Framestore visualised the dramatic internet activity behind WikiLeaks, creating rendered effects and motion graphics for Alex Gibney’s documentary.

STEALING SECRETS |

|

Alex Gibney’s documentary feature ‘We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks’ employs motion graphics created at Framestore to visualise events that occurred through the internet. Framestore’s design team in New York created over 35 minutes of rendered effects for the film, shown at Sundance film festival in January 2013. Networks and ParticlesThe team’s initial conversations with director Alex Gibney focused on two key features of the story. One was the chat logs between Private Bradley Manning and computer hacker Adrian Lamo, and the other was a visual representation of the world wide web plus the articles, tweets and products that help tell the story. As they looked for reference, the team found plenty of artistic interpretations of the internet, most of them inappropriate and fairly “cheesy”. To combat this they tightened the brief, and aimed to give each shot a sense of growth. The tone of this film is often sinister, similar to the ever-growing web, and so the documentary seeks to piece together a multitude of facts and elements to create a whole picture of the events. |

|

|

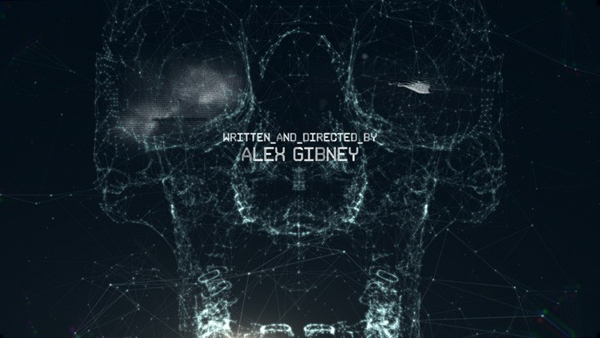

Framestore’s Senior Design Director in New York Marc Smith said, “We started to draw reference on the spread of information from satellite imagery of the earth and electrically illuminated city networks, molecular growth of cells and viruses, flight path patterns and the microscopic magnetic banding on hard-drives as data is added. Many of the discoveries came from our animation tests using various 2D and 3D particle generators.” Alex Gibney and the team were especially drawn to tests created in Trapcode Form2, Particular2 and Cinema 4D’s Thinking Particles. Layered TitlesFramestore was also approached to create the main title sequence, which Marc led. From the first concept presentations, the director and the team favoured concepts created using particle systems within After Effects and Cinema 4D. They were looking for a technique they could use to break apart and draw together the footage and images over time, within a 3D space. The elements were sometimes abstract or only legible from certain angles of view, but this concept, along with the design and animation of the main title sequence, was the starting point for several sequences. The main titles sequence, in particular, employed a combination of software and techniques. “For the particle builds, I was interested in combining the features of the Trapcode Suite, Form2 and Particular2, with the recently developed Rowbyte Plexus2 software and C4D,” Marc said. “This gave us a great degree of flexibility and control in animation. Starting by building models of Assange and Manning’s heads within C4D, these were exported to both Form2 and Plexus2, and used to drive their generators. Over the course of the main titles, these multi-layered heads begin to build, shift and reveal themselves slowly by attracting to each other and forming interconnected web-like clusters. |

|

|

“Along the way, we see a prologue of imagery relating to the film’s content, also forming out of the darkness. Lastly the typographics themselves were created and refined in Adobe Illustrator, exported to C4D, then exported back to Plexus2 and Form2 in AE. At last count, the project for the main titles contained just over 400 layers, controlled with random generators, scripts and even keyframing the effects manually. We chose techniques on a shot-by-shot basis.” Once a look for the titles had been established with a series of approved styleframes, the team cut draft animatics in After Effects CS6 to refine and sign-off timing, before beginning production in Cinema 4D and After Effects. The main advantage of using Cinema 4D is the way it natively interacts with After Effects, their final compositing tool. Cameras, lights and model information can be readily passed back and forth between the platforms, providing a smooth workflow for the artists. Sinister EdgeThe look achieved was a good match for the narrative of the film as well, by compiling a wide array of elements and evidence. Marc explained, “The creative also focused on the need for a sinister edge in keeping with the film’s content. The colour palette was kept dark and minimal throughout, and the camera work might suddenly lurch or dive. What appeared to be random set of pixels at first would organically shift, twitch and grow to reveal an interconnected whole.” |

|

|

Designing the chat logs for the film began as a collaboration between the project’s Creative Director, Murray Butler, and Framestore’s Head of Design in New York, Maryanne Butler. “The chats needed to feel textural and alive, sinister and at certain times, lonely. So much of what the logs expressed was a personal outpouring from Private Manning so we had to stay sensitive to the subject in visualising these,” said Maryanne. “We wanted the chats to have a life to them so we experimented with shooting simple white on black animated type off of a plasma screen using both a 5D and 7D camera, adjusting shutter speeds on both to find the right level of pulsing and glow that occurred around the text,” Mayanne said. “The results differed from camera to camera so we used the best textures gathered on both to composite the results. Our favourite screen texture was then looped and graded so it could be used when the text animated over actual picture backgrounds, so that they too, could live in Manning’s screen world. A batch set-up in Flame incorporating some Sapphire 6 sparks was used to mimic the shot footage in these instances.” Loneliness and DesperationWhile exploring the chats they wanted to them to be textural, but more analog than crisp and digital. Shooting TV screen imagery was always part of the plan, which they never strayed from. “In the beginning our textures were quite heavy handed and moody. A lot of the original idea was to give Manning’s chats a military feel, so we used greens and beiges. I wanted them to feel like they were being transmitted on a bad line from Baghdad, but it started to distract from the chats themselves, and they were too important to the film so we simplified them pretty quickly,” said Maryanne. |

|

|

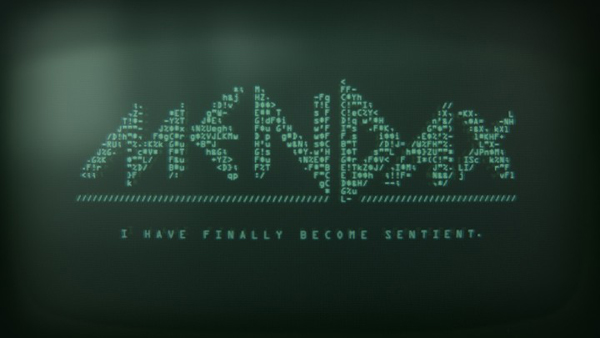

Graphically, they played with mirroring the chats between Manning and Lamo, having them both on screen at the same time and moving in different directions, but each individual line was so expressive that they chose to leave them isolated to help clarify the story and emotion. Another idea was to isolate certain words from Manning’s chats and let them linger like ghosts, but they decided that the lines were powerful enough. She commented, “I always wanted to keep the text a very simple font, Arial in this case, so you didn’t pay it any mind, and it worked well. Having Manning’s chats remain in their dark, textural void really helped express his loneliness and desperation to share what he was going through and what he had done. In contrast, we flipped the switch on hacker Adrian Lamo’s lines so that they were the negative versions, in black and sinister type looking over a brighter background. This instantly showed how controlling and manipulative Lamo was compared to Manning’s vulnerable state.” Noble LiarMendax, ‘noble liar’, was Assange’s hacker name in the late 1980s. When designing the name for this segment of the documentary they needed to keep the ‘80s aesthetic. However, simply typing ‘Mendax’ didn’t seem to do Assange’s brazen hacker personality justice, so they gave it a bigger look, similar to rock bands of that era. Maryanne said, “Knowing computers of the time couldn’t generate large fonts, we used ASCII art to create the final Mendax image. The same technique was used in the actual 1989 ‘Wank Worm’ message which inspired the design. The Wank Worm was a computer worm that attacked DEC VMS computers at the time. It is believed that Assange and his group were behind these cyber attacks.” |

|

|

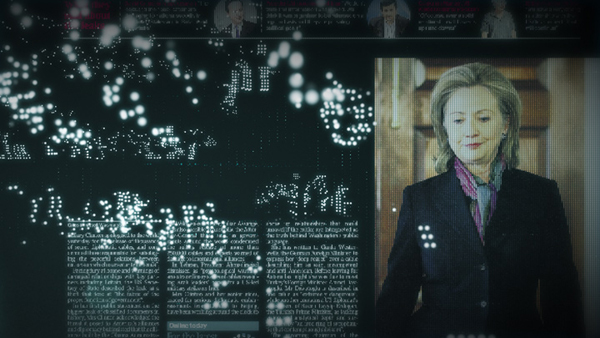

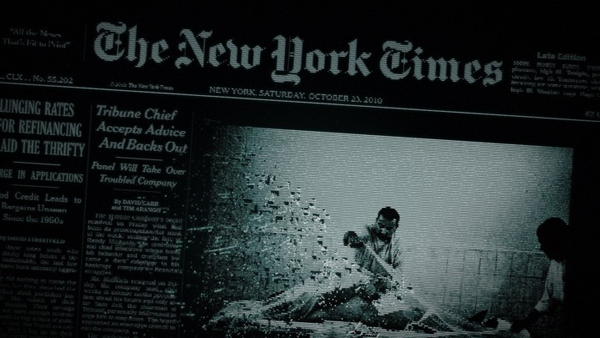

To visualise the data streams being exfiltrated, artist Zack Lydon created more concepts, which were then animated by artist Gabriel Pulecio using a combination of After Effects and C4D. The huge quantity of publicly revealed war logs were designed and animated by concept artist Callum Mckeveny. One image resembles a wide abstract landscape composed of small dots and lens flares. This still is from a big data exfiltration sequence – a graphical representation of data streams being released from Private Manning’s computer to WikiLeaks. Maryanne said, “In this sequence Manning brags about listening and lip-synching to Lady Gaga’s telephone “while exfiltrating possibly the largest data spillage in American history”. The entry into this door of our cyber world uses the sound waves of the Gaga track which soon turns over into wave that continues as a mass of thousands of files, illustrating the sheer volume of classified data being released. Gabriel used a combination of both C4D and After Effects to create this beautiful digital landscape. We believe it’s one of the most breath-taking sequences in the film.” Making HeadlinesAnother major element of the project was recreating the many headlines that followed the WikiLeaks story and news about its founder, Julian Assange. Alex Gibney wanted these articles to be part of the ‘web-world’ as well. The majority of the content was supplied directly by the client, often in examples that Framestore’s artists needed to re-create at the required resolutions before treating. As a documentary, the integrity of the imagery being shown is paramount, and care was taken to keep any recreations authentic to the originals. |

|

|

“Conversations with the director often centred on how these images were framed or revealed to best serve the story being told. Early on in the process, we knew that the resolution of source footage might be an issue at times, so the solution to recreate these with particle systems – playing with pixelation, compression damage and artefacts – worked in our favour,” Marc said. Red Giant’s Trapcode Form2, with Particular2 and Rowbyte Plexus2, were again used for most of the particles work. The ability to keep everything within the After Effects timeline served them well due to the fast turnaround required and the flexibility it provides for editing. Although a number of C4D particle systems were also employed, these tended to be slower to produce. Once a template had been created for the headlines for example, many of the final shots were completed in less than a day. Twitter Drama“Starting with a base image or length of footage, we would then use this to generate luminance values within After Effects to drive a Trapcode Form2 image,” Marc explained. “The size, number and various behaviours of these particles were all controlled through the plugin, and by manipulating the brightness and colour values of its source. In addition, we then created mattes with random noise generators to combine with Particlar2 to provide a more organic feel to the forming images.” |

|

|

Camera animation was also created in After Effects and, after finalising, was run through a process of final colour corrections and lens effects. Using ‘real world’ lens treatments - such as added depth of field and chromatic abberation - gave the shots a less rigid animated feel, and also aided us in controlling any unwanted moiré or scan-line distortion. Additional effects created for the project ranged from compositing crash-zooms, to Twitter dramatisations, video effects and creative graphic representations of important documents, which were realised with After Effects, Flame and Cinema 4D. The Twitter dramatizations were graphical renderings of some tweets WikiLeaks had posted. They needed to work with the web articles, and were treated with more presence on the screen than an actual Twitter band. All articles and tweets that were posted over the internet were treated to show that they existed in a web world, and to provoke the feeling that what we were seeing was live within the documentary’s storyline. www.framestore.com |

| Words: Adriene Hurst Images: Courtesy of Universal Pictures and Framestore |