|

On 2 May, Metroscreen held a workshop called ‘The Art of Storyboarding’ with David Russell. David talked to a room full of working and aspiring filmmakers about the history, process and mechanics of storyboarding - that essential, behind-the-scenes ingredient of virtually every production from big-budget feature film bursting with special effects to shorts, TVCs, games, interactive websites and, in particular, animation.

Director’s Vision

When a director starts working on a film, he reads the script and develops pictures of each scene in his mind, and of the story overall. Storyboard panels are the visual language he uses to communicate his vision to his director of photography and production team. The storyboard artist makes the director’s vision a graphic reality, translating the story into images. He keeps the focus on the story and, above all, the action.

What are storyboards for?

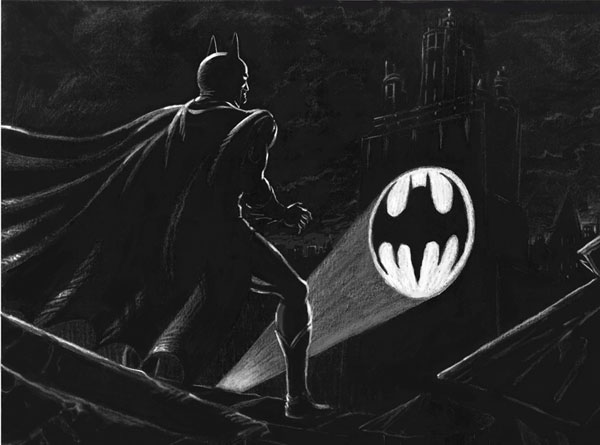

Storyboards have a similar role to comic book panels. Comic panels may not always be an appropriate model for storyboards – not even for the many films being made now based on comic book heroes – but both graphically progress the writer’s story.

Storyboarding shouldn’t be confused with pre-visualisation, although the two departments often work hand-in-hand. When a director briefs the storyboard artist on the narrative of a scene, the pre-vis team constructs the scene based on the boards. If the director gives either department plenty of freedom, the pre-vis supervisors and storyboard artists have to be capable of co-directing.

Boards are the ‘roadmap’ ensuring that the film crew shoots a film’s story according to the director’s intention. It would be a serious mistake for a director to hand his film over to his DP without storyboards. Alfred Hitchcock, for example, relied heavily on his storyboard artist to control suspenseful sequences and direct the viewer’s attention effectively.

Walt Disney had a strong influence on storyboarding and some artists consider him its originator. Storyboarding is certainly integral to animation - while a live action feature may require 60% of its scenes storyboarded, the boards for an animated movie become the feature itself, and are required for every scene.

Influential partnership

A storyboard artist’s work begins at a critical phase of a production. After receiving the approved script, he gives the director his first look at the action of the film and therefore has a direct influence on the look and progression of the film. For example, it’s difficult for a director to mentally plan a dialogue sequence without working it out visually. A storyboard artist can do this for him while, at the same time, keeping the story within the director’s control. As a visual designer, the storyboard artist also guides special effects.

Directors find a useful story partner in the storyboard artist. Some take full advantage of this asset, essentially assigning the direction of entire sequences to the artist. Conversely, other directors can competently think through and dictate each shot precisely to the storyboard artist, who then concentrates on effectively composing and rendering the shots. David said he has actually learned storyboarding skills from working with such directors. Most directors fall somewhere between these extremes, building up a productive collaboration that often improves the scope and power of the script and the director’s original vision.

Narrative rythm

A film’s workflow will run from the director’s concept to the DP and actors via the storyboards, to the editors and finally to post-production, where that may become an editing guide. Therefore, they have to enable everyone to maintain the director’s original focus.

The storyboards often reflect the narrative rhythm of the film as well. The faster the pace, the more boards are required. Certain directors such as Martin Campbell, with whom David worked on the tense, mountain climbing thriller, ‘Vertical Limit’, prefer to elaborately storyboard action sequences, and often refer to the storyboards during the editing process.

Can a low budget movie save money by skipping the storyboard stage? David said that putting in the hours on this graphic roadmap early in production can save time and money later trying to work out shots, wasting footage and the crew’s time on set.

The kinetic frame

Because the boards depict action - people and objects moving into or out of the frame, or toward or away from the camera - a good understanding and awareness of composition is critical. Within each frame, the artist has to pay attention to the setting, continuity, motion and fluidity, and avoid static drawings.

A storyboard needs to work quickly and accurately, and have a range of skills at his fingertips. Knowledge of graphic design, natural and architectural rendering, anatomy and traditional and digital media are all important, combined with a good imagination and, of course, training in drawing, painting, colour, perspective. To contribute effectively to a film crew, he also has to know about camera theory and using the camera as the ‘eye’ for each scene, lighting, VFX design, stunts, and dramatic and comic timing. A storyboard artist takes an interest in the arts and film history, has social and political awareness, diplomacy, and is a good communicator and listener.

In the rough

After an artist has read a film script and been hired, briefings take place between the director, production designer, art director and storyboard artist. The artist flags sequences for storyboarding with the director, views the concept design, and makes initial sketches of the set, location and models. He then prepares some initial boards, or ‘roughs’, for the director to approve or alter.

As the culmination of the initial briefing, despite their name, roughs are actually carefully composed to establish locations for everything within the camera frame, background and foreground, static and moving. It‘s best to work with a written shot list, if available. The actors’ and camera moves are shown with arrows. Some roughs end up as shooting guides, so they need to be accurate, but ideally, the artist re-draws and refines these, usually several times, resubmitting each time for approval, until the director approves a final set of rendered illustrations to distribute to the teams and crew. David advised compiling a booklet of sketches for the DP, showing how to set up each scene before starting to shoot.

Storyboard as Production Tool

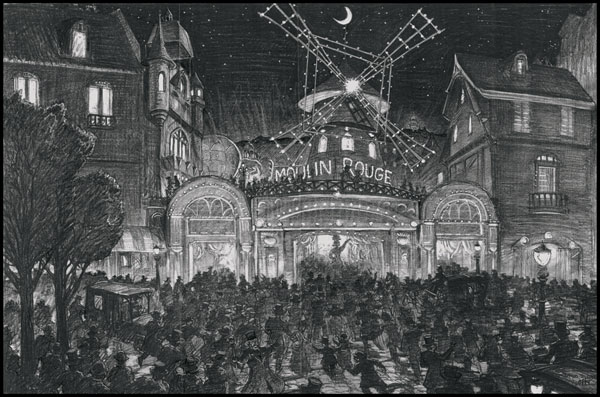

In the earlier stages, a director and storyboard artist may and should spend a lot of time developing the ‘look’ of a film. Even prior to finalising the script the director may ask an artist to make concept illustrations. This can involve research to accurately identify the details of certain cities, buildings or wherever a story takes place, although artists typically have enough general knowledge to draw most settings and locations.

As the artist progresses to storyboards, his notes and drawings will describe camera moves and angles and positions of actors, and indicate motion, actions, human interaction and facial expressions. He needs to show perspective, lighting, transition points within sequences, and action notes, and may even augment the script visually.

Continuity and discipline

The boards should be completed during pre-production, when the director is thinking methodically and can use the boards to strengthen scenes. The writer or specialist may help with the details, but more often the artist is on his own with the director.

While he has to be aware of the physical limitations of filming and cameras, the storyboard artist’s job is more concerned with maintaining continuity, containing the effort put into a film to match its budget and responding to the director.

Boards really become valuable when planning tense, dramatic action sequences. On set, such scenes demand self-discipline from the DP to shoot within the director’s parameters, making sure all set elements and people are where the director wants them to be in every shot. The boards allow him to do this. In fact, very large productions with several major complex scenes involving lots of people and effects may have more than one storyboard artist, handling different shots. Such films rely on continuity staff to make sure all shots work together in the same production.

|

a

a