| Jonathan stepped into production on ‘Sherlock Holmes’shortly after shooting of the film’s plate material had been planned. He helped advise the production crew on approaches to shots from a visual effects point of view, and on overall feasibility. Framestore was awarded 450 of the film’s 800 total FX shots, working 11 months in total on the project with a team of up to 80 artists at its peak stage to release at Christmas 2009.

Environmentally Aware

As important as explosions and destruction, if less spectacular, was recreating Victorian London. When working on environmental effects, the team used the phrase ‘pastification’ to describe the process of taking modern locations and pushing them back into the 1870s. Isolated areas of Victorian London do still exist so wherever possible, they shot scenes on location, removed obvious 20th and 21st century references or hid them with digital props, and painted out wires and telegraph poles.

But whenever the camera made a broad sweep or shot from above revealing a wide area, it was obvious how little of old London remained after the bombing in WW2. The team relied to a large degree on matte paintings or modelling bits of the city and fitting them in. Interestingly, photography was getting well underway just after the Holmes’ era.

Because little changed from that time until the 1930s, London’s early photo records proved invaluable as reference, especially a series of shots taken from the Thames itself showing industrial river buildings and landscapes. “They showed us just how active the Thames was in those times, a working river not a leisure or residential location,” said Jonathan. “By cross referencing the photos with period maps, we could visualize what might be visible from different positions and base our paintings on logical assumptions.”

Day-for-Night

The paintings were made using Photoshop, 8K to 16K wide and typically involved going out to photograph existing buildings and textures to drop into pictures, which worked especially well when the lighting was suitable for making adjustments later. This was important for the day-for-night scenes. For a night sequence on the Thames, for instance, a boat was shot in a small docklands tributary using a carefully set up camera angle going up and over the boat and tracking along it. Then they painted their picture onto some rough geometry that tracked with the camera and could paint in the odd reflections of the lights that would have been on the water. Overall, it was quite a challenge.

Paintings were then projected using Framestore’s proprietary projection manager or Nuke. Nuke was used for compositing reflections. Maya was sometimes used for modelling buildings but also Nuke’s modelling capability was very useful, and could prevent compositors from having to wait for assets to come through the pipeline or go back for adjustments. Framestore found this was a good reason to change from Shake to Nuke recently.

The Baker Street and Piccadilly Circus shots, some river views and others in which the camera moved by quickly all used matte paintings to show London in its former state. Director Guy Ritchie was keen that the environment should not look foggy, historical accuracy notwithstanding, and wanted to portray a new version of old London, featuring luminous colours. Director of Photography Philippe Rousselot had a distinct look that the effects team matched with lots of set references. Everything that looked clean, new and white had to go, as well as trees and smoke.

Looking for Piccadilly

Piccadilly Circus has changed so completely since the 1870s that they actually shot those scenes in Greenwich, where just one building remains resembling the correct, old style architecture and without the hordes of people at all hours of the day. They added a 3D Eros statue and some 2 1/2D buildings. One summer morning at 4am, when it was nearly empty, they did go out to the real Piccadilly to shoot at different heights with a stills camera on a cherry picker, which allowed them to project back onto some Maya geometry and model from the photos.

“We added textures, painted out modern detail, added awnings, adverts and hoardings. All the people were added as 2D elements shot separately on a motion control set about six months later and tracked in despite the different lighting conditions – not ideal and pretty hard on the compositors.”

Jonathan comes from a strong compositing background, with a special interest in lighting rather than modelling or animation. The entire Sherlock Holmes project presented him with quite a few challenges, mainly due to its complexity and large number of assets and 2D elements.

Historic Location

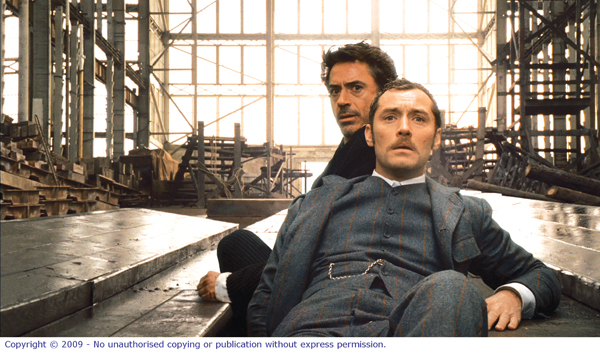

Apart from managing the film’s environment and the establishing shots for the city including nighttime panning shots through the rain, Framestore was assigned to handle two major sequences. One of these, set in a shipyard, was located at the Historic Dockyard at Chatham in Kent, a Victorian era drydock, and required careful blending of CG and practical assets. A 3/4 scale ship’s hull was built of copper, but only one side of it. All action shots therefore had to take place along this one side. Any shots you see from in front of the ship, the other side or of the ship in motion needed a digital replacement.

The three-day shoot was meticulously planned, mainly to work around the cold weather and the fact that water flowed with the tide into the boat shed they were working in, at one point right up to the back of the building. First, they needed to shoot with doors closed and a green screen over the doors with the boat in place, then with the boat removed. Finally, they needed shots with the doors open to capture that view.

Light in Motion

They also shot various elements, high and wide, for when a gigantic capstan comes flying down from above in the climactic shots. The footage from all the shoots had to be pieced together. Unfortunately, they found that the lighting on the different days varied so much the light had changed too much to use the shed itself, the ended up replacing the whole shed with a digital asset, rebuilt and textured from the plate photography, and all done in Nuke to give the compositors the freedom to drop the shed in wherever it was needed to match to other shots.

Because it represented an interior, the environment was fairly forgiving regarding lighting. They could lock off the lighting conditions for the shed and leave them. The moving CG boat on the other hand needed to show movement through a volume of light as it pulled out. The traditional HDRI techniques, usually based on one stationary object, wouldn’t work – they needed to convey the motion of the boat through space. So they lit the scene with Maya point cloud data, which gave them the required volume of light to move through, and on which to register reflections and natural surface lighting changes.

“The copper hull was very shiny and the job had to be done correctly to show it was really moving. But we were very pleased with the result,” said Jonathan. They were also pleased with the large number of assets they were able to put into the scene at any time, from boxes and barrels to the giant chain feed and chain in the ultimate scene with the descending capstan.

Menacing Props

“We simulated the shots with Framestore’s rigid body solver to show all the destruction, and it worked really well,” he said. “The director’s brief for this stipulated that the chain and capstan must have a “menacing character”, and the massive chain had to whip around through the air. It’s a very big chain. It was a balancing act between what the simulation showed us what such a chain would actually do, and animating some additional threat into its behaviour.” The same applied to the capstan, a solid chunk of metal the size of a man, which explains its slight movement from side to side as it proceeds down the length of the shed.

The result is unrealistic perhaps but did look as though it might take Holmes’ head off, and allowed them to jump the capstan over his head, always battling the fact that it must have weighed about 6 tonnes. How ‘bouncy’ could it possibly be? But this element of fun and mischief was a part of their brief, not just in this scene but across the film. Guy wanted to show the characters’ mounting danger, and let them get away with it. So they took a few liberties, made it fun and let the capstan do some damage.

Getting into trouble

Framestore’s other major action sequence, involving the exploding wharf, wasn’t actually in the original script and was only added fairly late in production. “Guy was looking for a way to get the protagonists right into the middle of some BIG explosions somehow. He wasn’t interested in just showing them making a narrow escape at the edge of the action. We followed a careful shoot plan, first shooting the actors ‘dry’ without any explosions at all but got them to react to air mortars going off.” Jonathan remembers watching a sequence of Downey running along and being thrown off his feet, getting up, running further, a fireball goes off, a brick wall goes off, and then another fireball drops down while he defends himself with a tray.

This complete explosions sequence was a significant accomplishment for Framestore’s team and took over six months to finish. It represented a massive compositing job aided with various rigid body solving done in Maya as well as their in-house application. They were also using the Blast Code Maya plug-in for shattering effects and employed the Maya point cloud bleed lighting to add light to the scene that wasn’t in the shoot.

The explosions were shot with slow motion recording on a meticulously planned green screen shoot over three days on a set less than 50m long. The actual location was about eight times as long, but they used moveable green pillars and doorways to provide geometry similar to the live action site.

Compositor’s challenge

The very long shot was captured on a motion control rig, but because it was slow motion and the original photography was shot on a quad bike, the motion control rig would have had to move at about 40mph, too fast to use a rig affording them any lateral movement. Consequently, a slight discrepancy resulted between the green screen explosions and the live action shoot, which they were mostly able to reconcile with Boujou and Match Mover motion tracking software.

“It was a tremendous compositing effort. The team ended up putting in a fully 3D brick wall, built with Maya, because the practical brick wall they’d spent about six hours setting up was a failure. After organizing a ‘green’ battering ram on a track to create the necessary impact, the mortar was still wet and the wall simply collapsed in an uninspiring heap. The 3D wall was detonated with Blast Code.

“Downey’s performance trying to pretend a brick wall had fallen on him was great work, but required a little choreographing to make the experience look threatening though not quite as though he would be killed. That was the challenge – not going too far and losing credibility.”

Emotive Explosions

Several shots needed 3D fire of course, using Maya Fluids, particularly when Holmes is trapped inside a fireball shielding himself with a flaming crate. Abundant 2D elements for flying and falling debris were also created. “This debris was critical in helping a viewer follow the explosions’ motion. Guy wanted you to lock onto an individual piece of debris and follow it slowly spinning toward you or past the camera. The soundtrack helped, dropping to a muffled roar, and the extreme slow motion gave a balletic feel to the movement. Each shot in our sequence had to have bits flying past worth following, to elicit an emotional response to the movement. Only careful use of animation could do this.”

Jonathan is happy with the sequence now although they’d had to keep at it through the last day of production. “Guy had been fairly willing to concede to reality in the shipyard sequence, but the wharf explosions were different. He always wanted to see more drama going on, more bits of debris. ‘There’s a blank space there. I need something in it.’ He understood his own mind, though, and knew he was asking for something fantastical but he wanted a visual, visceral representation. Both he and the actors really enjoyed it, and that whole attitude of fun crept into post as well.

“I could have used another three months to really get the sequence right. FX work is like that, the first 90 per cent goes smoothly but the last 10 per cent takes forever. Some directors get impatient or bored but Guy wasn’t afraid to work through it.”

|

But, as VFX Supervisor Jonathan Fawkner at Framestore pointed

But, as VFX Supervisor Jonathan Fawkner at Framestore pointed