VFX Supervisor David Schneider at Union talks about digitally recreating the vast concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, an evolving project that required the delivery of nearly 200 shots.

For the TV series The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Union VFX in London undertook the digital reconstruction of the vast concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where over a million Jews were murdered. This large-scale project required the creation of 38 assets and the delivery of nearly 200 shots.

The series portrays the story of two Jewish people, deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau during World War 2. After he arrives there, young Lali is recruited as one of the camp’s tattooists and put to work inking identification numbers onto fellow prisoners’ arms. One day, he meets Gita when tattooing her number on her arm, leading to an unexpected, life-long love affair that contrasts sharply with the events unfolding around them

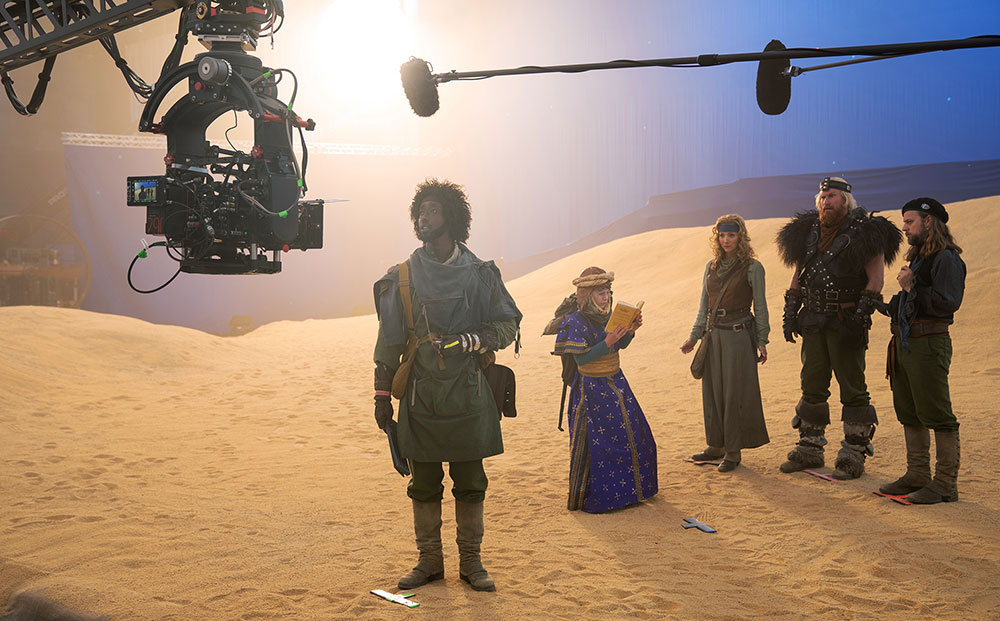

The visual effects for the project were divided between two studios – Union and Untold Studios. Union led the work on environment builds and atmospheric FX, while Untold focused primarily on story-specific character effects such as tattooing, prisoner emaciation and body replacements, with some contributions to environment work.

Discussions between Union and production company Synchronicity Films began in early 2023, and Union’s work commenced shortly after the shoot concluded. The team was led by VFX Supervisor David Schneider, with 2D Supervisor Dan Victoire and VFX Producer Tallulah Baker.

Authenticity

Union’s primary production collaborators from Synchronicity were VFX Supervising Producer Alan Church and VFX Production Supervisor Simon Giles. Going beyond a straightforward camp build, the team developed vast, complex CG environments using techniques that allowed them to accurately and interactively depict the camp’s expansion as the story progresses.

Historical authenticity was critical throughout the project. With 70 artists working across 14 departments, Union undertook detailed research into textures and weathering for their 3D assets, as well as the surrounding area for digital matte paintings used to extend wider shots. They also handled dynamic visual effects and atmospherics, including fire, smoke, dust and weather. A range of background characters – both 2D and 3D – including prisoners, guards, and officers, was also built to populate various types of shots and add depth and realism.

Telling the Story in a New Way

Key reference material included a full collection of historical photos of Auschwitz. But the production wanted to present a view of the camp and life inside it that had never been seen before. “All of us were aware that the historians and photojournalists of that time had to work within the constraints imposed by the equipment and opportunities available to them. The camera angles and scales we can capture now enable filmmakers to tell the story in a new way,” said Union’s David Schneider.

The Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp, where the story is set, was truly massive. It was a secondary and much larger camp located a few kilometres from the original. Because the structures were under construction during the course of the series, the work amounted to a large-scale building project that Union successfully visualised as a feature of the story.

“Our team relied heavily on photography from the site, both historical and modern. Alan Church had delved into the history of the time and place,” David said. “Synchronicity Films also hired a historical advisor who provided detailed reference materials. Since the practical set was slightly smaller than the actual camp, we began with a lidar scan of the set, adjusted the original camp blueprints accordingly, and laid out our environment so that the digital set extension matched in proportion.”

The Expanding Camp

Mobile greenscreens, mounted on two large trucks, could be driven around the set to wherever the production was planning to build set extensions – for instance, to show the long rows of barracks receding into the distance. The greenscreen could also be used for element and background character shoots right on site, allowing the team to capture accurate lighting, camera angles, and other contextual details.

The layout phase, led by CG Lead Chris Davis, was handled in Houdini. “At Union, we use a USD-based CG pipeline. Houdini Solaris enables us to lay out the vast camp efficiently using the USD system,” David explained. “USD allows primitives to include multiple variants—options for different sizes, styles, and configurations—on a single asset. The layout and lighting artists can choose between variant sets and activate the desired one at render time or while constructing the scene.

“For example, a new variant could be created by picking up a part of the camp that was behind the camera in one shot, moving it around, and placing it in front of the camera in another—similar to picking up a structure built of Lego bricks. Since the physical set was used to represent various parts of the camp, we could reconfigure the digital set extension to suit the sequence.”

Interactive Deconstruction

“One very high-quality barrack was built in which almost everything was adjustable, from the positions of the doors on their hinges to the barrack’s state of completeness as the story progressed through different stages of construction. Our artists added or removed wooden planks and frameworks and varied the completeness of the roofs in 10% increments. Using the software’s variant system meant we could keep the base asset full of options to give the artists as much flexibility as possible as they worked.”

They thought of this kind of work as ‘interactive deconstruction’. When Lali stood on the roof of one of the buildings and surveyed the work in progress, for example, they could adjust the barrack variants to allow a view down into buildings with partial roofs—or no roof at all.

Only a few all-CG shots were needed. The production’s practical set was impressive, and Union’s work had to match it invisibly. In post, the digital set was dressed with 2D and 3D elements, and the compositing team layered in dirt and grime. Avoiding repetition was a priority. The Solaris software’s ability to introduce randomness supported this: layouts could be subtly shifted, and the angles or positions of objects slightly varied.

Atmosphere and Sky

Atmospherics were important in conveying the harshness of the camp and required a diverse mix of techniques. “Dust especially is ever-present, and could be added as 2D elements for extra realism,” David commented. “Snow, on the other hand, was often applied in CG layers to enhance the practical snow placed on the set, using 2D elements whenever it came close to camera. The fire and smoke pouring out from the crematorium chimneys was usually generated as an all-CG effect, which resulted in better volume and control.”

Union was responsible for replacing many of the skies with digital matte paintings. David noted that while the real skies captured on location were often quite beautiful, they sometimes had to be extended or replaced, particularly when the surrounding forest line was altered or removed. “Some shots required full sky replacements for storytelling or continuity purposes,” he explained, “while others retained the natural skies we captured during filming.”

Human Figures

Within the camp environment, human figures are always visible in the background—moving around, entering and exiting buildings, working, and interacting. The Union team managed three sources of background characters, depending on the shot. The first and most common method was greenscreen shoots of extras in costume, engaged in various activities. Others could be extracted from plates and repeated—a technique used sparingly in aerial shots, with attention to varying camera angles.

The third option, used less frequently, involved creating 3D digital doubles. These were especially useful for drone shots, which were often captured from angles too high to work effectively with 2D elements. One such example occurs when the camp begins to descend into chaos, with people moving in all directions.

The Tattooist of Auschwitz is a profoundly emotional story, and a deep sense of that emotion was felt behind the scenes as well. Synchronicity Films’ VFX Supervising Producer Alan Church sadly passed away at the end of 2024. Alan had played an essential role in guiding the visual effects work, and his dedication, warmth and collaborative spirit were central to the strong relationships formed between the teams at Union VFX, Untold Studios and Synchronicity. His sudden loss was deeply felt across the production. The series and its success stand as a testament to his leadership and the care he brought to every aspect of the project. www.unionvfx.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor