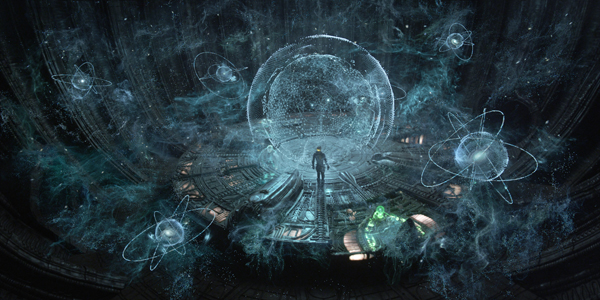

Fuel VFX put their expert design skills to work on the Orrery, the star spangled 3D hologram the Engineers of ‘Prometheus’ used as their map through the universe.

| The team atFuel VFXwas responsible for designing and creating a series of alien and futuristic human technology to help tell the story of ‘Prometheus’. They developed the holographic and light effects required to make the Orrery, the astronauts’ Holotable and several animated holographic characters look realistic and believable. | |

|

|

|

VFX Supervisor Paul Butterworth, leading the VFX team at Fuel, described the process of finding references and inspiration for the Orrery, a holographic three-dimensional mapping system the story’s astronauts discover on the alien planet. An orrery as a device is not new and, in fact, an image that the director Ridley Scott chose as a key reference was an 18th century painting called ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’. However, the ideas and concepts for the Engineer’s Orrery in ‘Prometheus’ had to be flung far into the future. Guiding Light For a starting point to the three-dimensional design and build, another set of references was sourced and shown to Ridley for his reactions and preferences – sculpture, classical paintings, even sounds and movie clips. The painting mentioned was among them, for example, showing mechanical hoops circling the sun to representing orbits reaching out into the universe. “Ridley’s concept called for a core at the centre, casting out light, as the place and time the Big Bang had occurred and scattered millions of tiny objects out in all directions,” Paul said. |

|

|

|

|

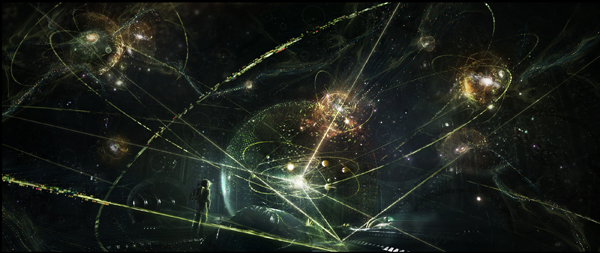

“That central location also acts like a magnifying bubble. The user might grab something from the surrounding space, holding every star and celestial body ever made, and as he moves it to the centre, it would be magnified, like moving your mouse over the Apple dock on a Mac computer. The user could then study this object under a volumetric lens. Orrery Story From these essential story ideas they developed the looks based on real nebulae and astronomical objects. Lead effects TD Roy Malhi developed a set-up and wrote several specific tools for simulating gassy clouds and embedding stars within those clouds that illuminated them. Fuel’s Art Department typically works alongside the effects artists, who can run tests as they work to show the art team, who then produce further artwork. Genetic Code |

|

|

|

|

“We based the idea on the Engineers’ interest in producing new species on various planets,” Paul said. “These elements - hoops and their ‘DNA’, nebulae, gas with the basic light set ups from the centre out - were the guiding features that compositing sequence supervisor Denis Scolar used to bring the complete machine together. It was built as an immersive, stereoscopic, experiential object and therefore, I designed it much more densely than I would for a mono project. Knowing the audience could use that extra dimension to see and understand the Orrery was exciting. “I really enjoyed it as a creative artist. My background is in design and illustration as well as live action photography and direction. Art direction was a major factor in developing the Orrery. We watched the shots in stereo many times over to plan every movement, not just up, down and across but objects passing in front of others, interacting or moving into the background.” Deep Image Tools “In a deep image system, your working environment is more like a cloud. You have access to all pixels, right back into the depth of the image as well as across it. You can then combine the render ‘clouds’ rather than confining the elements to a flat plane. Creatively, you can sign off the different elements at an early stage. As the overall project progresses, instead of locking off the final product and rendering whole shots, you can render one portion of your work at a time - in our case, the Engineers, the star formations, hoops and so on.” |

