Digital Domain’s Animation Supervisor Liz Bernard talks about her team’s work on a massive population of cubic characters – designing motion, following rules and leading them into battle.

Senior Animation Supervisor at Digital Domain Liz Bernard had just wrapped her team’s work on The Electric State, after working on the production’s characters for two years, when she was asked to lead a team for A Minecraft Movie. This new project called on her team of 28 animators to jump into a squared-off world and get to know a massive population of cubic characters. They also needed to learn the rules their designs and motion had to follow to navigate the Minecraft universe.

Digital Domain’s artists joined the project toward the end of post production – leaving them just 25 weeks to create 187 custom VFX shots across 11 sequences – by which time a number of the character assets the animators were to work on had already been designed at Weta FX, including the huge population of Piglins. The dog characters and wolf variants still needed further design work, while the Golems were already designed – except for the gamers’ favourite, Super Iron Golem. “This giant was all Digital Domain’s effort,” Liz said.

A Few Restrictions

“What made the animation on all of these characters interesting was that it involved a range of restrictions. The design of the Piglins, for instance, prevented raising their arms very high due to the large bulk of their heads, and their short necks allowed very little head rotation.”

Human motion capture formed the basis of their performances, but when it came to retargeting the motion onto the models and animating the Piglins to work in their sequences, intersections often occurred between parts of the body. That meant the animators had to stop and refine the moves, holding up the free flow of motion.

True to their in-game equivalents, the Golems were rigid iron blocks without much scope for bending. “But they still needed to perform,” said Liz. “Here, intersections were a considerable stumbling block due to the sharp, angular corners and edges of the limbs at the joints that interfered with natural-looking moves.

“For those cases, we developed an innovation in the rigging that ‘exploded’ the limbs apart somewhat, allowing them to move as required while preserving the relationships between them, without having to add awkward pieces to the body.”

Mathematical Grid

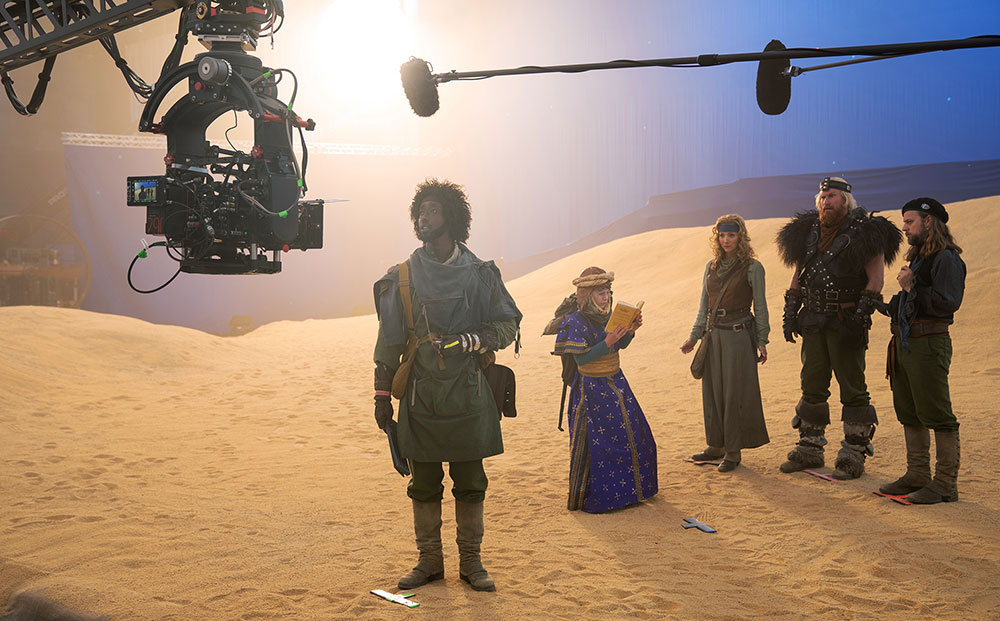

The overall layout within the frames needed to adhere to a mathematical grid design and theory – the foundation of the Minecraft world. Nevertheless, the production’s priority for the scenes and environments was to ensure that they look as beautiful as they are coherent. Therefore, for the director Jared Hess, visualising this world as production progressed was essential.

Not only were a collection of physical props and set pieces built, but pre-vis, post-vis and virtual techniques were developed and continuously updated as well, an approach that benefited the whole production – from Jared and the DP Enrique Chediak to the actors, visual effects artists and animators.

The Virtual Art Department (VAD) played an important role. In Unreal Engine, the practical sets were developed into complete 360° 3D environments, which allowed everyone to see how the materials and textures would look in the final movie, and the lighting could be designed. From there, the Unreal scenes were used in various ways from planning and reviews to blocking shots with the actors and camera operators. They also helped determine the best balance between digital and practical sets before building got underway.

