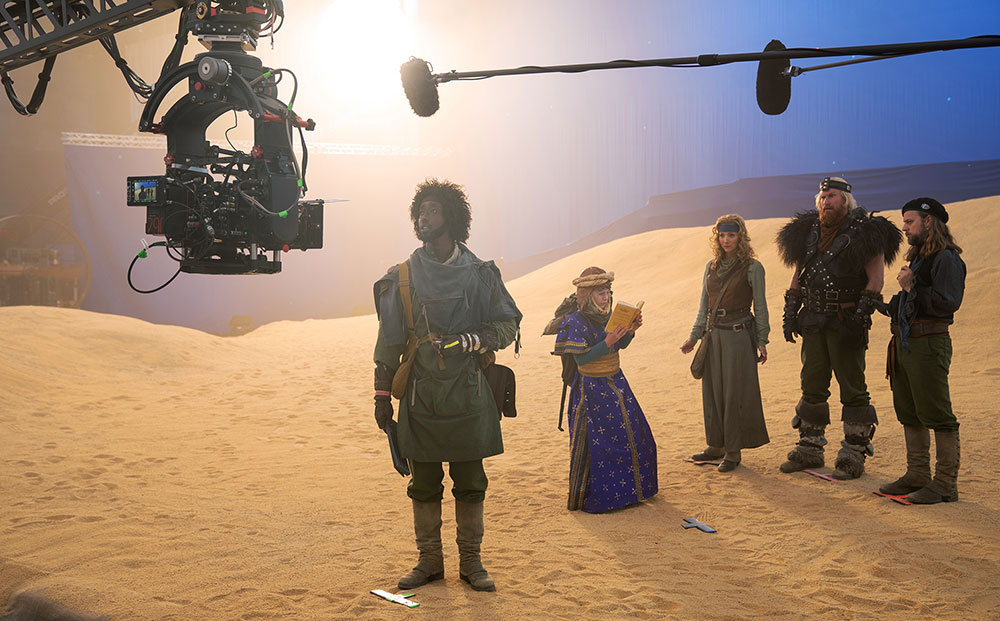

Digital Domain’s Phil Cramer talks about spending time at home with The Fantastic Four, creating a loveable superhuman baby, charming robot and rocky-but-vulnerable side to The Thing.

In The Fantastic Four: First Steps, Digital Domain had an opportunity to look at Marvel’s superheroes in a different way than as the familiar invincible individuals who flex their special powers to save the world. While those heroes often have a dark side, flaws or weaknesses that make them feel like people underneath the powerful exterior, in this film, we get to be at home with a dedicated group – a family bringing up a new baby.

Digital Domain worked on close to 400 shots seen in the final movie, featuring challenging digital characters in several different sequences set inside the home of Sue Storm, Reed Richards, Johnny Storm and Ben Grimm, aka The Thing, at the top of the Baxter Building in Manhattan. There, we see the Fantastic Four's everyday life as superheroes.

The artists’ main effort was devoted to The Thing, a complex asset shared between a group of VFX vendors, and eventually to the baby himself – Franklin. Because of the key roles they play in the story, a large part of the work was about making them believable and memorable. Digital Domain’s VFX Supervisor Phil Cramer (Jan Philip Cramer) talked about The Thing and about the kind of character Marvel wanted him to be.

“The Thing is a very vulnerable character,” Phil commented. “Once a good-looking pilot, he is now a pile of rocks, trying to adjust to his new life. Throughout the film, it becomes clear that he is not comfortable in his new skin. He attempts to hide behind his clothes, under a hat, and by growing a beard.” For Phil, recognisable human weaknesses are the best attributes for a CG character – no one loves a hero who is perfect in every way. Coping with those constant internal struggles is what makes The Thing feel real and alive.

Two Facial Systems

Due to his complexity, two facial systems were used for this character. One of these was FACS (Facial Action Coding System), with which Phil has considerable expertise. He said, “FACS is a common language to describe facial expressions triggered by muscle motion. Each muscle action is described in a FACS shape. To start, we needed to define a standard FACS set of expressions to be used by all VFX vendors. For Fantastic Four, I sat down with each company to determine what the best FACS set would be to cover every vendor’s facial solving and facial rig builds.

“Each FACS shape needs to be scanned in its extreme pose. We asked each actor to hold the pose for a second, and Tatiana Panek from Clear Angle Studios triggered a FACS facial scan using their Dorothy Rig. For one-to-one characters like Silver Surfer that keep the actor’s essential appearnce, it is critical to get highly accurate scans to ensure we match all their characteristics. For The Thing, we tried to artistically work the actor’s characteristics and nuances into his character’s facial expressions.”

The artists also decided to use Masquerade 3, Digital Domain’s proprietary facial animation system, which requires about 30 seconds of a specific type of training material – but does not rely on tracking markers. “For this, we capture a Facial range of motion (ROM), Expressive Lines and an Eye ROM. Here, the actor wears a helmet-mounted camera (HMC). We use this training data to understand the facial ranges for a given character, which we then apply to solve each shot,” Phil said.

“Our Facial Rigging Supervisor Rickey Cloudsdale, who headed up our Masquerade 3 development, defined these exact ROMs for the show, and then transferred all facial animation onto the defined FACS shapes and delivered them to each vendor.”

New Shared Masquerade 3 Pipeline

This team also developed a completely new Masquerade 3 pipeline for the 300 shots featuring The Thing. Notably, their new pipeline was successfully shared across four other vendors on the film, an uncommon achievement in the VFX industry.

It was a multiple step process. After the shoot, Digital Domain supplied all post-viz assembly scenes based on Xsens (used for full-body motion capture; see below) and Masquerade 3 data, cut to match timecode ranges that the client specified. “In essence, we did a layout pass for every select. We brought in the mocap, merged it with the facial capture and determined that it was in the correct world space location,” said Phil.

“This data would go to the postviz vendor and final vendors to use as their start point. We called this the assembly step under the supervision of our Mocap Supervisor, Connor Murphy. In all, Digital Domain set up over 1,160 assembly scene files that contained the character's body and face data to be used, ready for distribution to all vendors.”

Having such a unified approach resulted in consistency in character performance and quality across every shot, regardless of the studio executing it. The previs vendor, The Third Floor, also received raw dumps of the Masquerade3 data on the character rigs. As long takes aligned to timecode, without any offsetting for shot timecode, these raw facial solves allowed their previs artists some extra freedom.

From Previs to Postviz – Accelerated

This project has been the most extensive application of Masquerade 3 to date. It also proved crucial for the post-visualization team, which usually processes 10 to 15 times more data than the VFX team produces in the final stages. “The quality needs for postviz are much less, but the amount of actual data a postviz team deals with is a lot more,” said Phil.

“A finals vendor normally has around 300 to 600 shots, while postviz normally deals with upwards of 1,500 shots – at least. They feed directly into editorial, so turn-around speed is crucial. Every single VFX shot goes through the postviz vendor on a Marvel show, which means it feeds the entire production, rather than just one vendor’s work.”

Working solo, Rickey processed hours of data overnight from each vendor and the postviz team. The efficiency he achieved was remarkable. “Rickey is one of the brains behind Masquerade 3. Early on, Marvel had asked us about the feasibility of solving all facial data, rather than focusing on selected shots,” Phil said. “This seemed like a daunting task, as the amount to solve went up by 10x, so Rickey focused on automating the process, allowing it to be run via the command line.

“We would get daily deliveries of all facial data captured on a given day, and then auto-solve all clips in a directory structure and mimic that with animation files to be delivered to all the other vendors.” Such a feat would previously have required a huge team and weeks to accomplish, even for a single shot. Subsequently, a dedicated team was formed to process scene files, integrating body and facial data for seamless sharing with animators. Working through Masquerade3, Rickey processed approximately 60 hours of facial footage for three key characters – The Thing, Silver Surfer and Galactus.

Full-body Motion Capture

Digital Domain became the central hub for motion capture processes, including capturing the data, overseeing the facial and mocap prep for each character and, as described above, determining the precise FACS shapes.

The team used Xsens suits to capture the full-body motion. Early on, Digital Domain conducted numerous body action tests to gauge the desired motion and how it was translating from the mocap suit to the animation rig. Phil said, “Since Xsens data quality can vary depending on the environment in which it is captured, we needed to establish how quickly we could obtain the desired motions from the suit. Our Animation Supervisor Frankie Stellato and his animation team helped to define the motion and set the animation look for the character.

“We wanted to express how constantly aware he was of his larger body. For example, he would walk sideways through doors to avoid breaking them, step carefully down stairs, because they are not made for him, and feel heavy while in motion. His fingers were very limiting, of course, so we wanted to show the struggle and skill he has with his three fingers.”

The facial animation was a toned-down version of the actor, Ebon Moss-Bachrach. Here, they needed to prevent the cracks showing between the rocks of his face from becoming too distracting or deep. A lot of effort went into ensuring viewers understand where to focus on the face by modulating these gaps. Facial Lead Andrew Lema and the facial team continuously refined the facial expressions to ensure they conveyed the actor’s emotions as clearly as possible from the outset.

No Interference

Phil generally advises against imposing any restrictions on actors. Instead, he prefers to provide options for the actor to get into character. “Here, we tried different weight belts and limb weights. Initially, Ebon used these to get an understanding of the weight. Once this was understood, he used them less and less,” he said.

“You want to avoid having too many things interfering with the actor's motion, which would ‘bake’ the recorded performance into the motion. It's easier and more flexible to create these limitations in animation.

“We also had special gear for interactions. We built a prosthetic piece for his shoulders, arms and chest to allow for realistic live action-to-CG interactions, and used it in specific shots. Mocap Supervisor Connor Murphy helped define the use case with these and helped get Ebon comfortable wearing them.”

Clear Angle also captured full body scans of the actor and all his costumes. The costumes were made to match the Thing’s size and placed on a stand-in actor wearing a prosthetic suit. This allowed us to evaluate how the wrinkles should fall and how the materials behaved.

By the end, The Thing was quite a collaborative effort. As lead vendor, ILM built the initial model, while Digital Domain concentrated on facial shapes, initial design and created most of the costumes. Due to their focus on costumes, they ended up delivering the base body mesh, which turned out to be slimmer than the shirtless version of The Thing. Asset Supervisor Ron Miller then refined that asset so that it fit perfectly with the pipeline and costumes.

Beard Complexity

A significant and unusual challenge for The Thing involved the actor's beard, which had to be meticulously addressed during facial setup. While actors are typically required to remove facial hair for proper marker-based facial capture, where facial hair covers too much of the individual markers to get a decent facial solve, the Masquerade 3 software allowed Ebon to keep his beard without issue, overcoming conventional limitations.

Its markerless approach (described above) focusses on features, rather than tiny details, allowing artists to overcome this technical hurdle. Another training set with the beard must be captured to achieve this, but once recalibrated to a beard, the system runs identically.

“Coincidentally – not by design – The Thing also grows a beard as part of the story,” said Phil. “So, as well as the rest of the complexity, our artists faced the intricate task of simulating The Thing's developing stubble and beard. We ended up creating a complicated, rigid body simulation over a typical hair sim. We needed to keep the rocks from bending at any time and maintain their rigid look. It added a lot to his character, but we needed to ensure the core acting choices still came across cleanly to the audience.

Trouble with Babies

The Thing was an exciting project for the team, but as in real life, the baby threatened to steal the show. In order to create Franklin, Digital Domain artists were responsible for creating him both as a newborn baby and then as a slightly older one to account for the passage of time, adding up to a total of 150 shots, and designing several different outfits for the character as well. As the work unfolded, building Franklin was a whole new journey in itself.

“My role regarding Franklin was a little different than normal,” Phil said. “Initially, we used my own son, Cosmo Cramer, as a test baby and did all the needed scanning during an initial test shoot with our director, Matt Shackman. We wanted to best understand how to move forward with a baby.

“Having babies on set is challenging – they are nearly impossible to direct, bring many limitations regarding working hours and conditions, and then… babies grow. We knew we would have many stand-in babies and ended with around 30. It was our job to figure out how to make the results feel consistent, from shoot to post.

When the actual shoot started, I helped film 14 babies in different situations, met their parents, and helped Matt find the main baby to play Franklin. From there, I made sure we had all the data needed to pull this off.”

He spent over a month with the baby – actually a little girl called Ada Scott – and her mother every day to make sure they could achieve all the needed performance beats. Once again working with Clear Angle, a special baby-friendly scanning booth was designed and the baby scanned, under ideal lighting scenarios, over the course of two weeks at the beginning of the shoot.

Consistently Franklin

Because the desired age for the baby was so young, only about 4 months old and still developing – even when testing with Cosmo, Phil’s own son, the baby was just 8 months old – safety was his number one concern for the scanning booth. He said, “We designed a rig that can capture video and high-res images under controlled lighting, low enough to prevent damaging the baby's eyes, with a seat set up for a baby who can’t hold up his own head. This was also why we recorded over multiple weeks.

“We wanted to ensure the baby's look is consistent throughout the movie. When we initially meet Franklin on Earth, he is just days old. For this, we made a special Franklin that was based on those initial scans of Ada. We had a full groom, asset and matching training material for that baby.

“For later parts in the movie, she had grown too much, which meant growing our assets equally. We had to make an older version of the asset together with a new groom and matching training material.”

Digital Domain’s proprietary face-swapping tool Charlatan was used to explore ways to create the two versions of the same character. Using machine learning, Charlatan could be trained in the looks of the chosen baby, as well as relevant traits of an older baby, and used to generate a recognisable, natural-looking blend between them. Nevertheless, as useful as it was, Charlatan wasn’t going to be their magic answer. Compositing Lead Simon Richardson put considerable effort into management and development of the baby variants, but no single solution solved all shots.

HERBIE

Between young Franklin and The Thing, Digital Domain’s character building skills were heavily in demand for this film. But there was another member of the cast that brought the team back to something more familiar, a house robot called HERBIE.

“We love building and animating robots. In particular, our team has lots of experience with specialised robots, where form follows function,” commented Phil. “We understand how to create the necessary joints without changing the design. Our CG supervisor, Chi-Chang Chu, had just finished a huge robot project (The Electric State) at Digital Domain prior to Fantastic Four and brought a huge number of tips and tricks to keep HERBIE looking so real.”

According to the production brief, HERBIE is cute and trusting, with an almost child-like innocence. A big part of his character is his limitations. Phil agreed, “I always feel you want to embrace the design limitation, as that is what defines the character. HERBIE’s face has a very limited set of expressions, and his arms have only a limited range of motion, all of which add up to an adorable, yet real character.

“We handled most of the HERBIE shots on the film overall. As we built the character, we were involved in integrating the cassette face solution, establishing overall ranges of motion, and working out how he flies. A real-life prop was built for the character, with a tactile look and feel that we wanted to keep at all times. We also wanted to create motion that mimicked that live action prop, to keep him grounded in reality.”

Puppeteer

A puppeteer helped give HERBIE an on set presence the actors could interact with. The artists would then paint him out and replace the onset robot with their HERBIE. His performance served as some great inspiration, so that they often matchmoved the puppeteer’s overall body motion, and then layered further detail on top.

A sequence in which HERBIE spends time baby-proofing the housen was a lot of fun for the animation team. Each shot highlighted a different design element of HERBIE and really tested the limits of their animation puppet. Many shots have multiple panels to show the action from different angles, or show a repeated action in different locations.

“In this case, the puppeteer was present on set, focussing on the broad locomotions and allowing everyone to be aware of his presence. This was a crucial step. We would always base our ideas on what had been established in shot and just add to it. Having a character that was so real made HERBIE a huge joy to work with.

Visualising Invisibility

Digital Domain also helped with the distinctive effects that establish the identities of some of the other major characters. An example is the invisibility effect for Sue Storm, the Invisible Woman, resembling a beautiful animated lens aberration.

Phil said, “We tried to establish the look for Sue early on by using different styles for the test shots – one for her force field, one for invisibility and one for the baby scanning, or ultrasound. This approach was extremely helpful in finding the common ground between all her powers and using lens aberrations to visualise them. The idea was to show R G B getting pulled apart, that is, refracted into their own layers.”

The whole concept of the ultrasound visualisation was something Phil loved from the start. “Here, we needed to avoid it looking too medical and putting off a general audience. Our main goal was to keep it beautiful, almost ethereal. The baby itself was based on a scan of our Integration Supervisor’s baby when it was born. Our Compositing Look-dev artist Kym Olsen spearheaded the look of the X-Ray sequences as part of our early Sue Storm tests.

“The ultrasound process went exactly as planned following the initial test shot using a stunt actress. Once we applied the look directly to the shots, it fell quickly into place. Our FX team did an amazing job creating all the different layers that provided the final look. Lookdev Compositor Matt Brumit ran the majority of the shots, including the beautiful baby close-up.”

Human Torch

Digital Domain took control of Johnny Storm’s Human Torch fire effects when we see them around the Baxter Building as he flies in from outside and during a sequence when he glows within the dark lab. “Here, his flame needed to behave as realistically as possible,” said Phil. “We looked for different gas fire effects, but ended up keeping it pretty grounded in real fire.

“Our main focus was to show how the fire is formed on his body. The idea was that his body was emitting oxygen that erupts close to the surface into fire. This produced a small blue accent under the orange fire. Scott Stockdyk, the client-side VFX supervisor, had tried different chemicals affecting the gas fire to simulate this. In the end, we produced a very subtle version of that fire.” digitaldomain.com

Words: Adriene Hurst, Editor