|

By Adriene Hurst

Supervising Animator Scott Clark and his team’s work as animators got underway when Director Pete Docter’s story was pinned down, came to fruition and everyone at Pixar knew they had the story they wanted to make a movie about. They also began to want to see how the characters would look and how their personalities would develop. The script had been written and storyboarded, and Scott could watch a sketched comic book version of the movie in real time.

PULLING STUNTS

Character design was carried out in collaboration with the art department, who design the physical looks of the characters, and the characters group, who build the models and articulate them. During pre-production Scott and the other animators would have spent time interpreting the art department’s drawings and designs, and decided how the characters would move and deform. They could then advise the characters group on the controls for each character and explain what they would need to move and pose the characters the way they envision them moving and acting.

Still in pre-production, at the modelling stage, the modellers articulate the characters using proprietary software similar to Maya, and the animators work much as actors or stunt men work, plotting and acting out all the moves and stunts the characters will need to bring the story and their personalities to life. Starting with the basic models, they use their own specialised type of proprietary software to animate the sequences.

STORY IN MOTION

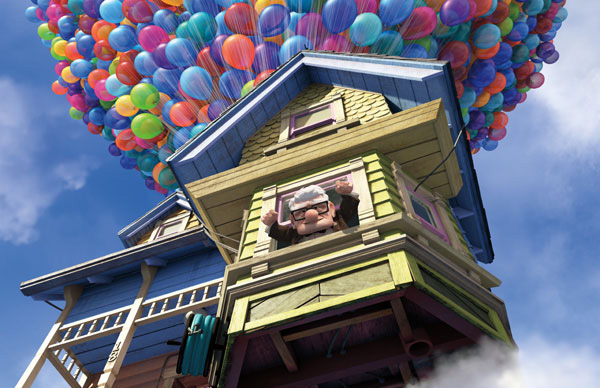

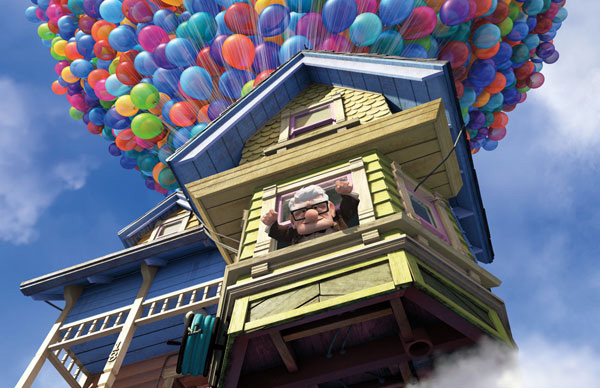

As the movie’s ‘actors’, Scott and his team were not concerned with animating objects like the balloons, the special effects or the wind blowing though the leaves, but focussed on the characters themselves. During dialogue sequences, they worked with the recorded voices and fill in the body language - physical actions, gestures, emotions and facial expressions - to match them. During pantomime sequences that have no supporting dialogue, they convey the storyline through movement.

The animator’s thought process is much like an actor’s but in slow motion, very slow. It takes weeks to produce seconds of footage as they tell the story underlying the dialogue by revealing the character’s inner motivation and thoughts through animation.

Scott Casts each part in the script to members of his crew according to their talents and strengths. The dogs went to animators with a talent for portraying fast, physical action. The protagonist Carl needed a keen observer of sensitive personalities experienced with older characters. Cartoony roles went the comic animators who could make people laugh. Many animators are also good actors who can express emotions that the audience will identify with. The mix between emotive ‘acting’ and graphic physical action is up to the individual animator.

INSPIRATION

Typical source materials and clips come from video references, inspiration from other movies, items found on Internet or something funny observed from everyday life. For example, Scott’s own dog served as inspiration for the leading dog character, Dug. Both are obsessed with squirrels, which never fail to totally distract them. “Because they work in the way that all actors do, observing and re-interpreting found references to inspire emotions and actions that audiences identify with, animators may be called introverted actors. A good performance from an animator feels like it’s happening for the first time as the audience watches it, not made up or invented but happening on screen,” said Scott.

He pointed out that building such a character is not a matter of collecting actions, expressions and gestures, which is closer to the way characters are created for games with stylised sets of movements. “That’s too easy. Animators are using computers but hand-crafting stories by animating the characters using many of the same techniques animators used to create the first animated feature ‘Snow White’.

CARTOON TO HUMAN

“They are still constructing performances to a flat screen, even if the final movie is in ‘3D’. It’s still a proscenium for the audience projected to that camera, leading the audience’s eye to where they want it focussed, depending on which actor is more active, the design of the poses , the characters’ appeal, and also on caricature. Not trying to be too realistic, they create believable performances that reach the emotional core of the story.”

Carl was a challenge as a character, starting from the artwork stage. The art department’s drawings were very geometric, with a virtually square head, and simple, ‘cartoony’ shapes. Simultaneously, the animators knew they needed to somehow make him soft and fleshy before he would be believable because he was a human being. Trying to meet these contrasting demands made it difficult to make Carl’s hard edges read as soft. To take his design too far in the realistic direction could look grotesque and not be subtle enough, tied to irrelevant details like wrinkles, nostrils and nose hairs. He had to be appealing, remain cartoon-like and fun. They had to find just the right level and type of realism to make the audience believe in him but still keep him basically geometric and simple. In short, a caricature of an old man, more emotionally real than physically real, was their goal.

FLATTENING SPACE

The 3D presentation of the movie ‘UP’ was not an issue for Scott’s team or, in fact, for any of the artists’ departments. A separate group of technicians joined the production at the end and rendered the footage set one eye-width apart to create a stereoscopic effect.

“At a play performed live, no one has ever needed 3D glasses to watch the action in stereoscopic vision. There’s nothing new about watching a performance in 3D. Nevertheless, the actors on stage are actually presenting themselves to an invisible fourth wall, the proscenium, and staging themselves to a flat space. The set design is cheated to become a little flatter than realistic architecture would permit.

“We’ll always be cheating and flattening space even if we do convert to 3D, ironically. So it didn’t really affect us at all during the production and, frankly, I wouldn’t want it to. I wouldn’t want to make a choice whether or not to plan something to move straight at camera just for the sake of a gimmick, as in the old 3D ‘B’ movies. What is should do is allow a movie to be immersive, without becoming a distraction itself.

ANIMATED WORLD

The only inanimate objects Scott’s group worked on were those that the characters interacted with physically, such as Russell’s backpack. “The software we use has a script to figure out how all the paraphernalia hanging off the back of it would jangle around, for example, and we would hand-tweak it. We’d separately animate the house and the hose hanging off if it. But the thousands of balloons, the hair on the heads, the cloth – complex objects or material that a computer could mathematically figure out better than we could would be left to the simulation and effects TDs and animators to work on.”

Scott and his colleagues all possess a background in drawn or computer animation in school or university. Some, more specifically, specialised in stop motion. “The computer has made it easier for people to try out animation techniques, but that is not the only way to learn about it,” said Scott, who studied Illustration at Rhode Island School of Design in the US and first pursued animation for some special projects he completed there. He learned computer animation after he had started at Pixar, 13 years ago. “Design, movement and composition principles do not change. Computers are only a method of delivery to the screen. Almost anyone can learn software. You need to ask yourself, ‘What can I do with it?’”

KNOWING WHEN TO STOP

This film was Scott’s second opportunity in the role of Lead Animator. He says he’s always learning from the movies he works on. ‘UP’ taught him that “less is often more”, and simplicity can often be beautiful. “This movie’s design is based on simplicity, and required knowing when just enough detail has been added and then stopping. Too much movement or overanimating the shots often made them less interesting. In some cases, we took out actions and were better able to get to they core of the scene more quickly to find something human and truthful in it.

“For example, an early scene when Carl descends the stairs on his automatic chair in a fairly long shot becomes funny because of what is not there. It was tempting to put in extra eye blinks and small movements like scratching his nose,” Scott said. “But in each case when the actor tried to these actions out, the result was too much. So we just left him in the initial pose, with just enough shake in his fingers to make it believable, and left him alone.

COMEDY VS TRAGEDY

That treatment helped established Carl’s personality – place him in a pose, make him grumpy, blink his eyes once – and that would be Carl. “A lot of animated features these days are full of whacky, crazy creatures jumping around, firing jokes at the audience. It can be fun, but also tiring. Without a sense of tragedy to offset the comedy, there’s no fun left. Maintaining simplicity in the sequences allowed just enough of the tragic element to remain.”

‘UP’ was a challenge but also the film Scott has had the most fun with in his career with Pixar so far. He likes working with the director Pete Docter, and felt privileged and fortunate to be making a film about an old man, with sides of life and humanity to express that aren’t often seen.

GOOD MISTAKES

Creating the dogs was not the least part of the fun. Figuring out the dogs’ characters from real dogs was an excellent experience. Scott found the idea of having them ‘talk’ and speak their true dogs’ thoughts through the mechanical talking collars was a great device and appealed to his imagination. He had worked to avoid letting them come across as anthropomorphic dogs and to make them caricatures of real dogs.

Scott has also spent the last ten years teaching classes on animation and film at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. He’s had to retire from teaching this year, but will return to it. He appreciates the students for the opportunity to learn from the ‘mistakes’ they make before they learn all the rules.

|