David Scott at BlueBolt talks about building period environments, awesome lighting and invisible but terrifying effects for Director Robert Eggers production of Nosferatu.

Nosferatu, one of the oldest and most terrifying of all horror stories, has come to life on screen once again thanks to director Robert Eggers. Working alongside him was the team of visual effects artists at BlueBolt in London, led by VFX Supervisor David Scott.

Robert Eggers had first written the script and produced a stage version of his Nosferatu when he was only 17, inspired by the silent 1922 film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror and by Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula from 1897. Bringing the film to the cinema screen has been a fascinating task, both for the production and for the post production teams, and it has earned recognition from critics and nominations for Awards including the VES, BAFTA and Academy Awards

Digital Media World had a chance to talk to David Scott about BlueBolt’s work on this film, encompassing over 250 shots. “We knew from working with Robert on The Northman that he wants to avoid letting his movies feel like VFX films in any way. He aims to capture as much in camera as possible, using VFX only for when that’s impossible while keeping the effects totally invisible,” David said.

“We had built our earlier relationship with him on that understanding. We were keen to go ahead with Nosferatu – nevertheless, the prospect was daunting because we knew his preference for extremely long shots that would put our work to the test. Those lengthy shots expose our CG assets and compositing to audience scrutiny and leave us nowhere to hide.”

Production VFX Supervisor Angela Barson was handling onset supervision in the Czech Republic, where most of the principle photography took place, starting in early 2023. Sequences were mainly recorded in studios in Prague, and some at a 14th century castle and other locations near Prague. Angela and David kept in constant dialogue about how the production was proceeding. If an issue came up, she would call or send images and they would discuss various approaches while she was still on set with the director and DP.

City Building

Production Designer Craig Lathrop supplied blueBolt’s team with a large amount of concept art and reference for early 19th century Germany, and Robert Eggers had his own look book to communicate by example the look and feel he wanted, including colours and moods.

To create the fictitious city of Wisburg, Germany, where the story takes place, Craig studied and closely followed historical reference from the period. “He could be pretty certain that his decisions were accurate because many German towns still exist where older architecture has been preserved,” said David. “Lubeck, Germany was chosen as a reference town for how the streets were laid out – poorer areas against the richer ones, for instance, and the industrial areas. As Wisburg was a port town, it would need to include port neighbourhoods as well. We wanted it to make sense.”

To accommodate key aerial shots of Wisburg, they needed to have these specific locations set out as anchor points within the wider town plan, and build the complete town from there. Down on the ground with the characters, authentic sets were built for the main streets, the houses of the main characters the Hardings and the Hutters, and Count Orlok’s manor. BlueBolt built extensive digital environments for a number of shots captured on green screen and also some entirely CG shots.

The production sent a team out to various towns in both Poland and Germany to record full LIDAR scans of the streets as a start point for Wisburg, to make sure the views around the town were architecturally correct. Robert was also very aware of the risk of the buildings looking too neat and ‘perfect’. He wanted to see them leaning or sagging slightly, as they would in a real town, asymmetrical with non-parallel lines.

Cinematography – Light and Shadow

Because the cinematographer Jarin Blaschke and Robert had worked together previously, both on Robert’s first film The Witch and on The Northman, David and the team wanted to learn, as early on as possible, about how Jarin was planning to shoot and light the scenes. So, when they had completed the city up to the grey scale stage, Jaren visited them at the BlueBolt studio.

“We went through every shot with him that we would be working on. We quizzed him about how he would light certain scenes, about his lighting ratios and about the position of the moon,” David said. “We wanted to match everything about his cinematic style. We had some very long all-CG shots that eventually cut to his footage – but that transition had to be imperceptible, with no sudden jolt for the viewer. We had multiple meetings with Jaren throughout production, and often sent frames and questions to him asking for feedback.”

An interesting feature of Nosferatu is that the entire project was shot on film. For BlueBolt, that meant matching the look the stock gave the images. “It was important to match the response curve of the film in the shadows. Jaren is very sensitive to those details – he has an incredible eye. As light increases and decreases, the detail in the shadows of footage captured on film does not vary linearly, as it does in shadows captured digitally. The detail varies along a curve that turns down at the end as the scene darkens, losing detail quickly but still holding onto information in the shadows,” David noted.

Night Light

Jaren exposes the film specifically for that part of the curve. His techniques for lighting nighttime scenes had been developed for The Northman, and advanced further in Nosferatu. It was another topic that called for lots of back-and-forth discussion with the team to make sure they were capturing the light response correctly. “Jaren has a special lens filter that he uses for night shots, that cuts out most of the red light. At night, human eyes use rod-shaped photoreceptors. The rods can detect even very dim light, but not colours – notably red – which the cone-shaped receptors can see in daylight,” said David.

“For us, that meant following his unique way of working. We removed the red channel from our CG so that our response to the lighting was compatible with his images. It took time but we used our experience with this technique from The Northman.”

Jaren’s signature long shots were slow and deliberate, and the scenes carefully set-up – no fast moves. The average shot length was 800 frames, which is very long for VFX work. Typically, VFX work is done on shots of about 90 frames, but for Noseratu, their longest were 2,500 to 3,000 frames. The effect of this deliberate pace was the CG had to be perfect, with every detail precisely in place. David commented, “It was also a challenge for reviewing shots, which is a big part of my job. I had to be totally focussed and concentrate fully on that shot while checking every edge in our composites.”

Stitching Plates

A special challenge BlueBolt met to support those very long shots was stitching plates together in several sequences to overcome the limitations of the physical sets. Sometimes, when Robert wanted to achieve an especially long shot, the set construction prevented the crew from continuing their camera move. They would have to stop, redress the set, perhaps removing a wall temporarily, re-position the camera and let the actors pick up where they had left off. They might shoot 800 frames from one side of the set, and 500 from another angle.

David remarked, “By co-ordinating with Angela on set, she could make sure we had a feature in the foreground we could use to create a wipe-point connecting the A and B plates – like a lamp post or piece of furniture. If the cameras were at different heights, we might have to warp the image slightly, and if the shot took us from one room to the next, we would use a beam or edge of a wall to create a stitch that brings the two cameras together.”

An especially long, scary shot at the end of the film takes place inside Ellen Hutter’s house. It begins in her living room, and then we see Orlok’s shadow travelling along the wall, up the stairs and into the bedroom. Continuously following the shadow’s move gave the team four separate plates, three stitch points and 3,000 frames to manage without revealing any cuts.

“Robert really values the way shots like this can keep the audience on the edge of their seats,” said David. “It takes time and a lot of attention to detail to organise the shoot on set, while making sure that those invisible inter-shot connections will be possible to achieve with compositing. Occasionally we’ll need to recreate parts of the set and add a digital camera to fill in certain areas. This didn’t happen as much on Nosferatu as it did in Northman. We are learning, getting lots of practise.”

In the Blood

The Northman had given BlueBolt plenty of experience with blood and gore, which was obviously going to be a major element here. There was actually less of it in Nosferatu, but the challenges were different this time – extreme, perhaps, but always based in reality. When we see Orlok in scenes attacking and biting people in the neck, streams of blood were required to ramp up the fear and drama. Meanwhile thunder and lightning are raging outside, sometimes flooding a single frame with brilliant light in which everything can be clearly seen.

Toward the end, blood and gore pour from Orlok’s eyes and mouth as he dies. David said, “What we had in-camera, pouring from the mouth, was a practical effect and we created everything else to blend with that. The director wanted the blood running from the eyes to feel very real and tangible, as if it were right there on set with the characters. He wanted it to attract attention but not pull viewers away from the story. It was a matter of balance and thinking about how the blood would react to different levels of light, about its colour, viscosity and motion.”

Swarm

Deciding how to handle the rats that appear in this story was a kind of journey as well. When BlueBolt noticed the presence of a swarm of rats in the script, their initial advice was to create and animate them in CG. But in the middle of the shoot, Robert decided he wanted to capture the sets flooded with thousands of real rats. However, as they organised this and tried to get the shoot underway, they realised challenge of managing the creatures and went for a digital solution.

“While we had been noticing fewer and fewer rats appearing on set in the plates, Angela took full advantage of having the rats there and took abundant reference shots and stills of how they looked in the environment, and how they behaved as they ran around and swarmed,” said David.

“Back in the studio, we modelled a couple of rat variants and modelled the set. Then we created about 60 typical rat animations – running in different directions, stopping and sitting up, looking around and so on – and moved those into Golaem, the software we used to manage the swarming effects around and over the set. The result from that took us about 80% toward the look we wanted, so then we went in and manually adjusted the agents for collisions and other anomalies, especially in Robert’s longer shots.” (See the image at the top of this article.)

Shot by Shot

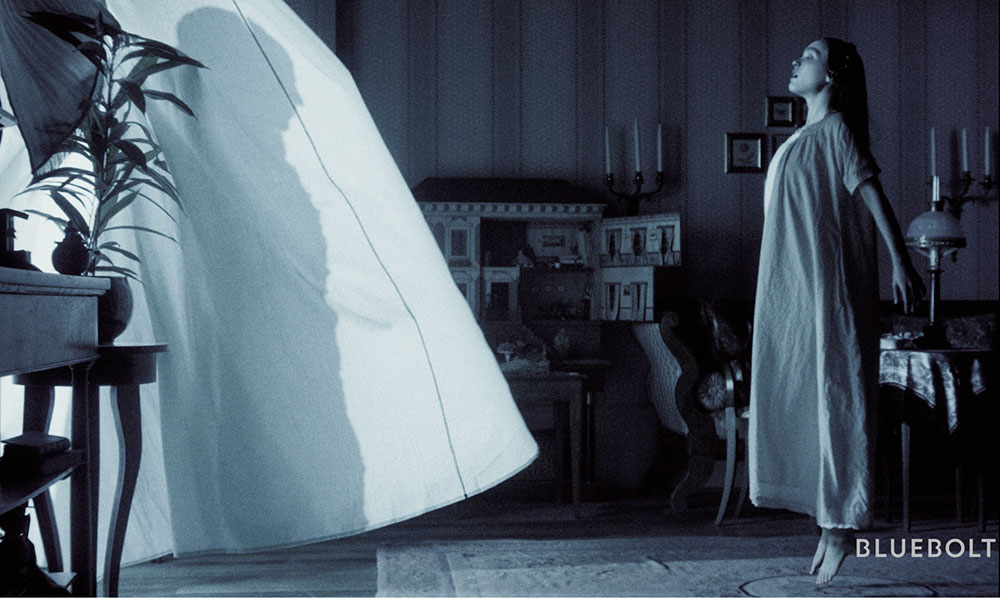

The shots that best evoke the fear, horror and drama Robert was looking for were sometimes the simplest. At one point, Orlock stands at the window behind a curtain, shot practically, where his distinctive shadow appears to be projected onto the cloth billowing in the night air. To incorporate the shadow in post, they tried to figure how it might distort realistically, and how far they could take that before losing the audience’s ability to recognise him – that is, recognition against realism. In the end, keeping it simple in compositing was the best approach.

A full-CG storytelling shot of a ship at sea in a violent storm shows Orlok on his journey to Wisburg. David talked through it, “Shots like this start out much like pre-vis, first built in grey scale, where Robert could check the speed of the ship, the layout and distances between elements, and the shot length – before we went too far. Then we could think about lighting the whole scene and consult Jaren the DP about the position and brightness of the moon. Finally a matte painting was created for the stormy background.“

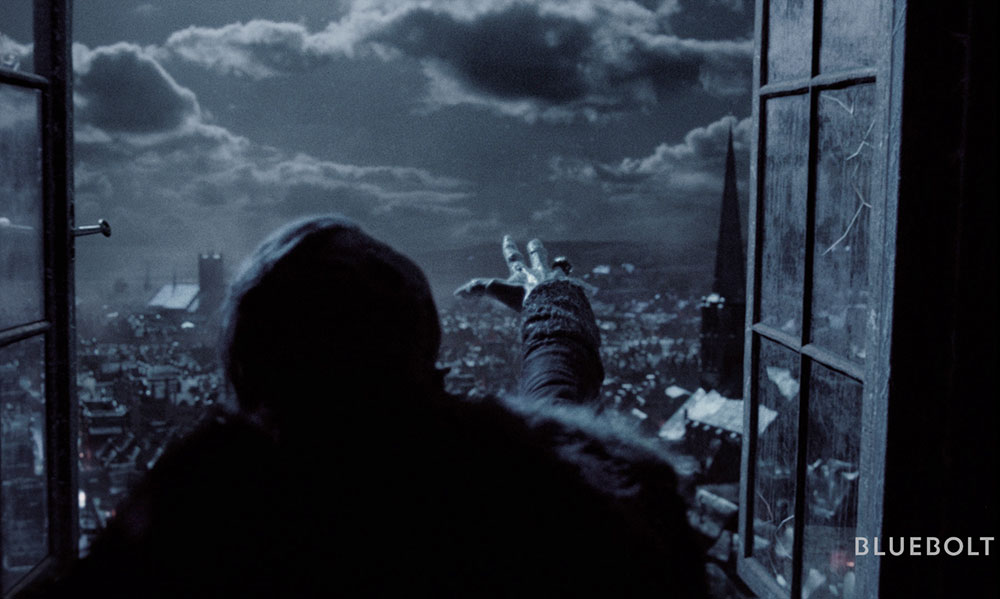

A High Bar

Setting a high bar for the VFX in this film has brought reactions from from audiences as well as critics that David is very pleased about. He said, “In the wide publicity Nosferatu has received, there has been no real mention of visual effects, not even about the huge, menacing shadow of Orlok’s hand seen passing over Wisburg – that’s a 900 frame shot of a city we built from CG assets, not a digital matte painting. This shot features in all the trailers and promos, blending directly into the director’s storytelling, and it’s tremendously satisfying that no one has singled it out as a VFX shot. That’s exactly the response we want.”

As the director described it himself, "I have nothing but praise for my collaboration with BlueBolt. Their trademarks are photorealism, naturalism and subtlety – not maximalism,” Robert said. “Their attention to detail is impeccable as well as the drive to never finish until the work is as close to perfection as possible. Above all, BlueBolt's commitment is to telling great stories. I look forward to working with them again on the next one." www.blue-bolt.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor