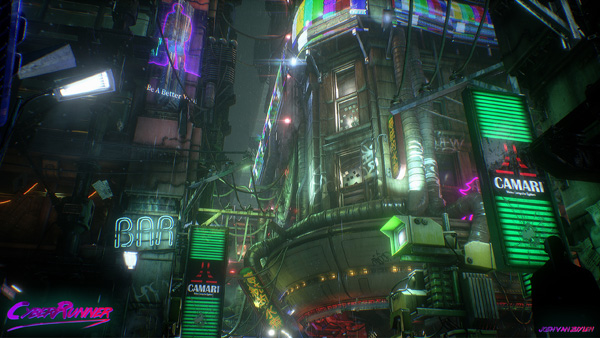

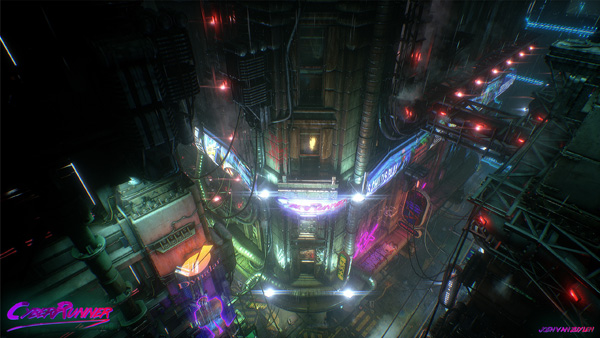

Josh’s own project of this genre titled ‘CyberRunner’ is, of course, influenced by Cyberpunk and BladeRunner styles - heavily detailed and textured, beautifully lit, spanning city streets cluttered with odd vehicles and towering buildings. But it also has an original look, best appreciated through his deliberately animated camera that explores the environment from top to bottom while maintaining a feeling of mystery as it moves around each corner.

Vizualisation

Following his initial inspiration, Josh started the project by creating several white box visualizations in 3D to set up the main layouts with large geometric primitives and basic lighting in Photoshop on a Wacom Intuos Pro tablet. When he was happy with the design at that level, he moved into proxy modelling to flesh out the scope and visual theme for the world. He modelled the shapes just enough to form silhouettes so that the assets began to look more like the end result without spending a lot of time on development, thus enabling faster revisions.

He has found this is a good approach when trying to get original designs underway without concept art to lean on. Then once he had created these proxy models and had a clear idea of where the project was headed, he could already move into production. “Pre-production is a critical stage but is definitely not the easiest. If you can get any edge over looming deadlines you should take it,” he said.

“Using a Wacom tablet means you can work faster from the start of the project, and maintain a more free flowing working style. In the conceptual stages you can model faster than you could do traditionally with a mouse, shoot back ideas in 3D to the client faster and, as in the case of Cyber Runner, be your own pre-production and production team.” Concept modelling, UV mapping, baking, texturing, engine implementation and shader creation - all stages were done on the tablet.

Model Design at 4K

CyberRunner was modelled primarily in Autodesk Maya. Designing models at 4K resolution - and their real-time game engine counterparts - was made possible and accelerated by using the Unreal Engine 4, Quixel Megascan library, described below, and Substance procedural and PBR texturing software developed for game engines.

Josh said, “Maya is very compatible with working with graphic tablets and no UI. I have a work philosophy of removing any unnecessary distractions and not pressing any menu buttons. Because Maya has on-screen quick action menus, gestures and a hotkey editor that work on a tablet, you spend less time moving the cursor across the screen. This sounds like a small detail but if you were to record how much time is spent travelling to a button over the course of a session, you would be amazed.

