In their new book, filmmakers Ben Allan and Clara Chong talk about navigating the new Apple Immersive Video format, sharing tips, discoveries and storytelling experiences.

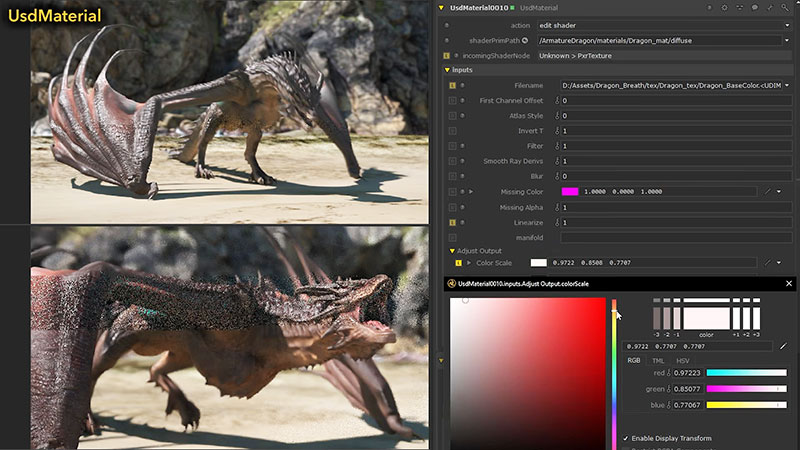

As you look at the images in this article, consider – where would you, as the storyteller, invite the viewer to step in? How would you encourage your audience to focus on the right elements?

Filmmaking has traditionally been a way to visualise stories. In their new book Cinematic Immersive for Professionals, Ben Allan ACS CSI and Clara Chong open the world of immersive video to storytellers, a technique that moves beyond framing shots, to creating experiences. They describe the art and process of immersive cinema as a new visual language that speaks not just to the eyes but also to the mind, body and memory of the viewer.

Ben and Clara, founders of Main Course Films in Sydney, each have over 30 years of professional experience in video production, having written, directed, shot, edited, graded and post produced numerous projects from documentaries to dramas. More than that, their pioneering effort in metadata integration, colour fidelity, workflow optimisation and new formats has given them an edge as they approached immersive video production.

Talking the Talk

Because the creative possibilities of this new language are so vast, it can leave the storyteller wondering where to begin. Fortunately, like other mediums, it has limitations and makes demands that inspire and challenge us creatively. In their book, Clara and Ben identify those limitations and show how they have learned to take advantage of the medium’s rapidly developing technology – the Apple Vision Immersive (AIV) format and the Blackmagic Design URSA Cine Immersive camera – to build their own experiential stories.

As they step into this very new storytelling medium, readers will find the authors’ experiences and discoveries extremely valuable. They will find practical, hands-on style advice and tips to take on set – as well as encouragement and inspiration. Equally important, immersive production is a fascinating topic in its own right – an art, a philosophy and a science rolled into one. The authors successfully communicate their excitement about its implications for modern cinema and stories everywhere.

Watching AIV material might remind you of breaking the 4th wall – but in reverse. Instead of seeing a character peering through the aperture to address you directly, you’ll find yourself pushing into the world of the story, into its spaces, light and ambiance.

Using Ben and Clara’s concept of AIV as a new story language, readers will see how every movement is a word, every pause a punctuation mark and every shift in perspective a chance to connect with the viewer’s sense of presence in the world.

Letting Go of the Camera

If you are a filmmaker or cinematographer already, the importance of how viewers feel, move and experience a story physically from their perspective inside the world may come as a surprise. The authors stress that physical comfort is important – when content is captured and edited with viewers’ wellbeing in mind, the medium itself should disappear, allowing them to connect directly with the scene around them.

Because immersive experiences are so closely linked to physiology, storytelling needs to reflect not only how people watch video but also they remember stories. How do our brains construct real experiences – integrating space, sound, emotion and meaning within the world?

While traditionally, cinematographers are concerned with fitting elements inside a frame, AIV is concerned with how close together they are, the action around them, and where the viewer is looking. These physical forces are what help you express emotion and guide your decisions, from blocking to sound design. Your goal is to guide perception, rather than control it.

Clara and Ben discovered that letting viewers look where they choose throughout the experience changed their role as storytellers. As the focus moves from what the camera captures to what the viewer perceives, it’s necessary to direct both the subject’s movement and the viewer’s perception.

Framed vs Frameless Filmmaking

Making the leap from framed to frameless filmmaking may seem daunting at first. How can you define the geography of the story without a frame? How will viewers find your characters and follow what they are doing without camera work to lead them around? This book not only gives you the building blocks of a production – the AIV format to define the media, Apple Vision Pro as the viewing device, and the visionOS operating system as the interactive environment that makes the experience possible. It also shows you a way to create the anchor points for viewers’ orientation.

The 180° field of view (FOV) is a key element of AIV that makes an experience immersive, by surrounding the viewer with the scene captured from the real world. Although, at any given moment, the viewer actually sees less than a quarter of the full image, Clara and Ben explain how this anomaly becomes a creative advantage. By anticipating that viewers may overlook details unless their gaze can be gently guided, directors gain the space to tell their stories more clearly and with more impact.

Consequently, the viewer’s gaze is another key concept in AIV. As storytelling shifts towards spatial design, movement and presence, it’s less about showing and excluding, and more about inviting people into a world that surrounds them. It gives you three dimensions where viewer comfort, cognitive load, attention and gaze behaviour are not stylistic choices but essential creative foundations.

Gaze now takes on many of the roles once managed by the camera operator, making a physical shift in how stories are experienced. The filmmaker anticipates and guides viewers’ gaze so that the essential story beats are still there.

Physiological Reality

Inside the Apple Vision Pro, AIV places the viewer in an identifiable 3D scene. Spatial context and proximity are your tools for guiding attention and supporting storytelling. From this foundation, filmmakers still have a wide scope for creativity.

Within the creative grammar concept are even more tools. Blocking and viewer comfort zones, composition and movement relative to the viewer’s position, using sound for orientation and earning viewer attention, not assigning it.

Blocking is about how people, props and camera are positioned in 3D space relative to the viewer’s position. It directly affects comfort and coverage and therefore needs to not only create space for the camera but also the viewer within the scene. Because the viewer is inside the world captured by the

filmmaker, and can accurately perceive scale and distance, proximity becomes your tool that shapes emotion, comfort, intensity and understanding of character.

Immersive realism depends on spatial credibility – in other words, when lighting, object scale, stereo convergence and sound placement align, the brain treats the scene as real. Furthermore, as mentioned above, human memory doesn’t record events as a camera does – it reconstructs them, which also helps to build your story.

Where Am I?

Understanding the camera as the viewer's body, not just a lens, with its own height, orientation and motion is a key concept. It integrates body position into our interpretation of space and narrative, and helps tremendously to bring the experience of the linear story to life. Immersive storytellers will learn to choreograph their viewer’s attention, minute by minute, through biological timing.

For instance, in immersive space, viewers should be able to orient themselves naturally, track relationships between elements and build meaning from beginning to end. If scenes are too dense, depth changes too frequent or the environment is spatially inconsistent, your audience soon grows tired and disorientated, or simply disengages. Clara and Ben explain how to manage those situations by structuring spatial hierarchy, pacing the motion and using proximity – in short, avoiding overstimulation. (Unfortunately, that means camera panning is out!)

Human comfort thresholds serve the director as biological stop signs. Familiar factors like frame rate, stereo depth and audio placement can be tuned to avoid overload. In fact, in AIV workflows, these thresholds are not theoretical – they are important enough to be built into the system parameters – frame rate at 90 fps,

stereo convergence, and locating sound in space.

Creating the immersive experience for your story is not separate from its narrative design – it’s the framework in which the story lives.

Locating Sound

Audio tracks have never been more important for storytelling than in the Immersive format. By nature, viewers are acutely aware of where sounds should originate to match what they see. The visuals may tell you where you are, but the sound tells you where to look – and how to feel. The Apple Spatial Audio (ASA) places the viewer sonically inside the world. More than a supporting layer, audio here is navigational, lending emotional and perceptual structure to an experience.

Therefore, the recommendation is to record effects and dialogue as mono tracks, and then precisely place them in 3D space during the mix using ASA object metadata. Sounds are then rendered adaptively during playback, taking into account variable acoustics like room geometry, object and listener location and orientation.

Getting Practical

Hopefully discovering how AIV works to bring storytellers closer to their audiences has inspired you and filled your head with ideas for stories that will come to life inside the Apple Vision Pro. Fortunately, Clara and Ben do not leave us hanging at this point – in this book, practical considerations begin where creative vision meets production reality.

One of the most valuable sections is a hands-on guide to using the Blackmagic Design URSA Cine Immersive Camera. With the creative framework for AIV firmly in hand, this section translates those ideas into on-set practice – camera placement, equipment choices, spatial audio capture, monitoring options and dailies.

Readers now learn about the BRAW Immersive codec, which packages synchronised stereoscopic images together with projection-mapping metadata. It’s reassuring to know, for instance, that BRAW makes it possible to record stereoscopic 3D as a single file. Left/right synchronisation is handled in-camera, so that files move through the pipeline much like 2D media.

Because each camera is factory-calibrated, the relationship between the sensor, the lens and real-world space is also encoded into the metadata of every BRAW file. During playback – even when intercutting between cameras – the visionOS uses that metadata to reconstruct geometry

Setting up a professional cinema camera can be arduous, and for stereoscopic rigs, the process is often even more complex. URSA Cine Immersive simplifies this dramatically. Moreover, the URSA's integrated lenses mean there's no need to change or mount lenses. A matte box or external filter system literally cannot be used and, due to the camera's deep focus and fixed aperture, a follow focus, iris motors or remote focus systems are not required.

Accurate Measurements

Accurate measurement is as important for AIV production as it is for conventional filmmaking. However, every pixel in an AIV image corresponds directly to real-world space, so what matters is not the pixel dimensions of each frame, but pixel density and how it maps the captured world onto the viewer’s perceptual field in 1:1 mapping. This calls for a set of critical measurements that Clara and Ben clearly explain and define.

Clara Chong and Ben Allan ACS CSI

For example, the ratio of pixels per degree (PPD) describes how many pixels fill each degree of the viewer’s FOV. It expresses clarity in the same terms as viewers’ eyes as they take in a real scene. It also allows us to quantify sharpness very precisely: Resolution (pixels) ÷ FOV (degrees) = PPD

Framed formats don’t have a fixed PPD because pixel density depends on the viewer’s distance and position relative to the screen. But in AIV, 1:1 world mapping means every viewer experiences the same PPD, every time. In fact, its consistency is one of the foundations of its perceptual realism, making sense of wherever the viewer looks.

Meanwhile, the MTF (Modulation Transfer Function) measures how well an imaging system transfers contrast from object to image at a particular resolution, strongly influencing how well we perceive sharpness, and pixels per second records how much visual information the viewer receives each second. All together, the relationship between field of view, PPD, MTF and pixels per second forms the perceptual backbone of the AIV experience. www.maincoursefilms.com

Review by Adriene Hurst, Editor Digital Media World