Evolving with the Landscape

Because LIDAR scans had been recorded of the physical sets, the VAD was able to align them precisely with the virtual assets. This was important to make sure they would work with virtual camera tracking – Jared worked with a virtual reality presentation of the environments that he could view with a headset to ‘walk through’ the Minecraft world and make decisions about camera angles, the scaling and overall layout in upcoming iterations.

The environment artists had built these Unreal scenes in a modular way to allow continuous adaptation, which was an advantage not only for Jared but also for the VFX and animation teams. For Digital Domain, a very useful aspect of this 3D kind of visualisation was that it kept them informed of how well their characters were working with the environment design.

Liz said, “The Golems themselves, for instance, were built on architectural principles and needed to fit in with the landscape. It was also interesting to work with the faceted nature of all of the character designs, which made lighting a key issue as they moved around, relative to the light sources.”

Live Action Meets Virtual

Because the live action characters were walking through the environments and interacting with creatures and elements and disrupted the geometrical design, the artists introduced occasional organic shapes – like rounded pebbles and more natural looking plants – into the scenery to help form a visual ‘bridge’ to the human actors. The small fires scattered through the scenes created interactive lighting and added warmth to the shots as well.

While adhering to Minecraft’s rules was important, the production was keen to introduce a lot of silliness into the visuals for this film. “Jared our director, with his signature sense of humour liked taking advantage of fun, unexpected quirks in the story and characters as a source of humour. The story was pretty simple, and because we weren’t striving for strict realism, continuity across the project was a little looser than usual.”

They also had the opportunity to introduce a great variety of gags throughout the scenes, taking their characters to the extremes of what their rigs and models could accomplish. Because the characters’ anatomy was clearly linked to the motivations for their actions, animation reference was varied.

In – and Out – of Character

For the Golems, for example, movement had to maintain the architectural theme and stick to the rules of rigidity, but to interact effectively with the Piglins, the animators needed to add a feeling of weight. So, when attacking, a Golem moves toward the Piglin, swings its arms up violently, and flings the pig’s body into the air. Piglins are heavy and the distinctive arm swing the Golems use to do this needed some bounce to look convincing.

Fortunately, other characters could refer to something more familiar. Digital Domain could turn to real dog reference for the wolves, and the Piglins themselves had the more organic pig animation style created at Weta. “However, as mentioned, the team could put a lot of their own creativity into the Great Hog. Our reference here included gorillas, which you see in the way he leans into his shoulders and back for ambulation.

Super Iron Golem

Likewise, the Super Iron Golem was a chance for the the team to have some fun with these characters. He was designed to be physically about 35% larger than the other golems so that he would really stand out in the battle scenes, and, of course, he had fancy armour whereas the regular golems were adorned with vines.

Liz described him in detail. “When the character Henry crafted the Super G, he used the boots of swiftness from player-character Steve's stash, and so that also became part of the armour,” she said. “The boots were winged, Hermes-style, and gave the Super G super speed and the ability to jump extremely high when he powered them up. Because this character had similar physical limitations to the regular golems, and was also made of stiff blocks that could not bend, making him run with that super speed was a challenge.

“So, we put a lot of thought into the design of the boots, adding small panels and flaps to help maintain the boot's angular silhouette without bending or warping the blocks that made up each boot. We kept the run itself pretty stiff legged to keep it in character, and increased the stride length to give him a run that looked a little more like a cross-country ski stride than a standard sprint.”

Battling It Out

The great battle scene was Digital Domain’s most complex challenge in this project. The huge number of characters meant that organization was key. Using spreadsheets, the Animation team set out the details for 10 base characters (Piglins and Golems), each with two to five costumes, eight to ten different weapons and a range of 20 to 25 actions per character. “All of these options added up to a massive population of variant characters and potential actions,” said Liz.

“Our Crowds team used these to generate our crowd simulations using Autodesk's Golaem crowd software, in which we could set parameters to have characters avoid one another or environmental obstacles, conform to the ground plane, and interact with other characters as needed.

“The battlefield itself had come from Weta, which they supplied with the ground plane already established. Having that feature firmly in place in such a dynamic environment meant we could push ahead and begin refining the animation early on instead of waiting for the ground plane to be finalised.”

Battle Vignettes

The 360° virtual environment came into its own for this battle scene, because Jared could map out the level and kind of action he wanted for the different camera angles, giving the animators a plan to work from. To keep ahead of the game, they created a series of ‘battle vignettes’ in advance.

“A typical one would be an Iron Golem fighting with three or four piglins,” Liz said. “While we needed to create and animate hero characters for the foregrounds, the vignettes proved very useful for filling out the midground and meant doing less last-minute animation. It was another technique we devised to allow ourselves enough time to perfect our character performances and interactions.” digitaldomain.com