From pre-production to post, Rushes created motion graphics

for more than 300 screens on set, appearing in 23 scenes ranging

from Q’s lab at MI6 to inside the villain Oberhauser’s lair.

Rushes’ Screen Graphics Monitor the World of SPECTRE

A fascinating side of all James Bond movies is the range of state-of-the-art, top secret gadgets, weapons, vehicles and devices included in the stories. In ‘Spectre’, Rushes post and VFX studio in London designed and created all on-set UI screen graphics the audience sees, showing digital outputs for those devices.

Through 13 months, from pre-production through to post, Rushes created more than an hour of animations and motion graphic sequences, delivered to over 300 screens appearing in 23 scenes – either inside the villain Oberhauser’s lair or in the quartermaster Q’s lab at MI6.

Ready, Set, Go

Because the director Sam Mendes and DP Hoyte Van Hoytema decided they wanted to play back all of the screen graphics on set and capture them live in-camera, much of Rushes’ design and testing work happened during production, when they supervised to make sure the graphics would compliment the set designs and camera set ups, and work as fully interactive props.

The production’s approach satisfied both the DP’s intention to shoot all light interaction on set, and the director’s desire to capture believable performances from the talent. Nevertheless, working alongside the production called for a new approach for Rushes as well, who had to respond to continuously changing demands from set instead of dealing with challenges in post, which is their usual role.

To be prepared, preliminary concept design had to start well in advance of initial shooting, to be prepared for the start of principal photography at the end of 2014. They also scaled up their motion graphics department, MGFX Studio, to tackle largest scenes. John Hill, creative director at Vincent design and animation studio, joined the team as Creative Supervisor to work with Rushes’ team led by Barry Corcoran.

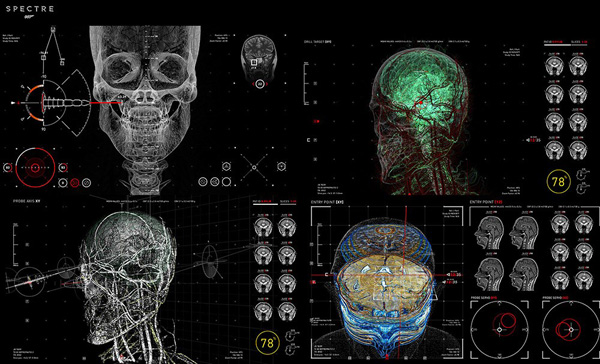

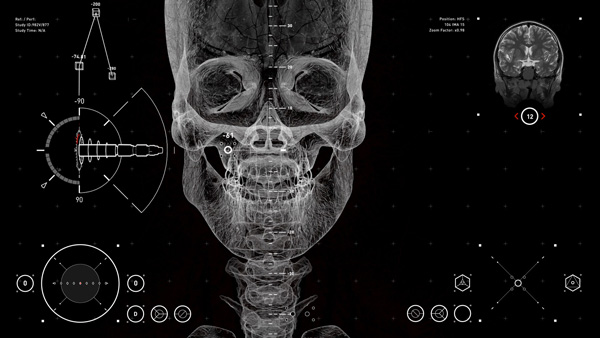

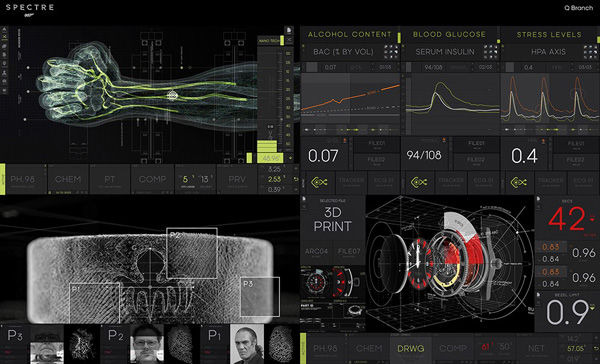

Barry said, “Discussions with the production focused on how to portray systems and software from the near future as realistically and accurately as possible, while staying within the context of the story. More specifically, we aimed for a believable system that could be ready and available to the military. While researching, our head of CG Andy McNamara investigated various scientific developments, including the emerging field of nanorobotics, and gained enough of an understanding of them to discuss the possibilites with the director.”

Military Operating System

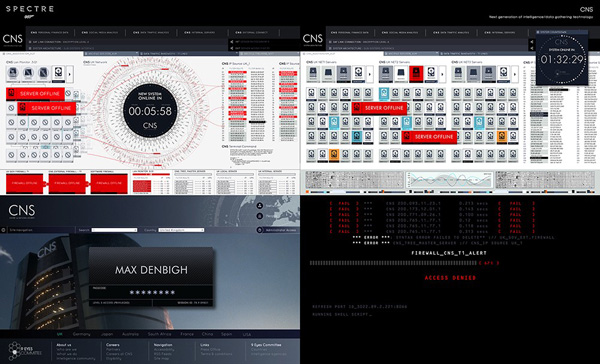

The first task was developing a visual language, displaying intelligent design and functionality that was going to support the dialogue, performances and action the director was aiming for. “From the beginning our design aesthetic aimed to keep this visual language clean and strong,” said Barry. “The director wanted to focus on storytelling as opposed to complex graphic interfaces, aiming to achieve a sense of realism by creating operating systems for advanced military-based data. We referenced existing digital platforms within the UI and UX market, pushing them further to create a new, specifically designed system and interfaces.”

