With a shoot spanning three continents, ‘Killer Elite’ was an 18-month production and post-production project for Iloura's VFX team. VFX supervisor Julian Dimsey supervised on set at all locations.

|

|

| Starting with nine weeks of filming in Melbourne, Iloura’s home city, the crew went on to complete four weeks of pre-production and shooting in Wales, plus another week in Jordan, while VFX supervisor Julian Dimsey and visual effects coordinator Pippa Sheen picked up some stills and reference shots for matte paintings in London and Paris along the way. A large portion of the facility’s work on the project was devoted to transforming sets into far flung locations to fit the story, based on Ranulph Fiennes’ book ‘The Feather Men’ about a secret society of former hit men, set in 1980.

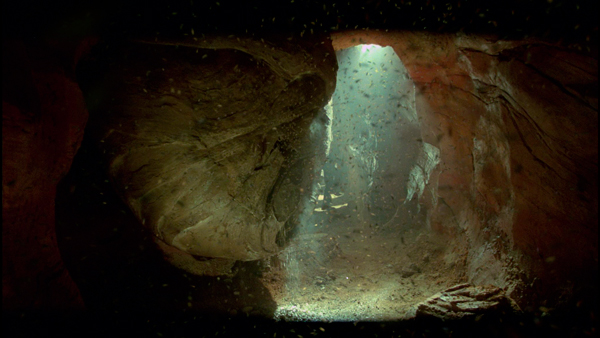

Action-Packed Julian attributes the amount of effects work the movie needed to three main factors – the multiple international settings, the dangerous high-action drama of many sequences and the 1980 time frame. Ilourawas involved at the pre-production stage starting in mid-2010 to plan and work through pre-vis with the director Gary McKendry, which was essential to manage the numerous high action sequences. Julian said, “Main unit would shoot the drama first with the lead actors, and second unit would follow, perhaps days or weeks later, to shoot the action portions. The crew might only have the pre-vis to show them exactly what the director was expecting to see. As well as the VFX team, pre-vis was a resource for the stunt team, Art Department and special effects crew.” Many shots involved shooting exteriors with wide, sweeping camera moves for which it would have been impossible to set up green screens. Consequently a number of set extensions needed the live action to be rotoscoped back onto the matte paintings, though fortunately some of the more complex action could be captured on green screen. One shot in which the lead actor slides down a sleight roof, for example, was shot on a set piece and could be composited into a live action plate. However, an extensive shoot at the docks in Williamstown in Melbourne was 100 per cent in camera, from which all live action had to be rotoscoped. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Authentic Imagery “In reality, using green screens for exterior shots in many films frequently doesn’t work out due to weather or just the nature of the location itself, and there are advantages to going without them,” Julian remarked. “They can restrict camera moves and demand multiple passes. What is better for the camera crew is usually better for the drama, if trickier for the effects artists! With or without green screen, lighting for element shoots is also much better captured on the same day in the same spot as the plate photography.” The movie’s principle photography was captured on 35mm film, while Julian shot the visual effects components mainly as digital stills to use for matte paintings, cutting and pasting imagery together for the wide vistas across the backgrounds, and to source textures for the occasional 3D elements. When moving elements were needed, or when camera moves caused enough perspective shift to need 3D work, he would shoot some footage on a Canon 5D. |

|

| While in Wales, where the camera crew shot some specific locations, Julian and Pippa went over to London for a day shooting vistas from rooftops capturing authentic elements to use in matte paintings for the film’s major rooftop chase sequence. When in the Middle East for the remaining sequences, Julian shot background plates and more stills of a wide variety of venues to enhance their desert shots. On the way back he and Pippa made a stop in Paris for more. “In short, any opportunity we found for genuine background plates and imagery for our work, we took. Stock imagery, moving or stills never quite satisfies requirements – the resolution, lighting, camera angles and so on never seem to be quite right,” he said.

Trains, Planes, Automobiles Contemporary aircraft and car designs were first sourced to give the director different options to choose from to fit the sequences. Blueprints for most of these are available online and examples of them can often be found in museums for texture photography. The art department would supply artwork for the paintwork. |

|

|

|

|

|

| If necessary they might even do some kit-bashing, using parts from similar vehicles of the same era to fill in areas they couldn’t find exact information for. The Paris Metro train was somewhat trickier, as there certainly weren’t any convenient examples for the team to photograph in Australia. The Internet was again a useful resource.

