DoP Don Burgess, VFX supervisor Kevin Baillie and colourist Maxine Gervais pulled their talents together to create a world for the non-linear story of ‘Here’, shot from a single camera’s POV.

The recent movie Here depicts the lifetime of a married couple in America. It uses a number of interesting cinematic and visual techniques that go beyond the AI-assisted ageing and de-ageing process that attracted so much attention at the production’s release. For a start, the film was shot from one camera position and angle while the story shifts back and forth in time, a filmmaking style that resulted in some unusual challenges for the production and post team.

Working with director Robert Zemeckis, the cinematographer was Don Burgess, Kevin Baillie was VFX supervisor and Harbor’s senior colourist Maxine Gervais looked after the grade. They are a team that has had considerable experience working together. Maxine and Don Burgess first collaborated in 2010 on The Book of Eli, and Maxine, Kevin, Don and Robert Zemeckis’s team also worked together on Welcome to Marwen (2018) and The Witches (2020).

Maxine commented that, despite the single point of view and absence of camera moves, none of them anticipated that the production was going to be easy. She described the way her colleagues worked together. “Don and Kevin are so efficient at executing Zemeckis’ visions – they are a well-oiled machine. They are very creative in finding new ways to do things that haven’t been done before. Kevin is one of a kind, always pushing boundaries and ahead of his time for sure – he and Don work in harmony.”

Camera and Lens Testing

As cinematographer, Don Burgess began concept discussions and camera and lens test shoots in June 2022, conferring throughout with Maxine, Kevin and the director. He said, “Early on Bob Zemeckis expressed the idea of locking off the camera and shooting from one position on Earth. Most of the movie happens in the hero house, plus some scenes that occur at that spot before the house was built, or when we see the house fade in as characters enter it. But even while the set was still in design, we had a good idea of the size, where the window and front door would be and so on.

“It took many hours of trial and error to find the perfect spot to tell the story from. We had to talk through and test every scene before we started shooting. The lighting was designed for every hour of the day and every day of the year. We also talked over the weather with Bob – will there be cloud, sun, rain, sleet or snow? Once again, it was all worked out before we started shooting.”

Following thorough testing, he decided to shoot on the RED Raptor Camera with Panavision 35mm P70 series lenses.

Script, VFX and Production

Because the storytelling was going to depend so heavily on visual effects, Kevin Baillie was also part of very early discussions, before Robert Zemeckis and Eric Roth had even finished writing the script. “Different directors deal with visual effects in different ways, and Bob happens to be one that considers the effects as a key component of the process,” Kevin said. “This is not only fortunate and fun, but it also allows us to plan how best to shoot the movie.

“Often, people think of VFX merely as a process that happens in post, whereas really good visual effects are considered a tool to use throughout the course of production – especially when you’re doing something new or extensive like we were for this film. We had about 43 scripted minutes of de-aging that went as far requiring a full digital face replacement of our four lead actors, eventually expanding to 53 minutes in the final film.”

Kevin and his team were aware that accomplishing this work through traditional CGI face replacement techniques wasn’t feasible, due to time and cost constraints. They also realised that maintaining consistent quality over such an extended screen time would be very difficult, and decided to investigate their options for using machine learning and AI-based techniques. Kevin said, “We spent time doing the necessary diligence to figure out what techniques would work and what vendors we could partner with – something that we absolutely had to do before the shoot.”

Virtual Production at Pinewood

The team shot the interior of the house on two sound stages at Pinewood Studios. The window exterior was an LED wall, used to project images portraying over 80 different eras, weathers and times of day in the neighbourhood.

“The LED wall required a lot of prep work,” said Kevin. “We used Unreal Engine to create the world seen through the window outside as a real-time environment. This meant that Don could adjust the lighting to match the time of day or weather of the part of the story he was shooting. He could then adjust his practical lights inside to match what was happening outside.

“Most of the shots had the LED wall showing as the exterior background out the window,” Don noted. “The wall performed best at a cool colour temperature, so we set up the camera at 1600 ASA, 4300K and exposed at T5.6. The LUT was set up on set with Maxine and our DIT, Chris Bolton.”

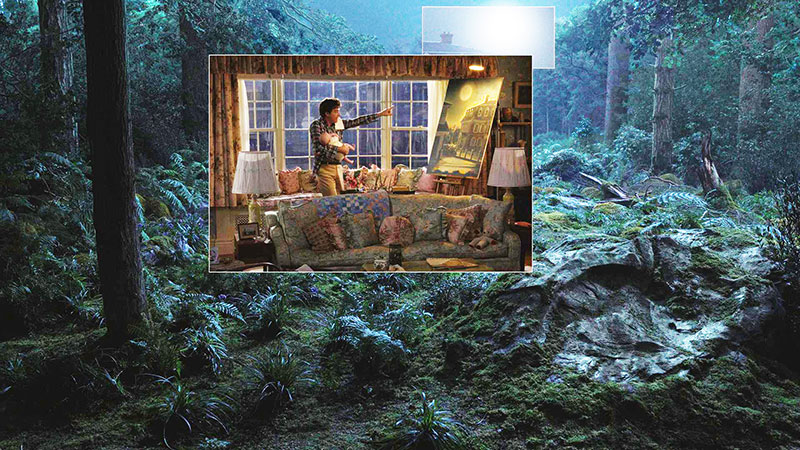

The story was adopted from a graphic novel by Richard McGuire, in which the frequent use of panels produces a picture-in-picture effect. The panels separate time from place – showing different scenes at different times of day or periods in time, happening in the same place.