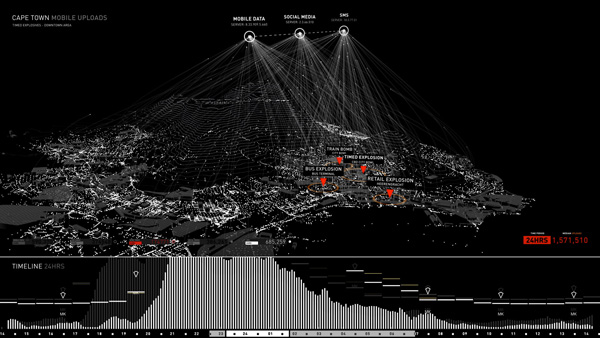

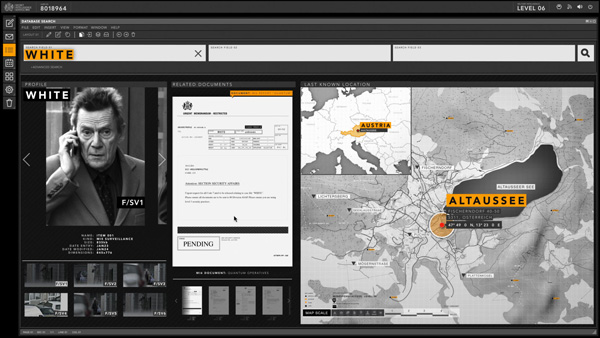

Rushes’ UI systems and tools needed to express Q’s gadgetry in digital form. Banks of monitors showed these as schematics in Q’s lab, and still more screens were used in the villain’s lair to display analytical data, infographics and adapted news footage. John Hill said, “We spent time referencing the interception and collation of metadata used in environments ranging from military intelligence to medicine. This information gave us a good design rationale and a credible premise to build on when creating props for Oberhauser’s lair, the Centre for National Security and Q’s workshop.

“To realise Q’s digital world of MI6 systems and 007 gadgets, we designed a bespoke, modular operating system that would compliment Q’s prodigious mind. Contrasting this was the dark world of Oberhauser’s lair, designed to monitor vast amounts of global news and data traffic. We designed these analytical graphics in rows to compliment the long lines of workstations, tailoring enough variety to populate all of the 130-plus monitors.”

Digital Playback

On set supervision included working with the art department, production designer Dennis Gassner and digital playback supervisor Chris McBride. Pre-vis was created for the larger scenes such as Oberhauser’s lair. As well as helping the director visualize how the screen graphics would play out, the pre-vis gave the on-set playback technicians a better understanding of how to put the scene together.

“As digital playback supervisor, Chris McBride worked tirelessly between us and the production designers on all scenes requiring any digital device that was playing back any kind of footage,” Barry said. “His role involved supplying all of the digital devices on set and managing the digital assets to display inside them - everything from smart phones playing facial recognition software to 4K widescreen televisions.”

Challenges aside, supervising on set for all of the graphics heavy scenes gave Rushes a chance for some creative problem solving and detailed input on the production design. “We supplied loopable video elements to the on-set playback technicians that allowed the director to film continuously. But the more involved, script-specific scenes required the animations we supplied to hit key beats. In those cases, being on set allowed us to advise on the performance of actors and when to hit the beats.”

Consolidated Pipeline

Basing the story’s operating systems that John Hill describes above, on a modular framework resulted in an adaptable, flexible design that could be re-populated and re-tweaked according to directors’ requests, all leading to to a multitude of looks for the UI graphics. Creating specific styles for specific scenes was essential, and many, diverse iterations were created before looks were signed off and artists started populating shots with scene specific designs. This step by step approach allowed all artists to keep within one aesthetic at a time.

Rushes also called on the talent within their CG and VFX departments to give the motion graphics team more options in their layouts. For example, in order to produce realistic news reports of terror attacks, Houdini simulations and NUKE compositing helped achieve photorealistic shots of attacks based on the city. The departments shared a consolidated pipeline, and having everyone working together meant the producers had access to artists with different skills to cover all tasks.

The MGFX team’s graphics work started in Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, with Cinema 4D and Affter Effects for the 3D animations and motion graphics. The visual effects artists’ pipeline was based on Maya and ZBrush, with Houdini for FX, and NUKE compositing. Following the end of initial shooting, Rushes carried out additional post work on over 80 of the screens, including monitors, laptops and phones used throughout the film. www.rushes.co.uk