Fernando G Baptista describes the research & techniques behind his beautiful graphics for National Geographic’s feature on Brunelleschi’s Dome in Florence.

Brunelleschi’s Dome |

| National Geographic’s February cover featurereveals the history and design of Brunelleschi’s Dome in Florence through accurate, detailed supporting graphics by Senior Graphics Editor Fernando G Baptista. Here, he describes his research, approach and techniques. |

|

| © Dave Yoder/National Geographic. |

|

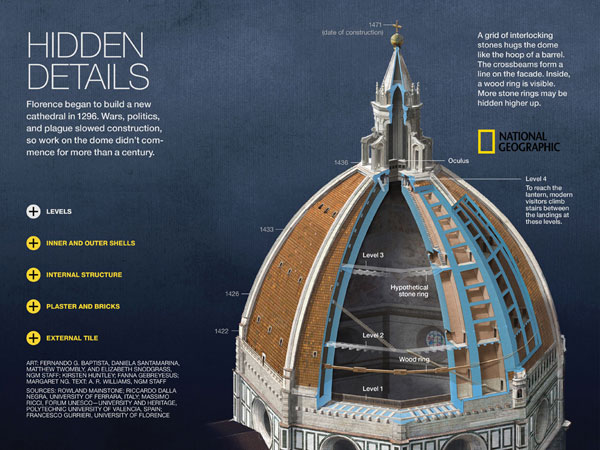

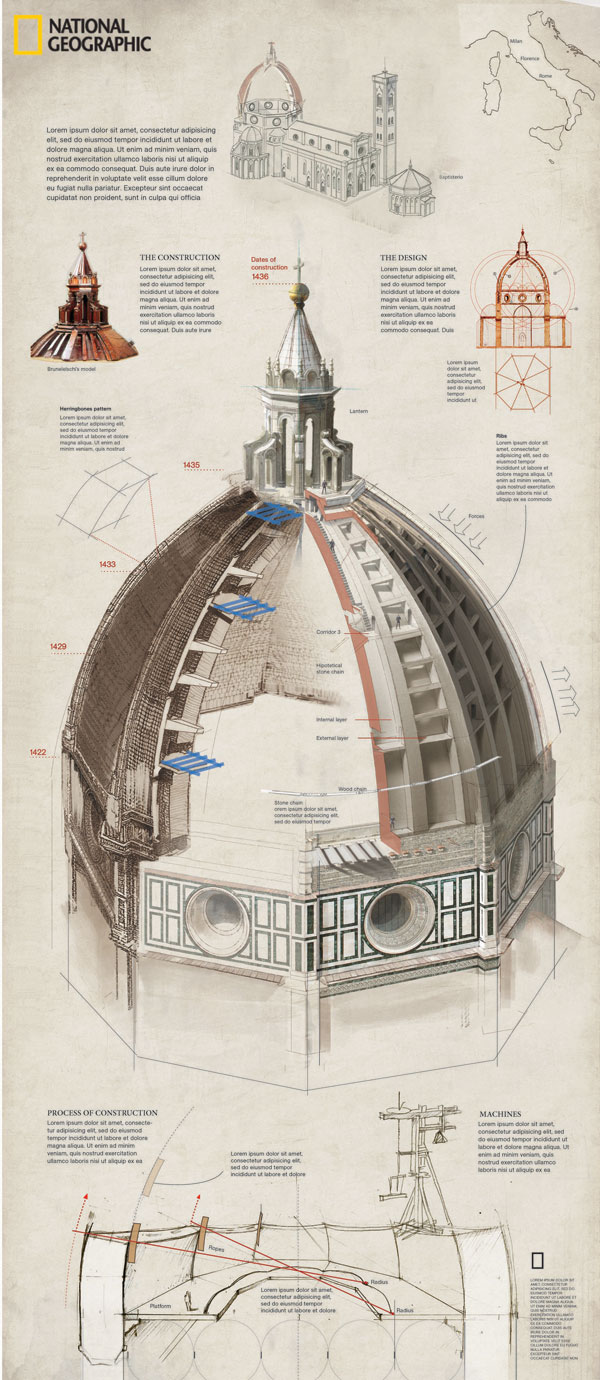

Inaccurate OctagonNo one was able to develop a workable plan for building a dome nearly 150 feet across that would have to rest 180 feet above the ground on top of the existing walls, which were built to form an approximate octagon without a true centre. No one was certain if a dome could be built at all over the octagonal floor without allowing the masonry to collapse inward as it arced toward the apex. Moreover, the architecture prevented the use of traditional Gothic flying buttresses and pointed arches familiar to builders working at that time. |

|

| Art: Fernando G. Baptista, NGM Staff |

|

Filippo Brunelleschi, a goldsmith and clockmaker, became the successful Florentine dome designer, but the engineers, architects and historians of today still do not agree on exactly how he constructed the resulting dome atop Florence's cathedral. Brunelleschi planned to overcome the building’s inaccuracies with a double layered construction comprising an inner and outer shell held together with brick arches and interlocking rings of stone and wood. The rings prevented outward expansion. Further innovation allowed the masonry to support itself during construction - Brunelleschi interlaced the bricks in a herringbone pattern as he built the domes from bottom to the top. |

|

| Photo by Mark Thiessen/National Geographic |

|

|

| © Dave Yoder/National Geographic. |

|

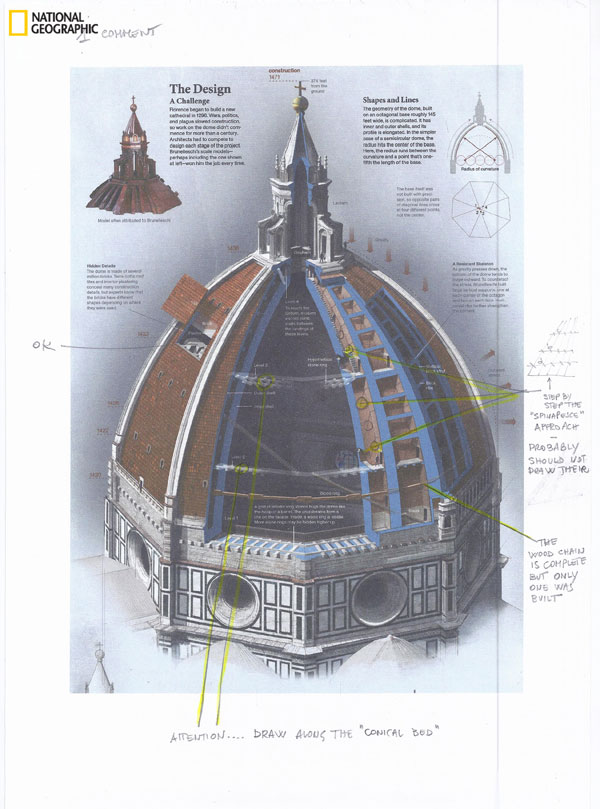

Florentine Specialists“I did a great deal of research in the few days before I headed to Florence, preparing questions, diagrams and drawings about Il Duomo - Santa Maria del Fiore’s dome - to be confirmed by the experts. I spent five days in Florence where I met with three specialist architects, some of whom have spent their whole careers studying Brunelleschi's dome, who sketched for me their understanding of all the details of constructing and designing the dome.” |

|

| Art: Fernando G. Baptista, NGM Staff |

|

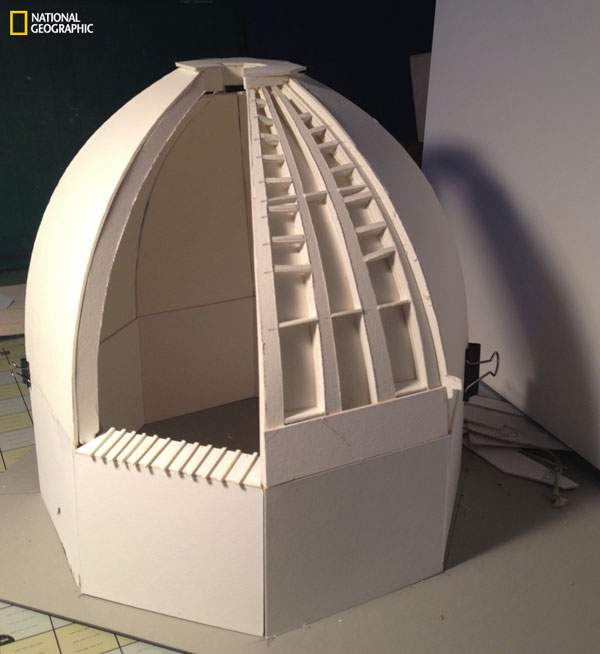

Fernando visited Il Duomo museum where the models attributed to Brunelleschi and the tools used in the construction are kept. A special part of the research was seeing a 1/5 scale model that one of the specialists was building in a park in Florence. Seeing this model helped him to better understand and visualise the structure of the double shell of the dome. “Of course I visited the dome itself,” he said. “Over the course of the week, I went four separate times and spent hours going up and down within the walls of the double shell and getting into restricted areas—a neat perk of doing this research. |

|

|

To make the animation, hundreds of frames were drawn. This segment, which shows Il Duomo architect Brunelleschi walking, featured more than 100 frames. Art: Fernando G. Baptista, NGM Staff |

Back to the Drawing Board“I took around 500 images of the dome and of the scale model and finally, with all of this material, I returned to Washington DC. The curious thing was that the more I learned about the dome design, the more questions I had. Instead of sophisticated engineering techniques like LIDAR scans, photogrammetry or survey, this project was carried out using observation and abundant, careful research. “We had ongoing back-and-forth communications with our specialists, who helped us to verify every detail to ensure the elements were as accurate as possible. I also relied on their own resources - for example, architect Riccardo Dalla Negra has compiled plans, complete with diagrams and measurements and cutaways that proved invaluable. “ Fernando’s two resrearchers, Fanna Gebreyesus and Elizabeth Snowgrass, were critical to his work, particularly for an in-depth project like this one. They are responsible for getting information, checking that it is correct, and serving as an ongoing link with the experts. “The two researchers worked tirelessly on this project. They communicated with more than 15 experts and probably exchanged hundreds of emails to be sure we got every detail just right,” Fernando said. |

|

| © Dave Yoder/National Geographic. |

|

“The writer, Tom Mueller, shares a fascinating narrative that offers a background of the times, of Florence, and of the many facets of Brunelleschi, a fascinating character and a technical genius. Dave Yoder’s photographs provide a modern context of this incredible structure. And the graphics themselves, which look into the construction of the dome itself, were a group effort, right down to the carefully crafted captions.” 600 LayersFernando works with a mixture of traditional tools and a computer, always starting with a pencil sketch, although sometimes his early sketches are fairly abstract. Then the main idea is embodied in a computer sketch, which he makes using Adobe Illustrator. |

|

| LEFT: A model built for reference for the artwork, in the process of construction. RIGHT: Sculptures made for the design of the character featured in the video animation. The sculpture on the right was the one that was selected.Art: Fernando G.Baptista, NGM Staff |

|

“Then I add colour and details to the picture and refine it with several layers of texture using Photoshop. I make the texture layers with watercolour or by scanning and overlaying different materials, such as paper. I also use Illustrator to add the technical lines and secondary diagrams. For the Il Duomo illustration I created more than 600 layers in Photoshop which I merged and made into a single graphic.” |

|

| Art: Fernando G. Baptista, NGM Staff |

|

You can also see the animated graphicshere. |

| Words: Adriene Hurst Images:ART - FERNANDO G. BAPTISTA, DANIELA SANTAMARINA, MATTHEW TWOMBLY, AND ELIZABETH SNODGRASS, NGM STAFF; KIRSTEN HUNTLEY; FANNA GEBREYESUS; MARGARET NG. TEXT: A. R. WILLIAMS, NGM STAFF. SOURCES - ROWLAND MAINSTONE; RICCARDO DALLA NEGRA, UNIVERSITY OF FERRARA, ITALY; MASSIMO RICCI, FORUM UNESCO—UNIVERSITY AND HERITAGE, POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY OF VALENCIA, SPAIN; FRANCESCO GURRIERI, UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE |