A venture between Monash University’s Faculty of Arts and Faculty of Information Technology is

helping to preserve the history of Australia’s Indigenous population through animation.

|

|

| When English ships first arrived in Sydney Cove 222 years ago, 250 languages were spoken by Indigenous Australians. Now, less than half remain. Through the use of 3D animation, researchers are working to recreate the dreamtime stories of the Yanyuwa people, located on the South-West coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria. Currently, only a handful of elders are fluent in the language, the last custodians of ancient songs, stories and customs bound up in the vocabulary.

For the last three years, postgraduate researcher Brent McKee and 3D Animation Team Leader Dr Tom Chandler have worked to bring these dreamtime stories to life. This year Brent has been joined by artists Chandara Ung and Michael Lim, to form theMonash Countrylines Archiveanimation team. It may be difficult to quantify the success of the project, but the response and involvement from the Yanyuwa community indicates that it has been well-received and awareness of the cultural issues has improved. Even more encouragingly, four additional communities have expressed their interest in becoming involved in the project. Scriptwriting |

|

|

|

| To accompany this documentation, the Yanyuwa atlas has maps of all the Dreamings and markers to indicate important landmarks or where important things happen or where are. “We’re lucky that John has such an in depth knowledge and understanding of Yanyuwa culture and that so much pre-vis work had been done prior to animating. However, John is not the final authority on the Yanyuwa Animations,” Brent explained. “We must always get permission from the Yanyuwa elders throughout each step of the process, from screenplay to final production, either by a quick phone call to Borroloola or sending work on DVD or via email to the local Sea Ranger station.”

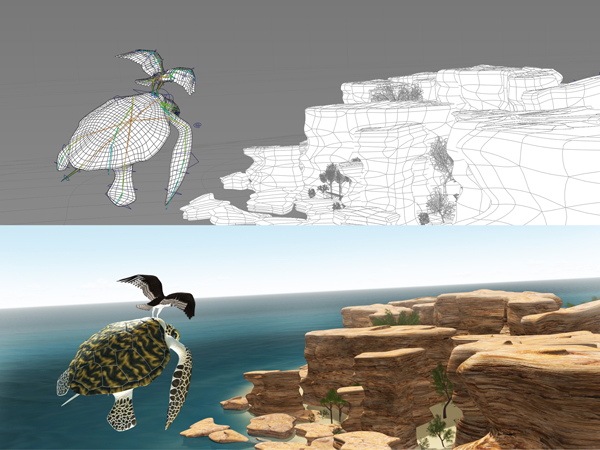

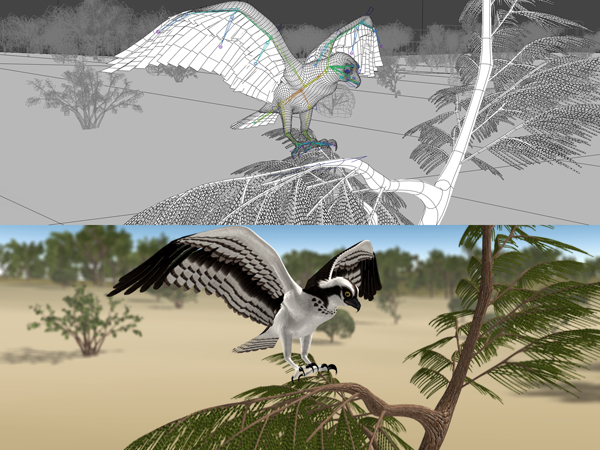

The first series of animations were recorded fully narrated like campfire stories, which is how John had scribed them as the old Yanyuwa men had told the stories to him. For the latest animation, ‘The Sea Turtle and the Osprey’ [Wundanyuka Kulu Jujuju] Brent spent about three weeks rewriting the Yanyuwa campfire story into an action and dialogue-driven story, and sent the English version to John who rewrote it in Yanyuwa and sent it to Borroloola for the elders to proof. With a few corrections it was returned and production began. Storyboards and animatics “First we go through the script and dot point out events and important information. We then draw classical storyboards, with action, dialogue, camera angle and movement. The boards go into a timeline in After Effects to work out the timing for each shot, as the first animatic. Using static characters we construct each scene in Maya, finalising timing, camera angle and movement. These scenes are again put into After Effects for the final animatic. From these animatic scenes, the static characters are animated and landscapes built into the scene.” According to Brent, a number of influences affected the looks of the animations. The Yanyuwa people wanted to avoid heavy stylisation or a cartoon look, preferring elements to ‘look how they are supposed to look’. “To me this meant realism,” said Brent, “but we didn’t have the budget, team size or computing power to pull of any intense photo-realism. We settled for a ratio of 70 per cent realism and 30 per cent stylisation or simplification, with the main focus on the storytelling. But the look also had to be specific as we are dealing with real places, animals and trees - crow had to be recognisable as a crow. |

|

|

|

| “We use a large range of reference material. At our office at Monash University in Caulfield we have access to amazing books to research Australian flora and fauna and use the Internet as well. A great website by David Attenborough, www.arkive.org is basically an online encyclopaedia with photos and videos. Plus, watching hours of films and animations a week is pretty good inspiration for extra detail.”

Yanyuwa Country “Chandara Ung, our lead character artist, for our next animation has been modelling and rigging a Groper fish. He went to the fish market early in the morning, picked out a fish that closely resembled a Groper, took it home and dissected it. We mainly use Maya for modelling and Photoshop for texturing. We are starting to use Mudbox more frequently now, which we can use for all three.” Because most of the character textures are digitally painted in Photoshop, they collect a huge quantity of reference images for texturing characters, mainly from books and the Internet, but don’t use many photo-referenced textures for animals. “I find it easier to paint directly onto the UV sheet in Photoshop, or onto the creature itself in Mudbox. We haven’t experimented much with fur yet but I’d like to in the future. It adds a dynamic to a character that painted textures can’t.” Animal Animation |

|

|

|

| “Our main real world reference for character movement animation was Arkive.org where there are a large number of video references on how birds fly, how turtles swim and walk, and so on. Seeing how other animators have animated animals is a big help as well, for timing and exaggeration of movement. You can also find a lot of cool stuff on YouTube to help with animal movement,” said Brent.

“There is a natural curvature to the movement of every animal, a fluid motion. Once you understand the basic movement of an animal, you can play around and exaggerate certain things. You know when something looks wrong, and as animators we just tweak things till they no longer look wrong. Birds, for example, don’t all move the same way. You have to take size, weight and wingspan into account. A big bird will take fewer wing strokes than a small bird, with slower repetitions. Sometimes when things look just right for an animation, they no longer look like the real thing, and if you tweak it to look more like reality, it no longer looks right as an animation. The key is finding the balance.” Kung-Fu Flip Camera positions were dictated by what was happening in frame. Brent tries to put an observer’s perspective into each shot. Depending on the action in frame, he considers the best way to view that action. “Where one shot leads into another, both need to be at similar angles so that the view doesn’t jump too much. Also, depending on the pace of what is happening in the story at the time, I generally do slower, longer shots for establishing a scene or fast, swinging movements for action scenes.” Maya was used for both character and camera animation, rendering with Mental Ray. |