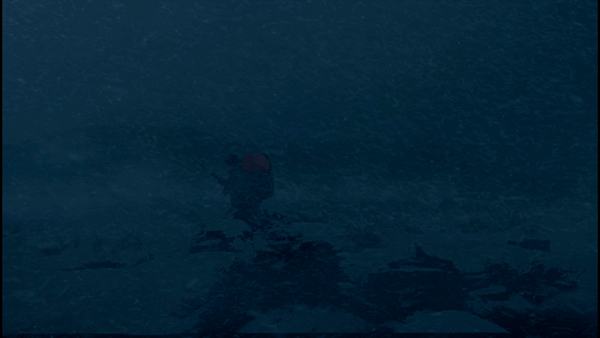

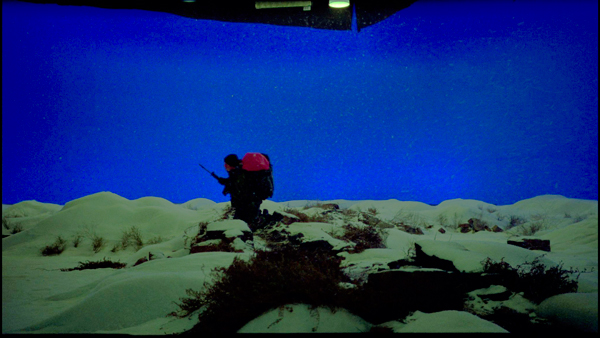

“A lot of flexibility and resourcefulness was needed on this project to make all the different types of scenes work,” Julian reflected. “In production, the pre-production work with Gary was a great starting point to get everyone working toward the same result, but if the shoot turned out windy or rainy and our plans weren’t working, we had to think on our feet of a Plan B that would still achieve what the director wanted, whatever the shooting conditions. “Back at the studio, the teams applied workflows and a pipeline that have been developed at Iloura over years of experience – we weren’t pushed so much in that respect. The challenge came from the complexity. Rooftop Chase Another challenging sequence was a night-time snow scene at Brecon Beacons when lead character Danny Bryce must assassinate an SAS agent in a snow storm, another mix of shooting on location in Wales plus a blue screen studio shoot in Australia. The exterior and interior shots needed continuity work, and the location shots, which had to be captured in daylight, needed day-for-night treatment. The falling snow had to interact consistently with the actors and the ground. All snow was artificial but on location it had only been placed on the ground while in the studio it also blew out from snow machines. This gave them some initial actor interaction to enhance in post, where they also extended the snowy backgrounds. |

|

|

|

| Smash Up The various car smashes included in the chase scenes each had to be handled differently. When a car smash was shot to look as though the camera was inside the villain’s vehicle, the impact itself was staged with stunt actors. But the critical shots with the actors were made up of a series of separately captured components, composited and cut together – the two actors inside their car, the criminals in another car, the road and some smashing glass. “It was tasks like this that added to our effects shot count. The car smash of the Mini on the freeway had to be worked out with different techniques. We really did shoot a Mini smashing into a truck but then had to go in to do extensive rig removals, add digital exploding glass, blood sprays and build parts of the vehicles in 3D to distort them further and enhance the violence,” Julian said. The stunt performances always required wire removals and occasional face replacements tracked onto stunt actors for the lead characters, depending on the angle of the shot. “The fast cutting style during the action sequences was, of course, very helpful to keep the shots short. But when we did have to replace faces the general approach is to get all the actors together for an extensive photo shoot under different lighting conditions at all angles, which allows the 2D and 3D teams to create digital versions. “We often do this in any case, before any specific need for it arises. It’s valuable to capture as much material as you can while the actors are available to you. Getting pickups later is often impossible, and expensive. It gives us more freedom in post because once we have those images we can rely on our own skills to adjust scale, lighting or perspective and make the shots look exactly as required.” On Track |

|

|

|

|

|

| “The main tracking requirements for us were on camera moves, which are pretty straightforward. Tracking an object onto something in a shot, combined with an independent camera move on top of that, is harder,” said Julian. “This is what we were doing for the film ‘Ghost Rider 2’, for example – tracking a burning skull onto the actor’s head, changing its scale as well as managing the camera moving independently from the actor.”

The producers as well as the director were receptive to different approaches to the visual effects, including different ways to shoot the scenes. Director of photography Simon Duggan knew how to get the most from the previs as well, and the editor John Gilbert was also open to suggestions. Compositing Workflow The team used Nuke for compositing and rotoscoping was done with either Nuke or Mocha. “Nuke allows you to write a rotoscoping script that the compositors can import and modify as required as part of their compositing script. In our workflow, the matte painter does his own small composite in Nuke to check his progress. That script will be passed to the lighting artists who enhance it with their elements, plus any 3D elements. All of this is handed to the compositing team, who then take the scripted components and polish the look,” Julian said. “Right from the beginning, while we are getting approvals on rough composites, everything has actually already been composited in Nuke, which allows us to return all the way back to alter an early stage if necessary, without affecting the workflow. Nothing has to be re-built to suit the different teams.” |

|

|

|

|

|

| Modelling was done in either Maya or 3ds Max, sculpting in Mudbox or ZBrush, and V-Ray is their main renderer. Photoshop is used for matte paintings and painted textures. Because they are rendering out of V-Ray, 3ds Max is convenient to use for light and therefore for dealing early on with the CG. “Re-lighting later in the composite is not as effective for this kind of work, where we find Nuke’s strength is its integration, layering everything, applying levels of defocus and grading elements down into the plate,” Julian said.

Road to Morocco "The opening sequence was changed to feature an assassination in Mexico and a three-way stand-off in the desert was added at the end,” said Julian. “Again, the weather transpired against them. Strangely it poured with rained in Morocco the day before their shoot, which meant the car chase through the desert had no dust swirling up behind, which made it feel lacking in speed and danger. Ten shots or so all needed dust composited in both to add excitement and to provide a screen allowing the hero characters to follow unnoticed behind the driver they are chasing.” Morocco introduced a further, unexpected continuity challenge in that while the houses all had the required pre-1980 looks, the neighbourhoods were filled with satellite dishes, sometimes as many as 40 or 50 per shot, modern signage, air conditioning units and other artefacts of modern life, which all had to be painted out. Colour and Cameras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

They carried out wedge tests – scanning test shots to digital, grading them in the Autodesk Lustre system, and getting a film out from the ARRI film recorder. Then they could process and print it to view in the same grading theatre, and compare the digital grade with the print. They also set up a first light system. Simon would shoot a series of stills on shoot days, decide with Gary McKendry the looks they wanted for specific scenes, and email these to Brett to use as reference for the rushes. Combined with phone conversations, this made it made clear how to proceed and was a good workflow. Simon was skilled at capturing as much of the look and mood on set as possible, so that Brett found the work was more about enhancing than creating looks. Looks That Kill Gary had specific looks in mind for each location in the story. While overall, the film kept a cool mood, the European and London looks for example, he called ‘bruised’ - deep plums and blues running toward yellow. In contrast, in Australia and Paris where the romantic angle of the story plays out, the scenes have more flattering, warmer lighting and were easier to differentiate from the rest of the film. While the early 1980s era of the story influenced the content of the film, Gary didn’t want the images to look as though they had been shot in those times. He wanted modern production values and a modern looking grade. The Middle East sequences were the most challenging in some respects. The sequences were not shot entirely either on or off location. Because only the wide shots in Jordan and the final scenes in Morocco were actually captured in desert environments, and the rest were shot in Melbourne, marrying up the two sets of footage was a challenge for the colourists. Also, the Morocco footage required a flexible approach in itself. When the weather turned stormy, as Julian described, they did what they could to bring a warmer, more desert-like quality to the images, although in the end the moody look suited the story better than the director expected. Autodesk Lustre is the facility’s system for feature films, which Brett likes for its ability to craft images for movies. “You have access to a lot of useful tools for feature-type grading, for example, allowing you to draw free form shapes to track to the images. You can key specific colours, and create a matte for a colour, skin tone, shadow or highlight.” Test Screenings Although the director and DP were not sitting in at grading sessions, they would both be available in the building while working on the edit to check progress and leave notes. When Simon had to go on to another project in the US during the grade, Brett would render out stills to email to him to check and give feedback. In terms of visual effects, it was essential first of all for the VFX team to have their effects reviews with Gary in the same setting that Brett’s team was grading in, so that when they saw their shots on the big screen, they could identify problems at that same size and resolution, with the same display medium. Second, when effects shots were approved and sent for inclusion in the reels to be graded, Julian would make sure the artists supplied a matte for the composited elements, for example, a sky they had replaced. This allowed the colourists, if necessary, to handle that composited element in isolation. For example, a sky replacement could receive a special treatment the director wanted. Quick Shots “When compositing portions of the digital stills into the 35mm frame the compositors could apply a grain effect, depth of field and so on to match the film’s look, of course, but for us, having those isolation mattes really made the shots work. We could drop them into the timeline with the rest of the footage, activate embedded mattes for the composited elements and just work on those areas.” The fast pace of the film also affected the grading. Brett explained that what matters to a colourist is not the overall length of a project but the number of shots it comprises. Each shot has to be addressed in context and in isolation. He said, “This film had a huge number of individual shots. It wasn’t a problem, just needed good management every time the camera changes. We would grade a handful of shots, run them back in real-time, grade again to refine them and iron out the small ‘wrinkles’ in the grade. www.iloura.com.au www.digitalpictures.com.au Words: Adriene Hurst |

|