|

|

|

|

The principle advantage to this system was the ability to lock off rendered sections of this massive Orrery object - containing nearly one million polygons - as they went. A further advantage the team found was using elements rendered in one package to light those rendered in another. Compositing Challenges “The deep image system means you can render the gas cloud as required, then continue changing the ship animation and re-rendering only those elements, independent of the rest. As well as the designer, this set-up benefits the compositor, who has the freedom to manipulate details like camera effects, also independently of the rest of the render.” |

|

|

|

|

Fuel VFX submitted all shots to the production in stereo. The earliest concepts were mono but the team would begin planning for the 3D composition as soon as possible, because shots usually needed to be designed more densely than normal, like the Orrery. Paul said that balancing stereo compositions can be a challenge, and the team sometimes changed their compositing style in order to keep enough visual interest in the shots. Rotomation vs Mocap “It proved to be a very elegant way to work. It’s still hard work, requiring accuracy and retention form the animator, a but a great way to get performance sign-off especially when the director is not confident about including an animated character in a live action film,” said Paul. |

|

|

|

|

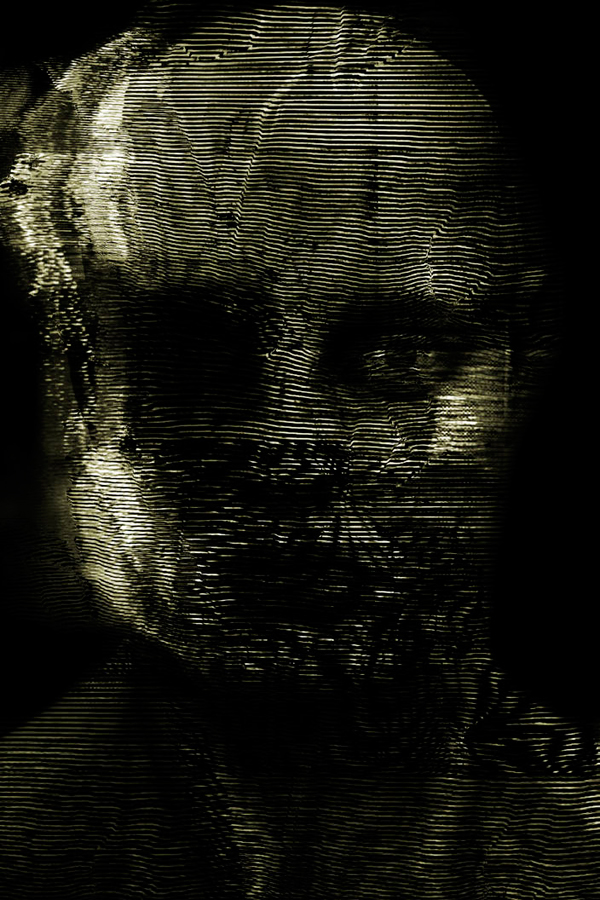

The first appearance of the holographic Engineers takes place within the pyramid as the characters run along a dark corridor. The very low light and unevenness of the floor interfered with the actors’ performance. “In this case we decided to use a 3D scan of each actor in his gear and built a detailed rig for him. The rig was then passed to a motion capture company in London, where they captured the actor’s performance in a more controlled, directable environment. This capture data was sent back to Fuel to apply to their rig and virtual character.” Ghosts of Engineers “But in this sophisticated, alien version, the walls of the building were projecting a 3 dimensional version of the characters that a viewer could see from multiple angles - and even fast forward, stop or reverse. Ridley also liked the notion of making the characters perform in ways that would suggest interesting possibilities to the audience,” he said. |

|

|

|

|

“For the look of the images, we deteriorated the model to give it a look resembling a broken TV image, showing various kinds of image degradation from missing sections and random bands of deterioration, to ‘dead pixels’ on a monitor. We tried to mix the familiar and scientific with the alien and fantastic.” Interactive light was an essential part of all of Fuel’s holographics. While this is a typical part of visual effects work, in stereo , the accuracy and completeness of the CG surfaces they generated for their lights all had to be perfect. Paul said, “We underestimated the effort required to line up shot for shot, pixel for pixel, the geometry in the caves, the Orrery, or on the control desk. In the case of the desk for example with its green energy effects, we weren’t building just one desk but a unique desk for every shot.” Fortunately they did have accurate LIDAR scans, survey data and drawings of all sets but it still became a huge task to re-model these surfaces perfectly for the Maya or Houdini lighting environment. When Paul had been on set for the key sequences, he had also simply walked through and around the set to get a feeling for relative positions of objects and where interactive lights would be important for realism. Cartographic Kit |

|

|

|

|

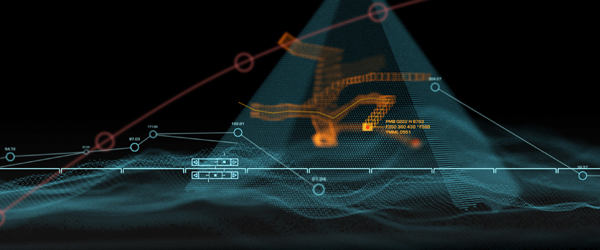

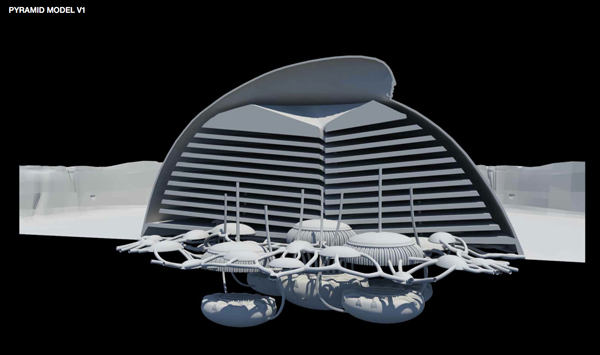

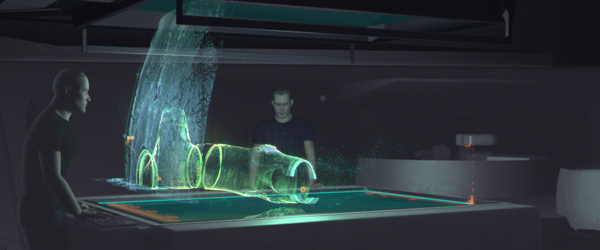

“The sets of the ship interior were beautiful to work with. Our initial brief and concept frame was pretty interesting – we knew the table would have a glass surface and could volumetrically project a map using survey data. We also knew there were probes that flew around inside the aliens’ buildings and as the devices scanned, they send data back to the table, interactively building a 3D map. But we had no idea yet what those buildings, the maps, the devices or the table looked like.” This prompted another quantity of concept frames to develop looks – should the map resemble an ant farm design? Would the alien pyramid itself have four walls or was it more of a dome? If it was a mountain-like structure, how far was it buried into the ground? “In short, the design had to answer a lot of structural questions. Inspired by the looks of laser and LIDAR scanning techniques, we decided that the mapping system would represent data scanned directly from the ship with the blue surfaces the viewer sees on the table, and derive the internal structures – tunnels and corridors from the probes – with other colours. |

|

|

|

|

Holotable Hub “Because the casts’ eyelines were working in different directions, I designed several different parts of the interface based on ideas from modern aircraft systems but projected into a futuristic technology – instead of altimeter and GPS readings, we had medical diagnostics on the crew members. If you actually study all the numbers and readings, they all make sense – it constitutes a believable technology.” The scanning probes that the astronauts send down the corridors of the dome, recording the bounces from the beams they send out, are another likely piece of survey equipment the team designed. The characters throw them into the air and let them fly around collecting mapping data for inaccessible places. |

|

|

|

|

Laser Beams The holographics in character Meredith Vickers’ chambers was one of the simpler tasks Fuel undertook, but also one of the most attractive. The Art Department and concept team supplied a beautiful matte painting to replace one of the walls in the room and Fuel, led by Xavier Bourque, built a snow system for it, all done in Nuke. They added small snow flurries scattering through the light, and dimensionalised the cards made for the trees, mountainscape and snow. “We treated it as a window through to another world. The lighting had to be bent slightly to shine on actors and elements and reflections added but not interfering with the DP Dariusz Wolski’s lighting,” Paul said. Words: Adriene Hurst |

|