Glenn Melenhorst, Dom Hellier and Nick Tripodi at Framestore in Melbourne talk about building a cast of dragons to live, emote and bring their magic to the real world.

An expansive team of artists, producers and technologists at Framestore, located around the world in London, Montreal, Melbourne and Mumbai, worked on this year’s live action film How To Train Your Dragon for two and a half years. Led by Production VFX Supervisor Christian Mänz, Framestore worked alongside the production crew, handling concept art, visual development, previs, techvis and postvis, all leading to the delivery of 1,400 VFX shots.

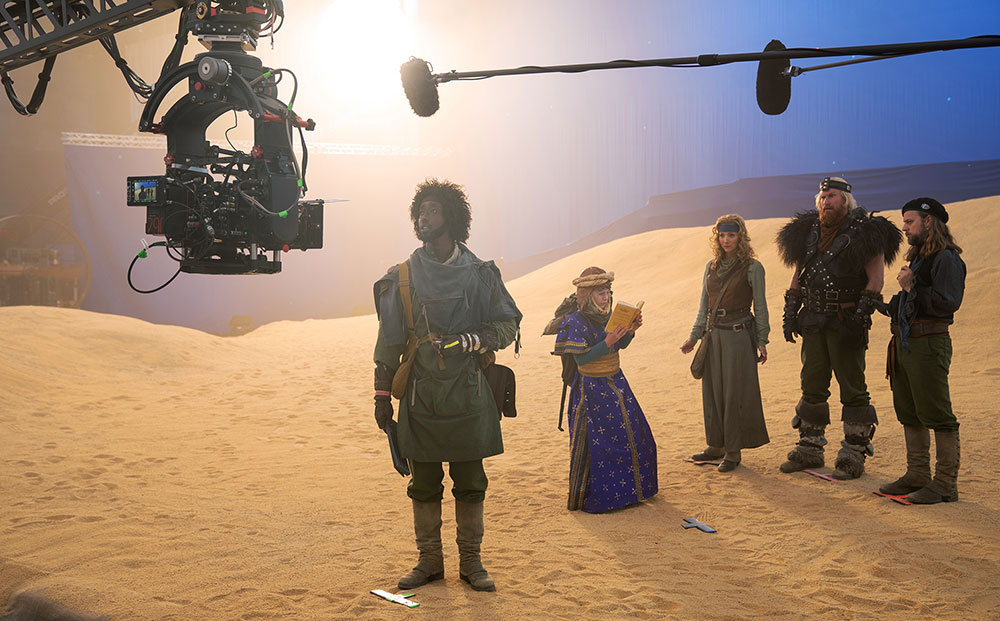

Visualising Toothless and the film’s cast of dragons, and realising their performances, was achieved through keyframe animation. Puppetry was used on set to enhance the actors’ interactions with the dragons which, in turn, helped the animators express subtle emotions in the dragons.

Digital Media World spoke with the Melbourne VFX team who worked on the training sequences inside the arena. Here, the audience meets the young dragon hunters – and the dragons themselves – up close. The artists’ work became an essential part of the whole filmmaking process, blending invisibly with the sets and production design, special effects and puppetry, and the cast of actors.

From Animation to Live Action

Director Dean DeBlois was already committed to Toothless and his fellow dragons in their original form from the earlier, animated films. Therefore, Framestore VFX Supervisor Glenn Melenhorst saw his team’s main challenge on the project as translating them into characters in the real world, while retaining what had made them so compelling to audiences.

“The dragons are long-established and loved by a huge fanbase, many of whom know every detail about them, so earning the fans’ trust meant portraying the dragon characters exactly right. It meant more than just updating their look,” Glenn said. “Their physical appearance needed to evolve to sit naturally within a live-action world but, just as importantly, their performance had to change, too.

“They needed to move with the weight, musculature and grounded interaction of real animals, yet still keep their original charm and expressiveness. Finding those hooks and bringing that to their performance was key to making these dragons feel both authentic and alive, as well as earning the trust of the audience.

Animation Understanding

Dom Hellier, also working as VFX Supervisor, said, “From the outset, Dean provided us with the clearest of briefs for the project, aspects from the original film that he wanted to stay true to, and what he wanted to tweak or change. Beyond that, his intimate knowledge of the creatures and the story was so important for conveying each dragon’s character and really helped us quickly get to the point of subtle refinements and details.

Glenn commented on the benefits of working with a director who truly understands animation. “Dean knows the process and evolution of a shot through the pipeline, and can look at the work at various stages with an informed eye, understanding what’s still to come,” he said. “Directors with animation backgrounds, like Dean, tend to plan what they shoot and shoot what they plan, which is critical in a medium as complex and painstaking as animation.”

Dean was their primary resource when it came to understanding the dragons. By working alongside him, they found those subtle beats in their performances, highlighting those idiosyncrasies that would bring their unique personalities to life. “The real joy was in discovering those little moments between the big physical moves that made the dragons feel familiar and full of character,” Glenn said.

Reference

For reference, apart from Dean, each dragon had a set of real life creatures the animators attributed certain characteristics to. Animation Supervisor Nick Tripodi said, “For instance, the Gronckle was a combination of a bee and a slobbery, clumsy bulldog. Another example was the Terrible Terror, which used lizard and meerkat references.

“We used an interesting piece of reference when the Deadly Nadder is tangled up in the broken pieces of the maze walls – reference of a shark thrashing about in a boat to impart the sense of dangerous chaos.”

Nick also remarked that having a well organised library of reference really paid dividends when they were in the heat of production. “Reference was filed against specific dragons they relate to, then the type of animal being referenced, and lastly the action or emotion. This allowed animators to quickly hone in on a desired performance reference. We would often collage or edit together multiple references to create a more complex performance idea. This approach allowed the Supervisors and clients alike to see and sign off on proposed ideas for shots before we invested time into keyframing.”

Creature FX

Toothless, with his large beautiful eyes, has a wonderful capacity to express emotion. “In contrast, the rest of the dragon ensemble has limited facial controls, or at least small eyes and brows that made conveying their emotions more of a challenge,” Glenn said. “With such a limited palette to draw on, we relied heavily on body acting, with clear staging, to show the dragon’s thinking.

“Using reference of birds for the Nadder, animals like bulldogs for the Gronckle, geckos for the Terrible Terror and crocodiles for the Monstrous Nightmare helped in differentiating them from one another and we combined those animal traits with ‘acting’ beats to make each dragon feel distinct.

“Apart from Toothless, the Gronckle seems to be a fan favourite – or at least I have a soft spot for her. Animating her was fun because she was so boldly comic in the original films, and we got to expand on that, adding real weight and dynamics to her as she thumped and crashed into everything in the arena.”

Nick especially enjoyed bringing the Deadly Nadder to life in the maze training sequence, bringing a sense of a huge, twitchy, bird-like dragon trying to navigate a maze that it can barely fit into. “It was so fun to create this mad, messy scramble,” he said.

Predator

“The Monstrous Nightmare, on the other hand, had to feel like an incredibly dangerous and aggressive predator. Looking at serpents and birds of prey for reference, we wanted to show off the Monstrous Nightmare’s lethal capabilities. This culminates in the final trial test for Hiccup in which we get to see just how fearsome and perilous it is to face such a creature.”

With features and movements based on a crocodile, the Nightmare was confined within the arena environment the team had built, where the tight, cramped space emphasises its bulk and the element of danger.

Dom said, “We used the arena to show how ill-adapted the dragons are to where they’re being held captive – but it also presented a challenge in terms of conveying the right level of threat and menace. We made sure every creeping moment and every strained flex of the wings felt plausible.”

The Monstrous Nightmare was also able to excrete and breathe a liquid Napalm-like fire, requiring heavy simulation work. Its breath resembled a flamethrower, other types of fire dripped from its scales and wings, magma glowed between its scales, and ground fire burned around its feet. Each of these required its own specific simulation and, in turn, each one affected other simulated elements like the dust on the ground and the wind blowing through the arena.

Production

Steps were taken on set during filming to pull the dragons into the actors’ performances, although they couldn’t actually be there. With their dragon props, the puppetry team played a crucial role on set by giving the dragons a physical presence that allowed the actors to interact with them while visualising the final image. It gave the production, animators and compositors a feeling for their scale within the environment, as well as many other clues for integrating the creatures into the movie’s world.

As well as giving the actors an ideal eyeline, the stand-in puppetry heads helped place the dragons into any shots where they interacted with humans. Capturing the heads in the shots also meant lighting information was recorded for the team and cast real world shadows and occlusion onto the actors and the environment. Occasionally the heads were walked (or rather run) through frame to help the on-set crew frame up the action, but often the dragons were taller in frame than a puppeteer could hold their heads, so they were used mainly as a guide.

Sequence Building

With this distinctive set of creature characters and their performances now clearly defined, building out the training sequences could get underway. In terms of environment, building Berk and the training arena and then blending them into the photography was an enormous challenge for every department.

Glenn said, “Creating fully digital environments that cut directly with environments captured in-camera means the audience can see reality and our work side by side. Our environments team sculpted rock-faces and boulders and vegetation to match the various layers that Dean, DOP Bill Pope, Production VFX Supervisor Christian Mänz and their crew had captured from their on-location recces. We were often borrowing elements from different real-world places to help blend the disparate locations with our digital world.

“The training arena was a great physical set. All the doors were as heavy as they looked and there was detail everywhere. We recreated the entire set in CG, building from scans for occasions when we needed to replace the on set photography. For example, if we had to paint out a barricade because the Nadder interfered with it, we needed to reveal those parts of the arena in CG in the background.”

The team also added the heavy chain netting above the arena and the towering cave aperture that the arena was nested inside. The set was built at the Belfast studios and, because it was open to the air on all sides, they used the digital set to shadow parts of the plate that should have been shaded by the cliff face. Some crowd replacement and enhancements were also required, turning the on-set crowd into a larger gathering for the final trial.

Interactive Moments

Dom noted, “We had some great SFX elements to work with in the shots, such as fire and sparks impacts for moments when the Dragons were breathing fire in the arena, as well as some stunt rigs for big interactive moments, such as the Gronckle lifting Gobber off the ground by his prosthetic arm.”

In fact, Gobber’s arm and peg-leg were replaced for many of the shots, scanning and building both the actor and the many replacement prosthetics he wore during the film. This meant painting out his real limbs and their shadows and reflections, replacing them digitally and blending them into the photography.

“Aside from Gobber's prosthetic limbs, another fun moment was replacing Tuffnut's hands and nose for his up-close-and-personal wrestle with the Terrible Terror. Although the performance in-camera was already great, taking over those aspects digitally allowed us to push the animation of the Terrible Terror further to enhance the action and comedy of that moment,” said Dom.

Bringing It All Together

Dom also remarked that the compositing work in the movie was critical to allow the dragons to appear to just be there with the people in the shots. “Achieving well-integrated composites began with meticulously planned and captured photography. The compositing team benefited hugely from the work of the puppeteers and practical SFX, which served as excellent in-camera elements that the artists augmented to integrate the dragons' interactions with both the cast and the set. We consistently sought opportunities to layer and interweave our CG additions with live-action plates, and to incorporate effects that enhanced the believability of contact between the dragons and their environment.

“Another compositing consideration for the training arena sequences was that we were digitally adding a giant cliff overhang – plus some enormous dragons – to the scene which, as Glenn mentioned, greatly impacts the lighting of the environment. As a result, the team often had to remove lens flares and directional lighting where it was no longer appropriate, as well as integrating shadows from the CG additions.

“Ultimately, the success hinged on the dedicated efforts of the entire compositing team—artists, leads, and supervisors—who, as always, went above and beyond to ensure that all edge work, focus levels and other integration techniques were executed to the highest possible standard.” www.framestore.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor

Images: Universal Pictures / Framestore