|

John, not a proponent of the liberal use of effects in movies – even a movie like this one depicting planet earth as it rapidly slides into dark, cold oblivion - had seriously

underestimated the need for visual effects in ‘The Road’. Fortunately, by engaging the team at Dive, he found himself working with Mark Forker, who has long experience in

realistic, invisible effects and photographic work. Their first estimate swelled from under 75 to a maximum of 125 shots, but the end count came to just under 240.

In Katrina’s Wake

Mark took on the roles of Visual Effects Supervisor and digital plate photographer. He and his crew started shooting material for their work in February 2008, continuing intermittently until July. By far the majority was done within the state of Pennsylvania, where Dive is based in Philadelphia,

but they also needed to capture some plates and elements around Mount St Helens in the state of Washington and in New Orleans. The shoot occurred in the period after Katrina had blown through, providing debris and views of trashed suburbia that was a good match for ‘The Road’.

They spent the first ten weeks of post with the director’s cut, working out unexpected tasks that emerged and finding extra staff. Dive is a relatively small company and as the scope of work on ‘The Road’ grew, Mark sought friends in Los Angeles, from his days working at Digital Domain, in New York and Toronto, to work as 3D CG artists, matte painters and compositors.

“When John began on the project, he approached VFX at arm’s length,” said Mark. “He told me, ‘We’re only going to use it when we have to. The least we have to interfere with any frame, the better.’ Actually, I agreed. I really don’t tend to push a production toward effects. I come from a photographic background, and like getting involved with this side of filmmaking. The shoot is my first approach to ensuring that our work conforms to the photography and original vision of the film.”

New DI Suite

One way Mark overcame John’s reticence was by using the new DI facility Dive had just finished, with a 2K projector and in house colourist. Although John had arranged for the final DI and sound to be completed in LA, while he was in Philadelphia working on post very early in the process, Mark took him into the theatre with some of their critical scenes and listened to him describe in detail exactly the way he wanted the film to look, from beginning to end. The team then applied precisely these same colour corrections to the scenes, to show him how they would look in

the finished film. In other words, while they were actually working on the shots in a fairly neutral colour space, they could present them to him for review in the final DI colour

space. Mark believes this added service was an important reason John gained confidence in the potential advantages of altering certain shots, without losing his vision. It also improved the quality of their work.

Filming locations

The diverse filming locations had been researched by Production Designer Chris Kennedy, working with a location scout. The main location was Pennsylvania, which had the right sort of water features, wide open landscapes and, taking the lead role of the road itself, the old portion of the Pennsylvania Turnpike. This highway, disused for over 60 years and looking decrepit and neglected with no businesses built on it, provided some key locations. Mark did second unit photography for many of his plates, including a number of stills with a Canon 5D, sometimes in a

different location but always sticking closely to the look of the main shoot. When he was in New Orleans shooting elements, for example, he needed to spend an extra day or so gathering

images of signage, textures and other evidence of wreckage still remaining in Katrina’s wake. Because the scouting had been done some time before shooting, much of the scenery

they wanted had already been cleared up, which later precipitated into some extra FX work as well, to replace the devastation. “Good for the city, bad for the film,” Mark joked.

Thieves and Earthquakes

One of the major effects sequences in the film showed an earthquake that shook the woods where the main characters, the father and his son, were hiding. Some green screen work was required when trees toppled over onto the actors, dust and debris were added and snow was thrown up as the trees hit the ground. Almost all of the 25 shots had camera shake added, and atmospheric effects were added to make it all work.

A very subtle sequence with many effects shots occurred when a thief robbed the man and his boy, and they ran to apprehend him. The thief was a man who had lost his thumbs while trying to survive in the harsh new environment, and originally the director had planned to shoot the scene so that only a handful of shots would need any treatment. But in the end, it actually became a dramatic, prolonged sequence in the story and demanded some very careful, invisible work done to about 30 shots to invisibly remove his thumbs. An important group of effects shots included the big, wide open shots that show the man and boy on their hopeless journey, appearing in the foreground or just barely passing through at the edge, and serve as establishing views to make viewers understand the harsh conditions the characters were facing. Almost all of these required some kind of work. Many of them contained large features such as bridges, and railway poles and

trestles needing damage applied, including heavy weathering and storm damage combined with neglect.

Shopping Mall

Mark put the elements he had managed to capture in New Orleans to good use when he needed to create shots of an abandoned shopping mall. The location scout had identified a suitable wrecked mall but on their return months later, they found that the site had been cleared, bar one last building. So they shot that, and digitally replicated it into the background of the plate. They added damage and a car park full of debris, by compositing and projecting photography onto bits of 3D CG architecture. The stretch of Turnpike that they were using actually contains no billboards. All of these were built from 3D architecture with projected photography. Some other minor 3D CG elements were extra snow and dust, flying through the earthquake sequence for example, and CG ‘breath’ in the air when characters talk in cold places.

No Flowers Please

General ‘atmospheric, reparative shots’ also formed a large category of shots Dive handled. They removed green trees and other vegetation, no small task considering that Pennsylvania and the American northwest are naturally very green regions, even in winter, when the film was shot. They

also replaced blue skies with brooding cloudscapes and, following John’s insistence that “no green, blue or flowers” were allowed to remain, all evidence of insects, birds and living things were removed. “One bug was allowed,” said Mark, “a cockroach that emerges from a tin can.”

Although a practical FX team was at work at every location adding real snow and dust, this sometimes needed enhancement to cover the breadth of the shot. They would treat only the foreground and Dive made extensions of this look over the rest of the scene. They worked with three weather scenarios during the shoot – a couple of actual snowy days at the start, the practical added snow and CG or replicated snow. All three had to blend naturally.

The director was closely consulting with ‘The Road’ author Cormac McCarthy, and had read some of McCarthy’s early manuscripts. He intended to follow the book as closely as

possible while maintaining cinematic quality. At first, he tried to shoot everything in the book, to accommodate expectations of the book’s many fans, but the footage grew to four hours

long. He aimed instead to keep enough to preserve the story.

A Photographer’s Eye

Forker’s background is quite varied. He started working in

the commercial world. When he moved into film, one of his first features, ‘Apollo 13’, had a brief to keep the effects as invisible as possible. When some of the astronauts saw it, they

thought they were seeing actual live footage from the mission that they had never seen before. Subsequently, building on his photographer’s training, his preference has always been for

re-creating reality through VFX, emphasising photorealism, and not depicting a fantasy world.

Nevertheless, when fantasy projects such as ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’, ‘Peter Pan’ and ‘Star Trek’ came his way, he always accepted and put just as much effort into

them. Instead of generating explosions or using animation, he favours compositing, matte paintings and photo solutions to problems. “There are always two or three ways to approach

FX problems. CG is common now and certainly valid but I tend to lean on photography, and shoot as many elements as possible.” He has taken the role of compositing supervisor on several projects. To create those essential, expansive industrial landscapes the story inhabits, he sometimes compiled images he had shot, found others online, and some were giant matte

paintings comprising a lot of distant cityscapes and buildings. He also keeps a library of cityscape and landscape shots to use in various projects.

Many Hands

When Mark refers to his team, he’s in fact including artists from several other vendors. Crazy Horse, for instance, produced a number of these matte paintings. Mark provided some of the elements to fit into spaces but they supplied or created some of their own. Work was not strictly ‘farmed out’. Mark created a single team, some members of which didn’t

happen to share the same office. Christa Tazzeo from Invisible Pictures did most of the earthquake shots. Artists from Eden FX, Space Monkey and Brainstorm Digital also contributed. He wasn’t always aware of which company’s work he was looking at any one time, but held a couple of daily progress meetings via CineSync. “As long as the groups are provided with exactly the same clip on your own local network,” Mark explained, “CinesSync lets you play it simultaneously, mark it up together and talk it over. The project overall ended up 50/50 between Dive and the other vendors, that is, Dive completed 120 shots and the others finished 120 as a group.”

Toolbox

The other vendors adopted essentially the same pipeline. Nuke was used for almost all compositing. Sometimes they would begin with After Effects or Shake, for a specific tool, and then pass to Nuke. Maya, Lightwave and modo were their 3D tools, and Syntheyes and Imagineer Mocha for tracking. 2D artists were relying on Photoshop for textures and mattepainting, and Silhouette and Nuke for paint and rotoscoping. Dive ran a Qube! render farm.

Shipwreck

The coastline, an important feature in the story, was shot mainly along the Oregon coast except for some captured a Lake Eerie in Pennsylvania. “The Oregon coast is frequently overcast, useful for this story. The Great Lakes often give the impression of ocean coast, although Eerie’s numerous jetties had to be removed. Much of our work was to create uniformity across the different shorelines and environments. The different weather conditions were normalised by making the bright sunny days match the foggiest shots.” “A scene involving a wrecked ship required photography to be projected onto some 3D geometry. The camera was kept still enough to give the impression of a real object. They used some photos of a few different ships blended together and manipulated into a patchwork ship.”

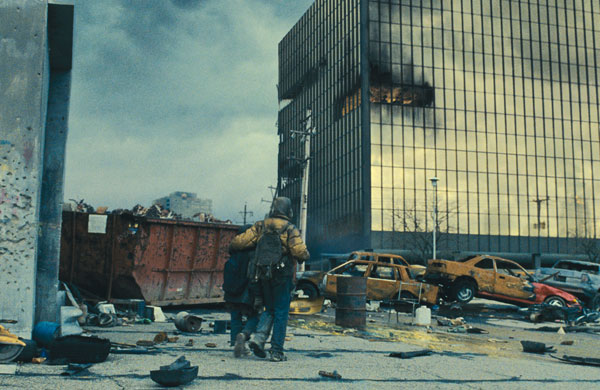

Suburban Devastation

A dramatic sequence takes place among a group of suburban family homes that the two characters come across. They used a town in New Orleans that had been under construction when Katrina hit. Much of what the audience sees was shot in camera – the site as it was found, dressed with old cars and other props. But in the end, it required a lot of additional work in post. A wide shot showing the father and son walking down the central street only had the right side of the neighbourhood intact. The left side had a freeway running through it, which

meant Dive had to reconstruct neighbourhood elements on the left to complete the scene.

Back to the Beginning

Towards the end of production when the film was virtually complete and they were satisfied with their effects work on such scenes, the director told them, “We don’t have enough

skeletal remains yet through the whole film. Think of how many people would have been dying.” Always ready with his camera, Mark collected bones, sSaveome old clothes and shoes, shot them on Dive’s stage against green screen, keeping in mind where they were to be used, and comped them in. The fixes didn’t turn out to be too difficult. “It was in some ways a return to the solid, basic VFX work I had applied to Apollo 13. The director started out trying to avoid VFX but now looks forward to working with us again, using effects in new ways. I feel as though my mission has been accomplished,” said Mark. “John began by telling us, ‘There are only three main characters in this film – the man, the boy and the environment. The last might need a lot of work.’ But I expect most viewers will watch unaware of what we have done.”

|