The Bazmark internal VFX team describe techniques and processes that brought the world of ‘The Great Gatsby’ from a vision to the screen.

The Great Gatsby – Dream Team |

|

A critical factor in the production and post production of ‘The Great Gatsby’ was the Bazmark internal VFX team, a group of concept, visual effects and post artists who worked out of the production office at Fox Studios in Sydney. Among its main purposes was to give a skilled group of artists direct access to the director Baz Luhrmann, producers and the set without the extra layer of the vendors’ producers in between, thereby allowing certain post production decisions to be made more rapidly. The unit began to take shape in mid-2011, two or three months before principle photography got underway, which ran from about September to December 2011. Back during the earliest trial stages, the film’s VFX supervisor Chris Godfrey asked Tony Cole, 2D VFX supervisor and digital colour timer, to help test and decide on the best way to capture the extensive green and blue screen shots the movie would require, in terms of material to capture it on, the best saturation to use with the RED Epic cameras and other options. |

|

|

Following that initial test period, executive producer Catherine Knapman and production manager Alex Taussig contacted Tony Cole about designing a pipeline for capturing the rushes and processing the whole project, through post and visual effects to the digital intermediate. Once the project was green lit, Tony, Chris Godfrey and VFX producer Prue Fletcher started to form the Bazmark internal VFX team to work alongside the production at Fox. Colour DecisionsA primary goal for both Chris and Tony was controlling the colour in the footage before shots went out to the various visual effects vendors, as a means of controlling what came back to the production in preparation for DI. In the past, vendors tended to use a variety of different colour management systems which had caused delays and complications during quality control. Furthermore, they were aware that the fact that ‘The Great Gatsby’ was being shot natively in stereo would add colour variations of its own. “The reflected eye typically does not match the primary eye, usually the left eye. Therefore, because VFX vendors need to colour balance and align the images before working on them, all using different techniques and degrees of thoroughness, Chris and I decided to take care of all geometric and colour balancing and correction before sending any shots out,” Tony said. |

|

|

They were working with approximately 300 TB of R3D data by the end of production, and making it all accessible on line. Each day of the shoot, the crew would deliver that day’s media, which they would load into their Mistika image processing system to synchronise and correct the stereo rushes. Doing this themselves at that stage allowed them to proceed treating and handling the two streams as if they were one, with a single EDL. Tony said, “Where this really paid off was during the compilation stage later on, when it saved us a great deal of time and, therefore, money because we didn’t need separate EDLs for left and right eyes. “Once colour and geometric synching was done on the Mistika, we could essentially forget about the fact of the stereo shoot - providing footage, handling and referring to it as if both streams were exactly the same. For example, if a VFX shot involved green screen the vendor would only have to pull one key with no need to apply two different keys on the images comprising a single shot.” Handling the RushesAs soon as the rushes arrived, Tony’s team of about 40 artists could fairly quickly balance the colour and geometry on every shot – not rendering the adjustments but storing the corrections as data. This way, when the EDLs eventually came from editorial for the VFX pulls, half their work had already been completed. They changes only had to be rendered out as floating point EXR images to send to vendors with colour and geometry looking very close to the way they should. |

|

|

Further to these preliminary corrections, Chris wanted to ensure that the colour was consistent within scenes and between separate shoots. The party sequences, for example, were shot over a two-week period at several locations, and some driving sequences were shot over several days. So every VFX shot and element shot was accompanied by a Nuke script that Tony wrote – serving as a colour grade to apply to all components involved in any given sequence. By the end he had written about 2,000 of these scripts. “After rendering out the EXR files, the vendor would then import them into Nuke to generate the ‘colour correct’ scripts for each shot,” he said. “We sent this material first as a pipeline test package to the vendors – shots plus instructions on how to apply the scripts and on the rendered DPX sequence they should return to us. If their test passed, they could proceed and start completing their shots. Due to the volume of material we had to get through, at that point we were pretty stringent about quality control. The whole idea, after all, was to avoid wasting the director’s and colourists’ time on correction at the DI and grading stage, and to give Baz control over looks in the creative grade.” Creative ControlThis was the goal – maintaining control, monitoring consistency, while allowing as much creativity as possible for the production designers. It took a while to settle on this workflow and it was not a quick fix, but it worked. |

|

|

Once post and visual effects were underway, Tony’s role on the Bazmark effects team shifted more toward 2D supervisor, working with VFX art director Daniel Cox who was setting the looks and style of the environments, and Clinton Downs, overseeing 3D work for several of these settings. With Tony’s small 2D compositing team, they figured out how to make the work of all three departments come together. “The team had fairly limited render capacity and had to work efficiently so, based on our decisions, I built compositing templates for all of my compositors so that the information generated by the art direction team and 3D artists could be applied within a 2D world, using the template script,” explained Tony. “For example, Clinton had designed a camera track for every shot as well as built, rendered out and shaded a 270° shot of New York roughly covering Central Park to the Queensboro Bridge. The scripts allowed the compositors to import the cameras at any spot, point them at Clinton’s geometry and from there would only need to integrate the blue screen imagery on top of the backgrounds existing in the templates. All detail was live and editable, however, templates answered the inevitable questions and uncertainty about where certain images might work in 3D space, positions of assets, suitability of skies and so on.” |

|

Compositing DataA principle sequence that the Bazmark team handled was the main characters’ climactic confrontation in the Plaza Hotel suite. From the rushes, Tony knew what was going to be visible from each window. Between pieces of source and stock footage, Daniel’s resulting conceptual matte painting covering the same wide New York area, and Clinton’s 3D geometry and camera tracks, Tony could provide the compositors with a lot of data in his templates about how the completed shots should look, especially since they received consistent lighting information for a given time of day. Although the director decided to change the time of day for this sequence to several hours later than originally planned, Clinton could update his files to reflect the differences in detail that the altered light revealed. “Dan’s artwork was also used to help flesh out and add detail to a number of areas and views. His paintings were quite accurate and could be projected fairly successfully onto the geometry – some have even held up through post and appear in environments in the final matte painting seen in the movie,” Tony said. |

|

|

Because previs was still being produced for shots up until six weeks before delivery, the direct access this team had to the director was essential if the last minute decisions were going to be carried out in time. Furthermore, Chris Godfrey was also working in the same office as the production and this team, making it more possible to continue evolving shots and sequences. He could go straight from a discussion with the director to the VFX art director and 3D and 2D supervisors. Camera DesignIn particular Juri Fripp from the 3D team, dedicated to camera work, would design camera moves based on an idea from Chris and Baz about two weeks from a shoot and then ensure that these moves appeared in the film. This meant that at least for the studio shoots, previs and cameras could be developed in the office, taken directly to the set to discuss them with the DP, take measurements and so on. Pre-viz’ing on the fly in this way was an unusual advantage. Daniel Cox, Clinton and Tony could all go on set if required as well to get their questions answered quickly. Consequently, the previs often matches the movie very closely. “Camera moves become more critical to VFX departments on a stereo production because of limitations the crew have on set due to the size and weight of rigs, for example. It’s good to discuss allowances for post cameras moves to overcome these issues,” Tony explained. |

|

|

“In a similar way, I had colour discussions with the DP Simon Duggan because the RED Epic can present data in such a variety of ways. The RAW format reveals very little when viewed on its own – it needs a DIT on set to set the colour balance for viewing which, if done independently, is unlikely to match the final looks. I wanted to explain that colours introduced for editorial purpose weren’t necessarily going to apply later on. Grading aside, VFX teams work in a linear colour space, which means they start again with basically RAW images, without any changes to contrast, to allow a uniform balance across all of their shots. It’s worth advising the DP of this fact, who can end up feeling that his images have been spoiled or broken in some way.” From Pre-Viz To Post-VizWhile Chris Godfrey and Prue Fletcher were setting up the VFX unit during pre-production in mid-2011, 3D supervisor Clinton Downs spent three months working on previsualisation and setups for the shoot. He then returned post-shoot in early 2012. “At that point we shifted our focus from pre-viz to post-viz,” he said. “We churned through hundreds of purely blue-screen shots to aid in the story telling as the film was being cut together. This eventually focussed on shot finaling, as the unit was responsible for delivering around 470 shots in the final film.” |

|

|

Clinton feels that, for Chris and Baz, any effort put into effects was always about the story and, given that the ‘Gatsby’ world was essentially synthetic, Baz was focused on ensuring believability was retained at all levels. He said, “The main effect just happened to be a CG New York City circa 1922, and so the story hinged on its realism. That approach extended to every image on frame. At the start Baz told us, ‘There are no backgrounds', which was to say, the effect needed to serve the story at every level, in every detail and in every thing we created. “A stand-out challenge for the entire VFX unit was balancing the demands we faced, covering nearly every post process involved in delivering the film. The CG team began in pre-production with pre-viz, continued during the shoot with tech-viz, following the shoot with post-viz, and carried on with final shot delivery. Within the one team of artists, many crossed disciplines between all phases.” Virtual SetsThe Bazmark VFX team worked hand in glove with the internal Art Department. To reinforce the look of the world they were creating, the walls of the offices at Fox were littered with photos from the period, as well as the Art Department’s concept art. The role of CG for ‘The Great Gatsby’ was unusually significant. “So much of the world you see in the film was created entirely by CG artists, and so many of the sets, massive themselves, were extended with the aid of CG. Gatsby's ballroom required a full CG ceiling extension to complete and some shots within the mansion were completely CG,” said Clinton. |

|

|

The 3D CG software pipeline was based on Maya for modelling, texturing, lighting, animation and effects, plus Mudbox for some of the modelling as well and PFTrack for tracking. Nuke was used for compositing and the rendering was done with mental ray. Throughout the story many key scenes feature extensive camera moves, such as the first time New York City is revealed to the audience, or when the viewer flies across the bay from Buchanan’s mansion to Gatsby's. “Designing and directing these shots came down to pre-viz - first, to ensure Baz's vision would be conveyed but also to provide reference for how the shot will be created. In many shots, that second aspect was critical to how Chris Godfrey approached the technical shooting requirements for a given shot,” said Clinton. “Once Baz was happy with some pre-viz, we often created a tech-viz document to hand to the production crew. The document specified the lens to use, height and distances between the camera and set pieces, and furthermore became a guide for how the sets would be constructed to ensure, for instance, that a camera move would be possible within the confines of the stage. 3D artist Juri Fripp was the main person on tech-viz, and Cameron Sonerson oversaw the pre-viz.” |

|

Shot PlanningWhile Clinton didn’t work on set himself, Juri Fripp went on to play a critical supporting role to Chris Godfrey. Because thorough shot planning is essential when shooting a project that relies heavily on complete, digital environments to be created in post, Juri was on hand to provide a full array of detailed tech-viz setups to prepare for each shoot day. The setups usually included information on shooting angles, distances, lenses, lighting angles and so on, generally derived from the VFX unit’s previz work. Clinton said, “An interesting kind of 'virtual reality' tool that emerged from this work allowed Chris and Baz to see the world beyond the bluescreen on an iPad, live on stage. For example; we had only a partial set build for Nick's bungalow, and understanding the height and location of Gatsby's mansion next to this was practically impossible. With the on-set tool, Chris could stand in a pre-determined location, hold up the iPad, and literally pan around to see the exact location and size of Gatsby's castle, all while changing the virtual lens used to view with. This proved extremely useful in staging camera angles between the real set pieces and the virtual ones.” The set surveys were another major focus of data capture. The on-set data wrangler Felix Pomeranz was also very skilled in set survey, so whenever he had a moment to spare, he would survey the tracking markers from the set, which were later used to great effect when camera tracking and lining up the digital sets. |

|

Vision and AccuracyThe fact that ‘Gatsby’ is a stereo film affected the 3D team’s processes substantially. In a single camera production, for example, set extensions outside windows, such as those surrounding the Plaza Hotel suite mentioned above, can typically be managed with compositing techniques such as 2D camera tracks. “Yet with stereo, most of those tricks aren’t possible and a 3D team has to take on the work. One extra advantage is that by forcing a lot of those shots through CG, we achieved more realistic camera moves, and the world is placed far more accurately. So, indirectly, I think the film’s world has a greater sense of reality,” Clinton said. “A further challenge from the perspective of the CG artists was upholding the spontaneity of Baz's ideas through a process that can span months. When Baz expresses his vision for a scene, a shot or just a moment within a shot, it's basically an instinctive reaction, and typically conveyed in words. Taking those words and converting them into an image on the screen, while maintaining the original vision through that process is very challenging. Art department play a large role in this process, as capturing the vision in a rough conceptual way first is really important. The VFX art director Daniel Cox was involved in the unit early in the production schedule, mostly during the post-viz phase. Consequently, his concepts helped the 3D team assemble a first version of a scene relatively quickly. |

|

|

Clinton said, “At one stage we were post-vizing a scene that required a night-time rendition of Times Square seen from the top of a nearby building. Collaborating with the CG artists, Dan painted an extended matte painting that allowed us to place a CG camera in Nuke, and have the correct view out across the matte painted city. At about the same time we delivered shots for the first trailer. One of Dan’s concepts became the basis for a matte painting we projected in Maya with Nuke onto some basic geometry, saving a lot of time achieving a final result.” Shooting at 5KThe internal VFX unit found shooting at 5K was incredibly useful in a lot of the re-projection work they handled, and in turn helped save time and money. For example, Gatsby's garage interior was a half-build, with one side left as blue screen. “For a couple of shots, we needed to replace the blue with the interior of the garage,” said Clinton. “Ordinarily, we would construct this from stills taken on set by the VFX supervisor but in this case, images with correctly placed set lighting hadn’t been captured. Instead we sourced some footage from between takes that showed the section we needed with the correct lighting. After assembling a series of suitable frames, we successfully created a totally photo-realistic set projection.” Further to this procedure, VFX work was sometimes required on sets that had not been slated for effects, which meant proceeding without the usual set data. For example, Gatsby introduces Nick to Wolfshiem inside the barber shop, a nearly complete set build, beautifully detailed and historically accurate, with a blue screen outside the window. The initial intention had been to simply extend the exterior environment into a populated neighbourhood. Stills had been captured of the set - but without lighting data from the shoot. |

|

|

By July, some extra dialogue was required from Nick for this scene but because the actor was back in LA, the new footage was shot against a blue screen only. The technique chosen for the set rebuild that matched the existing footage the most closely was to build geometry to match the set, and project filmed plates back onto that geometry. Image Modelling“Again, we sourced suitable frames from the shoot, but instead of simply creating a re-projection, we used them for set reconstruction as well, with image modelling software called PhotoScan, which uses a series of photos to generate a 3D mesh. From this, we accurately mapped out the environment in 3D space and performed the required work,” said Clinton. “Our approach was similar to the garage interior – modelling some geometry to match the filmed plates perfectly and searched footage from the original shoot for plates that would work to rebuild the set. Once found, we sourced the 5K plate, performed some frame blending to remove grain and commenced repainting the plates to suit the re-projection, including textures. “The process recreated around 40 per cent of the set in a completely photorealistic way. You could essentially 'film' the CG set to match the original perfectly, as we had used the filmed plates for texturing our models, placing the models themselves based on survey information derived from our tracking software and PhotoScan. A major bonus of re-projections is that all you need are models and some textures - there is no rendering step - so you can export these set builds into tools like Nuke and really take advantage of your images. |

|

|

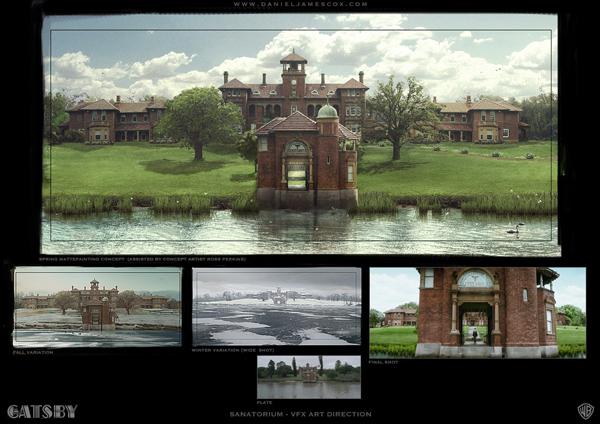

“The team also used Photoscan to replace traditional LIDAR scanning for some props we needed to digitise, but the process doesn't replace the role of the modeller or texture artist because the mesh it generates it not very well ordered and nor are the textures. Nevertheless you can remodel fairly accurately from the information it gathers, and also re-texture more quickly because the software provides points in space for each of the photos taken, making lining up your CG camera for further re-projection easier.” Visual ChallengeWhen Chris contacted VFX art director Daniel Cox about ‘The Great Gatsby’, Daniel jumped at the chance and soon got to work on several visual challenges that had yet to be solved. These included key decisions on how to depict New York and the overall style of the city sequences, the sanatorium featured in the bookends that Baz devised to tell his version of the story, Gatsby's mansion, a graveyard sequence and more. “My focus wasn't so much on the details, but was more concerned with getting the right mood and lighting scheme into the paintings, which I made mostly in Photoshop, knowing that eventually the vendor would add the actual detail. It’s all about working in broad strokes and giving Chris options that he could take to the production designer Catherine Martin and Baz,” Daniel said. He worked with concept artist Ross Perkins, who was working his way through a master shot of the Valley of the Ashes. |

|

|

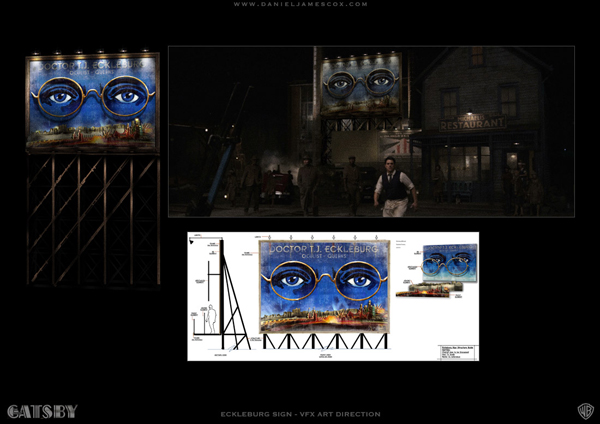

“An example of the way I would approach decisions on sets and props is the billboard of Dr Eckleburg’s eyes, a prominent storytelling feature in the Valley of the Ashes. Catherine Martin and her art department had designed the sign but hadn't yet incorporated it into any plates. The night lighting hadn't been figured out, or how much rust and weathering it should have. When Chris briefed me on his initial idea for the sign, Ross and I devised several ideas for the sign frame and how it could work. Then I worked with Clinton on the 3D version, lit it and placed it into a few plates for approval.” Clean PlateAnother setting was the sanatorium setting. Chris had shot plates of Rivendell in Sydney as the basis for the building, and also done a still shoot. The art team supplied some conceptual art, forming a good guide to work from, but the grounds of Rivendell are covered in massive trees. “I had to create a clean plate of the main building and its wings and then create seasonal variations - spring, autumn and winter - which Ross assisted me on,” said Daniel. “The winter shot was to be used in the opening sequence, so I gave Chris a version with the camera pulled back further than the initial framing, starting the shot with a move across the frozen lake, which I was happy to see made it into the film. For the second trailer, I worked with Clinton and his 3D artists on the matte painting as well for the spring shot. The final version needed moving trees, so it was outsourced to RSP for the final shot you see in the movie.” |

|

|

|

A number of smaller sequences like the wedding scene had to be finalised as well. Chris had shot blue screen plates of the characters on the steps of a church, but nothing else had been sorted out. Daniel put together several different concepts, both outside and indoors, which were sent to Catherine and Baz. He gave these a high contrast finish, referencing the classic noir look of ‘The Third Man’ and ‘Touch of Evil’. “For the speakeasy, Art Department had supplied great period reference, making it fun to piece together the correct look for the era around that area. But the biggest challenge was the Time Square material, circa 1922. Again, I was supplied Baz's top selects from a fantastic library of period photographs, showing me the look he wanted. Of course, all of these photos are in black-and-white so I had to decide how much colour to add, what that colour temperature would be, the amount of light pollution and so on,” Daniel said. “I was also supplied the Arrow Collars logo from the production design team, which would figure prominently in the shot. Clinton supplied me the camera and block model for perspective and rough geometry of a low poly building, and then I painted up the signs and atmospherics. It was a bit like putting together a puzzle without seeing what the final image was.” |

|

|

Geometry ProjectionsThe Sayre Hotel view overlooking Times Square required a higher camera and a large panorama that the team could use in 3D for complete coverage of the view from the garden restaurant. Clinton provided renders, which Daniel would paint over, and Clinton would then project them back on. Another large sequence was the view from the Plaza Hotel. Again, Clinton and his team output large block models for Daniel to paint over, referring to period reference to find out what buildings needed to be where, what they looked like and so on. He made a freehand painting of the Queensboro Bridge as it would have appeared in 1922, and trying to deconstruct how much foliage Central Park had at that time. He completed two versions - one lit for afternoon, and one lit at dusk. Daniel’s work helped with pre-viz in a general way. For example, for the cab ride to Gatsby’s house he painted rough concepts of city, working out the views towards the ocean and the pier, the wide shot of the Valley of the Ashes and so on. He said, “For this kind of conceptual 2D work I use mostly Photoshop CS and Corel Painter. I use Painter when the images are at the earliest conceptual stage, and don't need to be refined. I try to paint them using photographic values, but don’t worry about brush strokes. For these images, I tend to use broad strokes and knock out several versions to show Chris, especially when he only has a vague idea of what he wants to do. I'll try several different versions using different colour temperatures, based on the values and hues present in the plate.” To read more about post production and VFX for 'The Great Gatsby' see Digital Media World's feature here. |

| Words: Adriene Hurst Images: Concept frames courtesy of Daniel James Cox. Production stills courtesy of Warner Bros Pictures. |