|

|

|

| Sky, Land and Sea Fortunately, extensive research has been done on the landscape, seascape and vegetation of the Yanyuwa country. The Countrylines team have an extensive photo reference library, which the models are based on. Generally, the basic form a specific tree, plant or rock is simplified, modelled then textured. Terrain is again based on photo reference and also GoogleMaps, which includes high-resolution imagery of Yanyuwa country. “We use Maya to model pretty much everything - characters, vegetation and terrain. We have been experimenting with Vue Xtream for landscape design, but so far have had trouble finding Australian trees and keeping a consistent look and feel from Maya characters to Vue landscapes,” Brent said. “The mist I add in the very first animation as a way of enhancing the ‘Dreaming’ theme. This look has survived five years and we still use it now. Clouds where originally more abstract but have become a bit more realistic, still digital matte paintings but based on photographic reference from my trips to Borroloola. “The flying fish concept came from ‘The Brolga’ story. In a scene where a flock of Brolga come a cross a rock cod as they fly through the air, they tell it to go back to the sea where it came from. I naturally assumed that as the fish wasn’t swimming it must have been flying, and when this was sent back to Borroloola, the elders loved the idea.” Light and Shadow “Shadows came from the main direction light using ray tracing. To mimic the intensity of the Northern Territory heat, shadows are long and harsh and don’t fade away as quickly. The light angle is set just above zero, but increasing the number of rays smooths this out so it is not too sharp.” The under water lighting is a mix of Maya lighting and post-production. The lighting is similar to the above water scenes, with ambient lights, environment fog and a directional light. Attached to the direction light is an ocean shader, reflecting the light from the water surface onto the ocean floor. For the light rays that shine down from the surface of the water, a separate layer is rendered out from Maya with just the water surface. In After Effects this is then desaturated so it is black and white. The layer is then tilted in 3D away from the camera and a glow filter is added to it on the vertical axis. This gives the impression of the light coming down off the water surface. The layer is duplicated as required and a mask layer can be rendered out should any character swim in front or behind the rays. |

|

|

|

| Travelling Light “Bringing the camera from underwater to above water with this technique is difficult and I haven’t been able to pull it off yet,” said Brent. “Instead, we have just been cutting between underwater to above water. We have been playing around with Realflow and hopefully in future animations we’ll have a nice, clean transition in a single shot. “The first animation I did for the Yanyuwa people was the Songline ‘The Song of the Tiger Shark at Manankurra’. Many of the verses simply describe the landscape, so I had the idea of glowing ribbons of light that would travel the country describing with their dancing what was being sung, like the song being its own character in the animation. John explained this idea to the Yanyuwa elders and we went ahead with it. It was later explained to me that in Yanyuwa, if something is shiny it is powerful. “To produce the ribbons I created a simple arrow shaped mesh. Using a number of joints, I linked them all to the mesh like a spine. I then assigned each joint to the motion path at a different time. So the first joint would go along the path at frame 10, the second at 15, third at 20 and so on. This would start and end with the arrow bunching up, which just meant that I would leave about 100 frames of empty scene before and after the action. Once I was happy with the way the ribbon travelled along the path, I could alter the shape and direction of the curve however I wanted.” Water Dynamics |

|

|

|

|

|

| "I paid a lot of attention out on the Islands with the Yanyuwa people to the way the boats interacted with the water, and also how rough or calm the sea, rivers or streams were. There is also plenty of footage on youTube and Arkive of dolphins and other sea creatures which where great references."

In one story titled ‘The Chicken Hawk and the Crow’, the characters fight over fire. To produce this, Brent attached a semi spherical cylinder to the top of the first stick, attached it to a separate layer so it could be unrenderable, then attached the fire simulation to the cylinder. He said, “Maya’s fire simulation is pretty simple to alter with a few values and it was easy to get a nice fire effect. Lens flares were done in post. A separate black and white layer was rendered out from Maya. A simple black phong shader with a sharp white highlight was attached to anything that was shiny. The rest of the scene was black. In After Effects, I set this layer to screen, so that the white highlight was visible and black was invisible. I then attached a glow filter to the highlight and set it to horizontal only.” Sound Track Recording the dialogue was one of the first tasks completed near the beginning of the production. Brent said, “The dialogue gives the animation its voice. Once it has recorded we have timing to go off and a voice to animate to, whereas ound effects are the last thing on the list. Timing changes so much during the animating and post-production stage that any sound effect linking done early would be useless by the end. www.arts.monash.edu.au |

|