“You don’t need to continually track the mouse pointer on the tablet because it is wherever your hand is. This means you can drag and drop an object in one motion onto a location as small as a node point in Unreal’s Material editor. UV editing is the same as modelling in most respects – Maya’s onscreen commands allow you to execute 12 actions in about two seconds using a graphics tablet, which would be noticeably clunkier using a mouse. You also don’t need to switch to a different input device just to bake or export something,”

Environmental Management

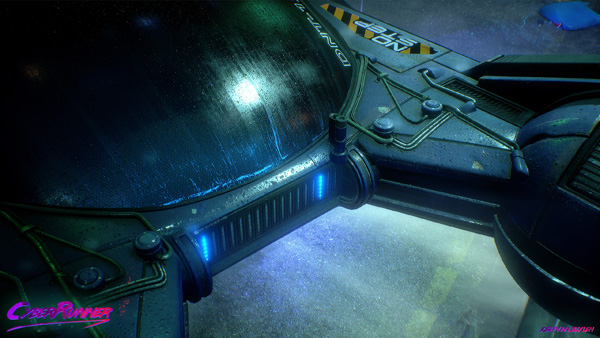

Josh’s high-resolution models usually consist of a huge number of polygons to support the level of detail he wants to show. This may be modelled in Maya, using subdivision surfaces [Sub-D] to control the overall polygon count, or if it’s a slightly more organic surface, he might sculpt it in Zbrush.

“An example of this would be the overly-engineered dumpster [above]in CyberRunner, for which the high-resolution Sub-D model was around 25 million polygons,” he said. “I would then transfer that high-resolution data to a low-resolution mesh that was only 5,000 polygons at its highest level of detail and runs in-game quite fast, while retaining all high-resolution details.”

The comprehensive project demanded a total of six months solid work in production. Josh described it as huge in scale, especially as a solo personal assignment. It was an iterative process that included set dressing, developing several lighting scenarios, shader and weather systems, animation and cinematography.

“At a certain stage, I needed to rebuild the entire environment because the scene hierarchy wasn’t working effectively. Most of those challenges related to lighting and object placement, lighting not contrasting correctly with where I wanted viewers to look or objects being orientated incorrectly. At one point the main focal point of the entire environment was wrong, and I literally ripped the environment in half and doubled the environment size to make the shot work.

Lights and Textures

Josh got to work on the lighting from the moment he had completed the look development stage, setting it up entirely inside of Unreal Engine 4 using a mix of real-time and baked lighting. “As soon as I came out of concepting the look and feel, I threw the concepts into Unreal Engine 4. Over the course of the project I rebuilt the lighting several times to fully realize the world I was trying to build. Baked lighting was mainly reserved for indirect lighting sources, and real-time lights were used where strong direction was needed.”

Josh took a lot of care on the surface textures of his assets. Some the surfaces are directly pulled from Quixel’s Megascans, which is a huge online library of high-res PBR (physically-based rendering) calibrated surface, vegetation and 3D scans, plus software for exporting and handling the downloaded scan data. Most only reference the physically accurate values from Quixel. The entire environment uses PBR, and makes use of shader settings to create the weather effects such as rain and dirt.

He said, “I took a lot of reference from Blade Runner and Cyberpunk universes to decide how I might portray surfaces in CyberRunner, aiming for a look overall that would make everything feel neglected and not very well looked after. Of course, I could have just covered everything with dirt, but I wanted to create a large variety of reflections across surfaces. Incorporating different types of metals and smooth surfaces, like paint, really helped break that up.”

Camera Story

The ultimate goal of the camera work in this project was to show off the world of CyberRunner, but Josh wanted to avoid a standard environment fly-through. He started blocking out videos in a trailer-like format to keep the viewer more interested, and viewing for a longer period.

“This was essential, as the environment is huge and it’s almost impossible to do all the work justice in a pass of less than a minute. The camera shots themselves were not inspired by anything in particular but are probably influenced most by my interest in storytelling in film and games,” he said.

“In my mind at the outset, I’d had a few key camera shots I decided I needed to make and had designed the world Based on those visions. From there, organically and iteratively, other more expressive camera shots became apparent to me and were incorporated. Of course, I had to set limits on what I could do - otherwise I could be making CyberRunner for the rest of my life.” www.wacom.com