“Twists in the fabric of space and time … 1964 from McGuire’s Here” (source: The Guardian)

The director wanted to use this same graphic novel/comic book iconography for the film, which brought specific challenges for the team.

“The transitions between scenes were primarily done through graphic panels, in the style of the original graphic novel,” Kevin said. “We could have multiple scenes playing on screen at any one time and juxtapose two separate moments that were spiritually or thematically ‘connected’ – which is something that you can't really do in a traditional live action movie.

Neat Nuke Workflow

“The process of creating and designing those panels involved bringing in my friend Dav Rauch, a graphic design genius who was one of the original designers of the Iron Man Heads-Up Display, in the first Iron Man film. When I invited him to help us work on these transitions and ‘design some boxes’, he jumped at the chance to work with Bob and use a simple looking design language to do something very creatively nuanced.”

The team set up a system that integrated the panel work with editorial – Dav would work on a machine in the editing room with After Effects and collaborate with Robert and the editor Jesse Goldsmith to create the graphic panel transitions. Those approved transitions would then be fed into Avid, where they would recreate them. Going through this process meant they could maintain editorial flexibility without having to do the graphic design work within Avid, which would have been fairly cumbersome.

“Once those were signed off, we assembled an in-house team led by Compositing Supervisor Woei Lee to do the graphic panel transitions as a visual effects task,” Kevin said. “Because some of the panels required layering in front of or behind live-action elements in shots, our compositing team was able to do some very cool, subtle effects with the transitions in Nuke.

“You don't see them on the screen, but the graphic panel team also provided detailed, labelled masks for every single transition in the film, which gave Maxine and her colour team the ability to consistently treat the colour of not just the shot on its own, but the shot as it transitions through an outgoing panel and into the next shot.

“There were mattes for every border of every panel and, since some of these transitions have over 20 different scenes that go into a single transition, each one was quite the logistical challenge to both create in the Nuke workflow as well as to manage in the DI.”

Building the Colour Timeline

Maxine was handed these mattes to isolate all the panels for colour grading. However, sometimes she had multiple panels showing the same scene, which needed to be graded the same way, and these would fade in and out at different times or be cross-dissolved with other scenes – which would need to be graded differently.

“Not only did we have to find a way to deconstruct and rebuild the shot into their panels using mattes, but there were also mattes within mattes,” Maxine said. “This meant that if I wanted to colour a panel to match its full screen before transitions, and the full screen used mattes for windows or different elements, these same mattes needed to carry these colour tweaks within the panel themselves – and then carry on and blend or dissolve invisibly into the transition.”

Managing Director of FilmLight in the US Peter Postma dedicated a few days at the beginning of the process to help Maxine work out the most efficient way to build the timeline in the Baselight grading system she was working on. They aimed to help her focus on the grading without constantly having to copy grades around between the panels every time a change was made.

“The challenges that grading Here presented to us, forced us to rethink how Baselight’s features could be used to improve the grading experience,” Peter said. “It was great working with Maxine and her team to gain a better understanding of what our tools are capable of meet those creative challenges.”

Maxine reflected, “Let’s just say the workflow was very complex and needed a lot of organising and labelling. I had never had such complex timelines before, but thanks to our talented team we were able to make it happen.”

Connected Scenes

Again, because VFX was so integral to the movie, Kevin was also a part of the colour process. He sat with Don and Maxine to create initial colour passes of all these scenes, which became a challenge because every scene is connected. Kevin said. “If one scene isn't done, the next scene and the scene before it also can't be finished. That meant that the colour timeline remained open until very late in the process, and meanwhile we tried to make choices along the way with unfinished visual effects.

“Contrary to our expectations, the static camera actually made everything much more difficult – we had nowhere to hide in this film. But, once we had the full movie in place, we went through it many times trying our best to spot everything that still had to be addressed.”

“The final colour and the nuance really ended up as a team effort – driven by Don Burgess with the hands-on done by Maxine, and with me making sure the visual effects were doing what they were supposed to do.”

Maxine also used several Baselight features to support creative and technical goals. “I used everything at my disposal in order to make this work,” she said. “Thankfully, Baselight has its own long list of very effective compositing tools like grid warp, painting tools, texture tools and blending tools. They were not only necessary to make this project happen, but also a great help for the VFX team, through the effects work we could contribute in the DI.

Opportunity

“I can only humbly say that I am very grateful for such an opportunity,” said Maxine. “Although Don has a long history with Panavision, I’m lucky to have had these few projects where colour wasn’t just an artistic goal, but often a technical challenge.”

Don remarked, “Bob created a unique way of telling the story, which became visually challenging for me, and that made it very exciting to collaborate with Maxine to bring it to the big screen.” Kevin agreed, saying, “When Bob came to review the work that we prepared for him, he was extremely satisfied and had almost no notes – which is always the best compliment that you can ask for.” www.filmlight.ltd.uk